-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Joel M Prince, Ji Fan, Subhasis Misra, Clinical suspicion is key: an unusual presentation of septic arthritis after distal pancreatectomy, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 6, June 2019, rjz203, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjz203

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Septic arthritis is the result of an infectious agent gaining access a sterile joint. This results in a devastating inflammatory response that leads to rapid destruction of intra-articular cartilage and with it significant morbidity. This case study reports an unusual presentation of septic arthritis following abdominal surgery; specifically, a distal pancreatectomy performed for an enlarged, mid-body pancreas mass involving the splenic artery. This is the first reported case of septic arthritis following abdominal surgery, though the exact etiology is unknown.

INTRODUCTION

Septic arthritis is the result of an infectious agent gaining access to a joint resulting in joint inflammation. Due to the major morbidity associated with the ensuing rapid intra-articular cartilage destruction, this condition is considered a surgical emergency when diagnosed. The three classic etiologies for this joint infection are direct inoculation, spread from contiguous infected tissues, and hematogenous seeding [1].

CASE REPORT

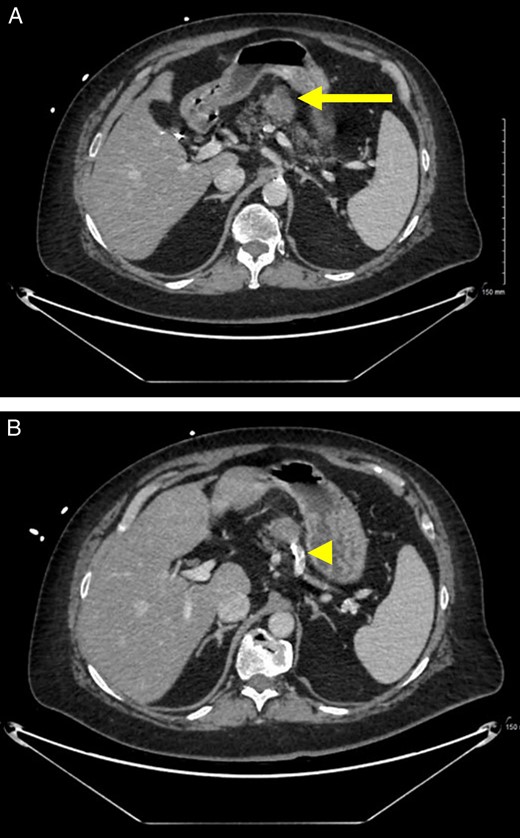

A 60-year-old woman with underlying hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus on insulin, gastroparesis, sinoatrial block status post cardiac pacemaker, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and prior transient ischemic attack presented with hypertensive urgency, nausea, vomiting and left subcostal pain radiating posteriorly. The surgical oncology service was consulted when a CT scan revealed a pancreatic mass that had enlarged from imaging obtained eight years prior. More concerningly, this 3.4 cm, mid-body pancreatic mass now involved the splenic artery (Fig. 1). The patient recalled two previous endoscopic biopsies of the mass were non-diagnostic. Of note, she had an extensive past surgical history: cholecystectomy, congenital umbilical hernia repair, hysterectomy, and several bilateral knee surgeries which included patellar tendon repair, ACL repair, and meniscal repair.

Preoperative imaging. (A) CT scan with IV contrast demonstrates a lobulated, heterogeneous, exophytic, enhancing mass (arrow) in the mid-body of the pancreas. (B) There is abutment of a calcified splenic artery (arrowhead).

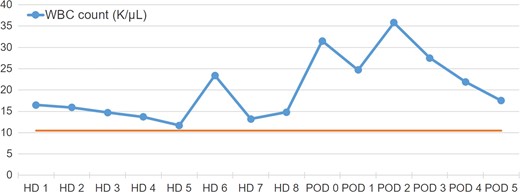

Due to persistent vomiting, an EGD was performed demonstrating mild gastritis and a small hiatal hernia. Pyloric botox injection was performed for presumed concomitant gastroparesis, and subsequent gastric emptying study demonstrated rapid emptying. Initially, the patient had an asymptomatic leukocytosis that mirrored the severity of her nausea and vomiting, ranging 11.7 K/μL to 23.1 K/μL (Fig. 2). Dehydration did not seem to explain her leukocytosis as her serum creatinine ranged from 0.7 to 0.9 mg/dL and blood urea nitrogen was only mildy elevated at 11–34 mg/dl during this time. Her nausea and vomiting remained related to oral consumption. She denied any recent exposure to sick contacts, risky behaviors including intravenous drug use, recent history of falls or knee injury, and never complained of arthralgias. Empirically ceftriaxone was started as further workup of this persistent leukocytosis was suggestive of an UTI. Blood cultures drawn had no growth.

White blood cell trend during hospitalization. The patient had an elevated WBC prior to surgery and was found to have an UTI. On postoperative Day 2, her WBC increased to 35.8 K/μL.

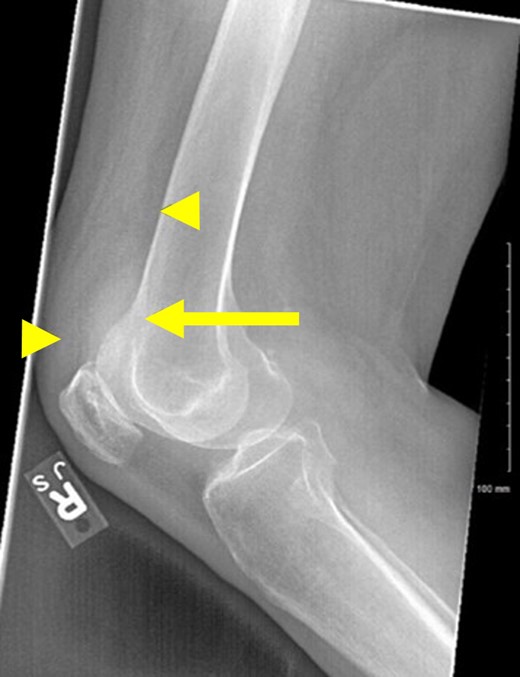

The patient’s leukocytosis improved to 14.8 K/μL but did not completely normalize prior to her undergoing an open distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy (Figs 2 and 3). The surgery was uncomplicated, and her initial recovery was as expected. On postoperative day two, she began complaining of bilateral knee pain, right worse than left. She was mildly tachycardic with a rising leukocytosis to 35.8 K/μL which had previously downtrended postoperatively (Fig. 2). Her right knee was warm, swollen, and had restricted extension. Radiographs demonstrated an effusion (Fig. 4). An urgent consult to orthopedic surgery was called. Arthrocentesis was performed which revealed grossly turbid synovial fluid with 86 350 WBCs/mm3 consistent with septic arthritis (Table 1).

Gross pathology. A complex, heterogeneous mass with cystic component is seen in the body of the pancreas.

Right lateral knee radiograph. The joint effusion (arrow) can be most clearly visualized between normal anterior anatomic fat pads, the quadriceps and prefemoral (arrowheads).

Synovial fluid analysis. Fluid from joint aspiration is suspicious for septic arthritis despite there being no organisms seen on gram stain.

| Characteristic . | Description . |

|---|---|

| Appearance | Turbid |

| White blood cells | 86 350 cells/mm3 |

| Red blood cells | 10 000 cells/mm3 |

| Polynuclear cells | 98% |

| Lymphocytes | 2% |

| Gram stain | No organisms |

| Crystals | No crystals seen |

| Characteristic . | Description . |

|---|---|

| Appearance | Turbid |

| White blood cells | 86 350 cells/mm3 |

| Red blood cells | 10 000 cells/mm3 |

| Polynuclear cells | 98% |

| Lymphocytes | 2% |

| Gram stain | No organisms |

| Crystals | No crystals seen |

Synovial fluid analysis. Fluid from joint aspiration is suspicious for septic arthritis despite there being no organisms seen on gram stain.

| Characteristic . | Description . |

|---|---|

| Appearance | Turbid |

| White blood cells | 86 350 cells/mm3 |

| Red blood cells | 10 000 cells/mm3 |

| Polynuclear cells | 98% |

| Lymphocytes | 2% |

| Gram stain | No organisms |

| Crystals | No crystals seen |

| Characteristic . | Description . |

|---|---|

| Appearance | Turbid |

| White blood cells | 86 350 cells/mm3 |

| Red blood cells | 10 000 cells/mm3 |

| Polynuclear cells | 98% |

| Lymphocytes | 2% |

| Gram stain | No organisms |

| Crystals | No crystals seen |

Broad spectrum antibiotics were initiated prior to urgent arthrotomy with irrigation and debridement of her right knee joint. Following this intervention, her signs of infection subsequently resolved, and the patient’s recovery was otherwise uneventful. Paradoxically, gram stain, crystal analysis, and culture of the synovial aspirate were all negative (Table 1). Final pathology revealed a microcystic serous cystadenoma with negative margins. She was discharged on a four-week course of intravenous antibiotics and 2 weeks of rivaroxaban.

DISCUSSION

Septic arthritis has been previously reported secondary to retroperitoneal abscess, sternal surgical wound infection, perforation of abdominal organs, and colonic adenocarcinoma [2–5]. This case is unique as it is the first case of septic arthritis reported after an abdominal surgery.

Monoarthritis was unexpected in this patient lacking classic risk factors such as evidence of bacteremia, intravenous drug use, recent joint trauma, and history of gout. The exact source of septic arthritis in this patient remains unknown, but possibilities include a perioperative transient bacteremia or an indolent infection that was subclinical preoperatively. Despite this, she did have several risk factors. There is a higher incidence and poorer outcomes for septic arthritis in patients with underlying joint disorders or prostheses [6, 7]. While this patient had bilateral native knees, she did have several previous knee operations which may have increased her risk for septic arthritis. Diabetes is another known risk factor for this infection [7]. Initially upon admission, her blood glucose was recorded in the high 300 s. Postoperatively, it was somewhat better controlled ranging from 120 to 260 mg/dl.

Typically, a WBC > 50,000 on arthrocentesis is highly suggestive of septic arthritis [8]. However, 12.5% of patients with gout, 10% with pseudogout, and 4% with rheumatoid arthritis will have cell counts as high [8]. To confirm the diagnosis, other analyses such as turbidity and percentage of polynuclear cells should be taken into account. In this patient with no history of inflammatory arthropathies, the joint fluid was turbid with a 98% neutrophil predominance and had an absence of crystals (Table 1), further supporting the diagnosis of septic arthritis.

Immediate intravenous antibiotic therapy and rapid irrigation and drainage of the joint is imperative if the diagnosis is suspected. A negative Gram stain is unreliable for decision making as sensitivities of 29–50% have been reported [2, 9], especially in the setting of recent antibiotic therapy. Also synovial fluid culture sensitivity may only be as high as 76% [8]. Given this, the negative culture in this patient who was on concurrent antibiotics at the time of aspiration for a preoperative UTI is not unexpected. Normally antibiotic coverage for S. aureus and streptococci is required as these are the most common isolates; however, in this patient, gram-negative coverage was also necessary given her recent abdominal surgery [7].

A few cases of septic arthritis have been reported in patients presenting with intra-abdominal abscesses, primary retroperitoneal abscess and secondary abscess from abdominal viscus perforation [3, 5], but not after abdominal surgery. This case illustrates the importance of considering septic arthritis when evaluating any monoarthropathy, even in patients without obvious risk factors. Once suspicion of the diagnosis is confirmed with arthrocentesis, urgent operative irrigation and debridement are necessary.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None to declare.

DISCLAIMER

This research was supported (in whole or in part) by HCA Healthcare and/or an HCA Healthcare affiliated entity. The views expressed in this publication represent those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of HCA Healthcare or any of its affiliated entities.