-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ayse Cetinkaya, Mohamed Zeriouh, Oliver-Joannis Liakopoulos, Stefan Hein, Tamor Siemons, Peter Bramlage, Markus Schönburg, Yeong-Hoon Choi, Manfred Richter, Pulmonary herniation after minimally invasive cardiac surgery: review and implications from a series of 20 cases, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 11, November 2020, rjaa415, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa415

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Minimally invasive cardiac surgery (MICS) via right lateral mini thoracotomy is the gold standard treatment approach for mitral and tricuspid valve disorders. Other selected procedures (e.g. transapical aortic valve implantation, MIDCAB) require a left lateral mini thoracotomy for surgical access. Advantages of MICS over complete sternotomy are well known, but access-related complications post MICS, such as pulmonary herniation, are often underestimated/overlooked. In males, a pulmonary herniation in the proximity of the former thoracotomy is often clinically visible, especially when the intrathoracic pressure rises (e.g. during coughing). In females, clinical symptoms may be hidden by the breast and patients often have unspecific complaints or occasional pain when coughing, making identification of a lung herniation more difficult. Chest computed tomography is the diagnostic tool of choice for pulmonary herniations. Using a series of 20 patients with pulmonary herniation post MICS, we report our findings in diagnosis and treatment of this condition.

INTRODUCTION

Minimally invasive cardiac surgery (MICS) was introduced in the mid-1990s to repair mitral valves [1]. Nowadays, the standard approach for treating mitral and tricuspid valve diseases is right lateral mini thoracotomy. The advantages of MICS over complete sternotomy are well established and include a reduced complication rate associated with wound healing disorders [2]. The complications associated with MICS, however, are poorly described in the literature. Pulmonary herniation is a typical complication after MICS that is often misinterpreted.

The symptoms of pulmonary herniation present differently in male and female patients. In men, patients with pulmonary hernia complain of visible right thoracic herniation when coughing, which can occur several months after the primary operation. Female patients with pulmonary hernia, on the other hand, describe unspecific complaints and occasionally experience unspecific pain. Clinical examination and diagnosis in female patients, however, is more difficult because the typical site of herniation is hidden by the breast. Publication of a handful of case reports indicate that pulmonary hernias can be corrected with surgical intervention [3–5]. Here we report on a series of 20 patients with pulmonary hernias observed as a subset of 1381 minimally invasive operations performed over a 7-year period (Table 1). This study was approved by the local ethic committee (Nr.: EF 156/2014).

Characteristics of the 20 patients with pulmonary herniation after MICS (2016–2019)

| Patient . | Gender . | Age . | BMI . | Adipositas . | COPD . | Primary operation (MIS) . | Date of primary operation . | Time of CT chest/WA . | Sym LH . | CWRec . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 62 | 27.2 | Yes | Yes | MVR | January 2016 | CT January 2016 | No | No |

| 2 | Male | 47 | 26.8 | No | No | MVR | January 2016 | Unknown | Yes | February 2016 |

| 3 | Male | 62 | 30.9 | Yes | No | MVR | January 2016 | CT October 2018 | Yes | November 2018 |

| 4 | Female | 63 | 22.4 | No | No | MVR | February 2016 | WA December 2016 | No | No |

| 5 | Male | 73 | 28.1 | Yes | Yes | MVRep | January 2017 | WA June 17 | No | No |

| 6 | Male | 74 | 30.0 | Yes | No | MVR | January 2017 | CT March 2017 | No | No |

| 7 | Female | 60 | 22.8 | No | No | MVRep | February 2017 | OP February 2017 | Yes | February 2017 |

| 8 | Male | 69 | 22.8 | No | No | MVR | March 2017 | WA December 2017 | No | No |

| 9 | Male | 58 | 28.4 | Yes | No | MVR | March 2017 | WA March 2018 | Yes | March 2017 |

| 10 | Female | 81 | 37.5 | Yes | No | MVRep | June 2017 | CT June 2017 | Yes | No* |

| 11 | Male | 58 | 24.0 | Yes | No | MVR | July 2017 | CT July 2017 | Yes | August 2017 |

| 12 | Male | 78 | 25.2 | No | Yes | MVR | July 2017 | CT July 2017 | No | No |

| 13 | Male | 70 | 27.1 | Yes | No | MVR | September 2017 | CT August 2018 | Yes | September 2018 |

| 14 | Male | 63 | 30.2 | Yes | No | MVR | November 2017 | CT May 2018 | Yes | May 2018 |

| 15 | Male | 70 | 28.7 | Yes | No | MVR | December 2017 | CT January 2018 | Yes | January 2018 |

| 16 | Male | 55 | 31.7 | Yes | No | MVR | January 2018 | CT June 2018 | Yes | June 2018 |

| 17 | Male | 54 | 22.4 | No | No | MVR | February 2018 | CT June 2019 | Yes | June 2019 |

| 18 | Male | 37 | 26.8 | No | No | ASDc | September 2018 | CT September 2018 | Yes | September 2019 |

| 19 | Female | 49 | 27.2 | Yes | No | MVRep | April 2019 | CT April 2019 | Yes | April 2019 |

| 20 | Female | 61 | 19.0 | No | No | MVR | April 2019 | CT April 2019 | No | No |

| Patient . | Gender . | Age . | BMI . | Adipositas . | COPD . | Primary operation (MIS) . | Date of primary operation . | Time of CT chest/WA . | Sym LH . | CWRec . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 62 | 27.2 | Yes | Yes | MVR | January 2016 | CT January 2016 | No | No |

| 2 | Male | 47 | 26.8 | No | No | MVR | January 2016 | Unknown | Yes | February 2016 |

| 3 | Male | 62 | 30.9 | Yes | No | MVR | January 2016 | CT October 2018 | Yes | November 2018 |

| 4 | Female | 63 | 22.4 | No | No | MVR | February 2016 | WA December 2016 | No | No |

| 5 | Male | 73 | 28.1 | Yes | Yes | MVRep | January 2017 | WA June 17 | No | No |

| 6 | Male | 74 | 30.0 | Yes | No | MVR | January 2017 | CT March 2017 | No | No |

| 7 | Female | 60 | 22.8 | No | No | MVRep | February 2017 | OP February 2017 | Yes | February 2017 |

| 8 | Male | 69 | 22.8 | No | No | MVR | March 2017 | WA December 2017 | No | No |

| 9 | Male | 58 | 28.4 | Yes | No | MVR | March 2017 | WA March 2018 | Yes | March 2017 |

| 10 | Female | 81 | 37.5 | Yes | No | MVRep | June 2017 | CT June 2017 | Yes | No* |

| 11 | Male | 58 | 24.0 | Yes | No | MVR | July 2017 | CT July 2017 | Yes | August 2017 |

| 12 | Male | 78 | 25.2 | No | Yes | MVR | July 2017 | CT July 2017 | No | No |

| 13 | Male | 70 | 27.1 | Yes | No | MVR | September 2017 | CT August 2018 | Yes | September 2018 |

| 14 | Male | 63 | 30.2 | Yes | No | MVR | November 2017 | CT May 2018 | Yes | May 2018 |

| 15 | Male | 70 | 28.7 | Yes | No | MVR | December 2017 | CT January 2018 | Yes | January 2018 |

| 16 | Male | 55 | 31.7 | Yes | No | MVR | January 2018 | CT June 2018 | Yes | June 2018 |

| 17 | Male | 54 | 22.4 | No | No | MVR | February 2018 | CT June 2019 | Yes | June 2019 |

| 18 | Male | 37 | 26.8 | No | No | ASDc | September 2018 | CT September 2018 | Yes | September 2019 |

| 19 | Female | 49 | 27.2 | Yes | No | MVRep | April 2019 | CT April 2019 | Yes | April 2019 |

| 20 | Female | 61 | 19.0 | No | No | MVR | April 2019 | CT April 2019 | No | No |

Legend: *No, patient refuses surgery. ASDc, atrial septal defect closure; CWRec, chest wall reconstruction; MVR, mitral valve repair; MVRep, mitral valve replacement; sym LH, symptomatic lung hernia; WA, wound ambulance.

Characteristics of the 20 patients with pulmonary herniation after MICS (2016–2019)

| Patient . | Gender . | Age . | BMI . | Adipositas . | COPD . | Primary operation (MIS) . | Date of primary operation . | Time of CT chest/WA . | Sym LH . | CWRec . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 62 | 27.2 | Yes | Yes | MVR | January 2016 | CT January 2016 | No | No |

| 2 | Male | 47 | 26.8 | No | No | MVR | January 2016 | Unknown | Yes | February 2016 |

| 3 | Male | 62 | 30.9 | Yes | No | MVR | January 2016 | CT October 2018 | Yes | November 2018 |

| 4 | Female | 63 | 22.4 | No | No | MVR | February 2016 | WA December 2016 | No | No |

| 5 | Male | 73 | 28.1 | Yes | Yes | MVRep | January 2017 | WA June 17 | No | No |

| 6 | Male | 74 | 30.0 | Yes | No | MVR | January 2017 | CT March 2017 | No | No |

| 7 | Female | 60 | 22.8 | No | No | MVRep | February 2017 | OP February 2017 | Yes | February 2017 |

| 8 | Male | 69 | 22.8 | No | No | MVR | March 2017 | WA December 2017 | No | No |

| 9 | Male | 58 | 28.4 | Yes | No | MVR | March 2017 | WA March 2018 | Yes | March 2017 |

| 10 | Female | 81 | 37.5 | Yes | No | MVRep | June 2017 | CT June 2017 | Yes | No* |

| 11 | Male | 58 | 24.0 | Yes | No | MVR | July 2017 | CT July 2017 | Yes | August 2017 |

| 12 | Male | 78 | 25.2 | No | Yes | MVR | July 2017 | CT July 2017 | No | No |

| 13 | Male | 70 | 27.1 | Yes | No | MVR | September 2017 | CT August 2018 | Yes | September 2018 |

| 14 | Male | 63 | 30.2 | Yes | No | MVR | November 2017 | CT May 2018 | Yes | May 2018 |

| 15 | Male | 70 | 28.7 | Yes | No | MVR | December 2017 | CT January 2018 | Yes | January 2018 |

| 16 | Male | 55 | 31.7 | Yes | No | MVR | January 2018 | CT June 2018 | Yes | June 2018 |

| 17 | Male | 54 | 22.4 | No | No | MVR | February 2018 | CT June 2019 | Yes | June 2019 |

| 18 | Male | 37 | 26.8 | No | No | ASDc | September 2018 | CT September 2018 | Yes | September 2019 |

| 19 | Female | 49 | 27.2 | Yes | No | MVRep | April 2019 | CT April 2019 | Yes | April 2019 |

| 20 | Female | 61 | 19.0 | No | No | MVR | April 2019 | CT April 2019 | No | No |

| Patient . | Gender . | Age . | BMI . | Adipositas . | COPD . | Primary operation (MIS) . | Date of primary operation . | Time of CT chest/WA . | Sym LH . | CWRec . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 62 | 27.2 | Yes | Yes | MVR | January 2016 | CT January 2016 | No | No |

| 2 | Male | 47 | 26.8 | No | No | MVR | January 2016 | Unknown | Yes | February 2016 |

| 3 | Male | 62 | 30.9 | Yes | No | MVR | January 2016 | CT October 2018 | Yes | November 2018 |

| 4 | Female | 63 | 22.4 | No | No | MVR | February 2016 | WA December 2016 | No | No |

| 5 | Male | 73 | 28.1 | Yes | Yes | MVRep | January 2017 | WA June 17 | No | No |

| 6 | Male | 74 | 30.0 | Yes | No | MVR | January 2017 | CT March 2017 | No | No |

| 7 | Female | 60 | 22.8 | No | No | MVRep | February 2017 | OP February 2017 | Yes | February 2017 |

| 8 | Male | 69 | 22.8 | No | No | MVR | March 2017 | WA December 2017 | No | No |

| 9 | Male | 58 | 28.4 | Yes | No | MVR | March 2017 | WA March 2018 | Yes | March 2017 |

| 10 | Female | 81 | 37.5 | Yes | No | MVRep | June 2017 | CT June 2017 | Yes | No* |

| 11 | Male | 58 | 24.0 | Yes | No | MVR | July 2017 | CT July 2017 | Yes | August 2017 |

| 12 | Male | 78 | 25.2 | No | Yes | MVR | July 2017 | CT July 2017 | No | No |

| 13 | Male | 70 | 27.1 | Yes | No | MVR | September 2017 | CT August 2018 | Yes | September 2018 |

| 14 | Male | 63 | 30.2 | Yes | No | MVR | November 2017 | CT May 2018 | Yes | May 2018 |

| 15 | Male | 70 | 28.7 | Yes | No | MVR | December 2017 | CT January 2018 | Yes | January 2018 |

| 16 | Male | 55 | 31.7 | Yes | No | MVR | January 2018 | CT June 2018 | Yes | June 2018 |

| 17 | Male | 54 | 22.4 | No | No | MVR | February 2018 | CT June 2019 | Yes | June 2019 |

| 18 | Male | 37 | 26.8 | No | No | ASDc | September 2018 | CT September 2018 | Yes | September 2019 |

| 19 | Female | 49 | 27.2 | Yes | No | MVRep | April 2019 | CT April 2019 | Yes | April 2019 |

| 20 | Female | 61 | 19.0 | No | No | MVR | April 2019 | CT April 2019 | No | No |

Legend: *No, patient refuses surgery. ASDc, atrial septal defect closure; CWRec, chest wall reconstruction; MVR, mitral valve repair; MVRep, mitral valve replacement; sym LH, symptomatic lung hernia; WA, wound ambulance.

CASE SERIES REPORT

Diagnosis of lung hernias

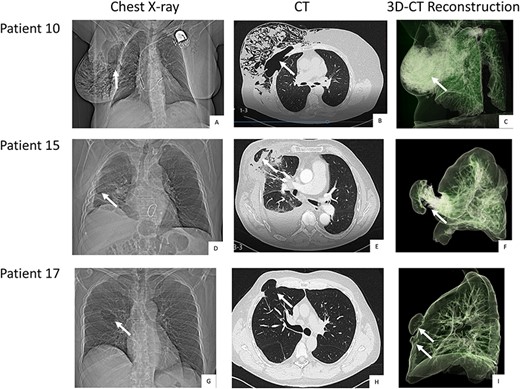

The initial diagnostic step of lung herniation involves clinical examination of the patient and palpation while coughing to identify herniation on the right thoracic wall. Further diagnostic measures include a chest X-ray and thoracic computed tomography (CT) scan, with the latter being the diagnostic tool of choice. Thoracic CT should be performed in women with unspecific symptoms either to exclude or provide evidence of lung herniation. Even if a protrusion in the area of the chest wall is observed during coughing, a thoracic CT is essential for diagnosis and for surgical planning. CT scans help to identify the exact area where chest wall reconstruction is necessary and to detect or exclude the presence of a double pulmonary hernia involving two intercostal spaces (Fig. 1).

Pre-operative chest-X-ray, CT and thoracic CT reconstruction of patient 10 (A, B, C), 15 (D, E, F) and 17 (G, H, I). Legend: The white arrows point at the herniation. Patient 10 and 15 come with a single hernia. Patient 17 was diagnosed with double herniation.

Only a few patients are symptomatic shortly after the MICS procedure. A protrusion on the right thoracic side that is visible when coughing often first presents in the months following the primary operation. This symptom is easier to diagnose in male patients than in female patients. Patient complaints regarding respiratory pain and discomfort post MICS should be taken seriously and followed up with a chest CT (Fig. 1).

A pulmonary hernia results in constriction of the lungs at the level of the intercostal space and protrusion into the subcutaneous tissue outside the thoracic plain. Lung tissue is elastic and its extension is anatomically limited by the thoracic wall. If the integrity of the thoracic wall is compromised by an intercostal space, the lung trends to herniate through this lesion. The subcutis tissue gives only limited resistance to lung extension, so the pulmonary hernia tends to become larger over time.

It is essential that a right thoracic tumour or protrusion after MICS is not punctured for diagnosis as this would result in an iatrogenic pneumothorax. Patients with symptomatic pulmonary hernias should be treated with surgical chest wall reconstruction using autologous material.

Surgical care of the lung hernia by chest wall reconstruction with autologous tissue

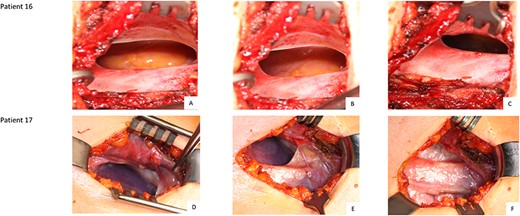

Surgical correction of the pulmonary hernia is usually carried out using the pre-existing scar below the right nipple as surgical access site. However, if chest CT and clinical examination show the pulmonary hernia to be superior to the original access site, then a new skin incision above the existing incision may be necessary for better access to the hernia (Fig. 2, patient 3 + 17). Careful preparation of the subcutis and presentation of the hernial cavity should be carried out to avoid injury of the lungs. The extrathoracic hernial cavity, as a continuation or expansion of the parietal pleura, is covered with an epithelialized layer. The pulmonary hernia should be inspected under ventilation (Fig. 2, patient 16 + 17). If the chest CT reveals a double lung hernia then a targeted search for a second pulmonary hernia in the adjacent intercostal space should be performed (Fig. 2, patient 16 + 17).

Intraoperative finding of patients 16 (A, B, C) and 17 (D, E, F): cavity of an extrathoracic epithelialized hernia Legend: Patient 16 has a single hernia. Patient 17 was diagnosed with double herniation.

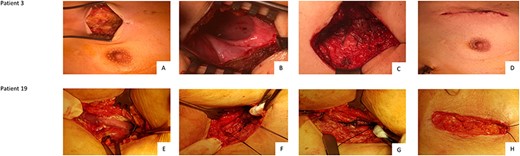

After inspection of the hernia, the epithelialized lining of the hernial cavity is prepared and dissected down to the rib level. The excess tissue is then reduced leaving an ~1.5 cm wide margin to facilitate breast wall reconstruction with autologous tissue. Following excision of the excess tissue, a thoracic drainage should be placed two intercostal spaces below the site of lung herniation. After that, 2–3 rib adaptation sutures should be placed without knotting. To adapt the parietal pleura, the epithelialized layer is closed using a continuous suture at the level of the intrathoracic site of the ribs. The previously placed rib adaptation sutures are then knotted followed by typical adaptation of the muscle layer. The double lumen ventilation is then initiated. By inflating the lungs further hernial gaps are excluded and a lung atelectasis is avoided. This is followed by adaptation of the subcutis and skin with continuous suture. At the end of the operation a sterile wound dressing is applied (Fig. 3, patient 3 + 19).

Chest wall reconstruction in Patient 3 (A, B, C, D) and Patient 19 (E, F, G, H) Legend: Patient 3: A: Opening of the skin. Hernia may be located substantially higher than the original skin incision; B: Display and opening of the epithelialized cavity. Preparation and excision; C: After thoracic drainage and 2–3 rib adapting sutures, the muscle is adapted; D: Closure of the subcutis followed by skin suture. Patient 19: E: Opening of the skin at the original incision. F: Placement of two rib adapting sutures after insertion of chest tubes. G: Continuous muscle adaption; H: Closure of the subcutis followed by skin suture.

The patient should be extubated in the operating room and then transferred to the regular ward. A post-operative chest X-ray should be performed to exclude pneumothorax and/or haemothorax. The thoracic drainage can be removed on the first post-operative day, allowing the patient to be discharged home. It is recommended that the patient wears a chest strap for ~2–3 weeks after the surgical procedure.

The long-term examination of these patients showed no evidence of a recurrent pulmonary hernia after breast wall reconstruction with autologous tissue.

DISCUSSION

Lung herniation is usually classified by location (cervical, thoracic or diaphragmatic) and cause (either congenital or acquired, the latter can be further subdivided into traumatic, spontaneous or pathologic) [6]. For the majority of patients, pulmonary hernias are the result of either trauma (e.g. a car accident) or thoracic surgery. Pulmonary hernias after minimally invasive thoracotomies are observed relatively frequently. The clinical diagnosis of pulmonary herniation is often overlooked, especially in female patients who do not present with classical chest wall protrusion when coughing, but complain of unspecific symptoms or pain when coughing. With this in mind, pulmonary hernias should be considered in the evaluation of any persistent pain and/or swelling and/or unspecific complaints when coughing in patients after MICS. Our findings support previous case reports which suggest that, in these patients, a chest CT is the diagnostic tool of choice to display or exclude a pulmonary hernia or double pulmonary hernia [7]. After diagnosis, corrective surgery is the preferred treatment option for a pulmonary hernia post MICS. A breast wall reconstruction with autologous material can easily be carried out and is therapy of choice.

CONCLUSIONS

- (1)

MICS is an appropriate approach to avoid the complications of a sternotomy. However, meticulous closing of the lateral mini thoracotomy is mandatory to prevent lung herniation.

- (2)

Relevant lung herniation is possible in very small skin incisions (3–4 cm); the incision in the intercostal space for an MICS procedure is usually ~ 5–7 cm incision wide.

- (3)

Lung herniation after a lateral mini thoracotomy is observed relatively frequently and often not recognized early on (especially in female patients). In case of unspecific chest complaints, a diagnostic work-up to detect lung herniation is recommended.

- (4)

Beyond the initial clinical examination (palpation of a ‘balloon’ on the chest when coughing), a CT chest is considered the gold standard.

- (5)

Double pulmonary herniation may occur; it is not uncommon during the primary intervention to select a too-deep intercostal space to access the heart, which has to be corrected by choosing the intercostal space above.

- (6)

A chest wall reconstruction is required in the case of pulmonary herniation and can be performed with autologous material in the majority of cases.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.

References

- surgical procedures, minimally invasive

- cardiac surgery procedures

- lung

- cough

- hernias

- pain

- surgical procedures, operative

- thoracotomy

- breast

- diagnosis

- lung hernias

- clinical diagnostic instrument

- disorders of both mitral and tricuspid valves

- chest ct

- gold standard

- malnutrition-inflammation-cachexia syndrome

- total sternotomy