-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Masakazu Ohuchi, Noriyuki Inaki, Kunihiko Nagakari, Shintaro Kohama, Kazuhiro Sakamoto, Yoichi Ishizaki, Transabdominal preperitoneal repair using barbed sutures for bilateral inguinal hernia in liver cirrhosis with ascites, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 6, June 2019, rjz199, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjz199

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The appropriate surgical treatment for inguinal hernia in patients with liver cirrhosis and ascites remains controversial. A 79-year-old male undergoing treatment for Child–Pugh B hepatitis C-induced liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma complicated with bilateral inguinal hernia underwent transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) repair. During surgery, barbed sutures were used to facilitate appropriate peritoneal closure. His postoperative course was uneventful. Information on TAPP repair for inguinal hernia in patients with liver cirrhosis and ascites is limited. The International Guidelines for Inguinal Hernia Management recommend Lichtenstein repair for patients with ascites. TAPP repair requires peritonectomy via a posterior endoscopic approach; therefore, proper peritoneal closure is important to prevent the leakage of ascitic fluid. Herein, TAPP repair was safely and successfully completed using barbed sutures to achieve proper and strong peritoneal closure. TAPP repair using barbed sutures can be an effective treatment option for patients with liver cirrhosis and ascites.

HIGHLIGHTS

Inguinal hernia treatment in liver cirrhosis patients with ascites is controversial.

Inguinal hernia patients with ascites are recommended to undergo Lichtenstein repair.

A Child–Pugh B cirrhosis patient with ascites underwent TAPP repair.

Accurate peritoneal closure by barbed sutures makes TAPP a viable treatment option.

INTRODUCTION

During surgical planning for inguinal hernia in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis accompanied by ascites, exacerbation of liver cirrhosis, risk of postoperative wound infection, recurrence of hernia, and ascitic leakage should be thoroughly considered. Several reports have recommended the safety and effectiveness of open procedures for inguinal hernia repair in patients with liver cirrhosis accompanied by ascites [1, 2]. The International guidelines for groin hernia management indicate that treatment of patients with ascites is complicated and have recommended the use of Lichtenstein repair technique [3].

We describe a case wherein TAPP repair was safely and successfully performed using barbed sutures in a patient with Child–Pugh B liver cirrhosis with ascites.

CASE REPORT

The patient was a 79-year-old male undergoing treatment for hepatitis C-induced liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver functional reserve was assessed to be Child–Pugh B based on total bilirubin level of 1.3 mg/dl, albumin level of 2.9 g/dl, prothrombin time activity of 70.7%, and presence of moderate ascites. His prognosis was suspected to be of approximately 1 year.

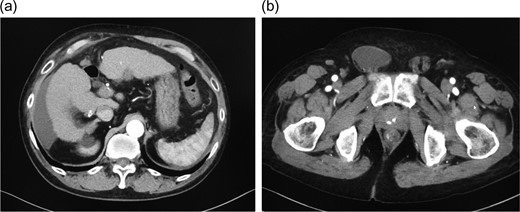

One month before the visit, he noticed swelling in the right inguinal area and mild, palpable swelling on the left area. Abdominal computed tomography revealed the presence of moderate ascites with right inguinal hernia (Fig. 1a and b). He was symptomatic and opted for surgery. Based on preoperative assessments, hernia repair under general anesthesia was considered and TAPP repair was performed.

a) Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography shows moderate ascites in the abdominal cavity. (b) Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography shows an indirect hernia in the right inguinal area, with inflow of ascites into the hernia sac.

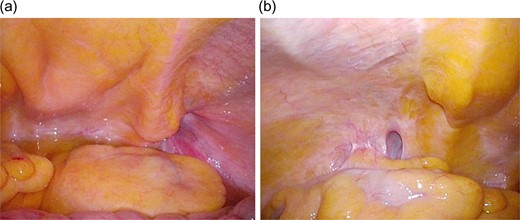

Intraabdominal examination revealed bilateral indirect inguinal hernias (Fig. 2a and b) with moderate ascites that extended from the pouch of Douglas to lower abdomen. We performed laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair using the same extent of dissection and dissection plane as used for normal cases, that is, those without ascites.

(a) On intraoperative laparoscopic view, right-sided indirect inguinal hernia and ascites in the pouch of Douglas are seen. (b) On intraoperative laparoscopic view, left-sided indirect inguinal hernia is seen.

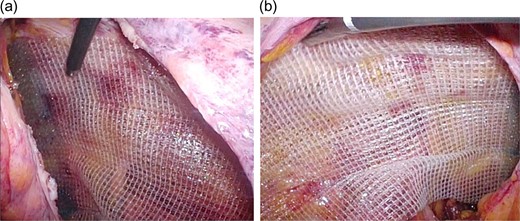

We used a 15- × -10-cm2 self-fixating mesh (ProGripTM) on the right side and 13- × 9-cm2 mesh on the left side (Fig. 3a and b).

(a) After peritoneal dissection, a self-fixating mesh (ProGripTM; 15 × 10 cm2) was placed. Intraoperative laparoscopic view (right inguinal hernia). (b) After peritoneal dissection, a self-fixating mesh (ProGripTM; 13 × 9 cm2) was placed. Intraoperative laparoscopic view (left inguinal hernia).

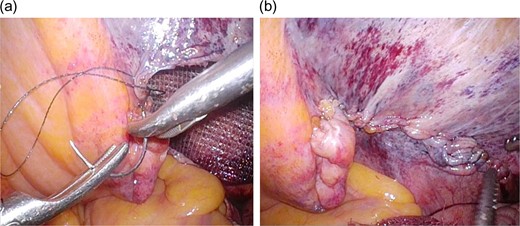

Although peritoneal closure is usually performed using 3-0 uninterrupted sutures, we used barbed sutures (V-LocTM) to facilitate strong and secure closure (Fig. 4a and b). The surgery duration was 100 min, and blood loss was 5 mL. There were no intraoperative complications.

a) Peritoneal closure was performed using uninterrupted barbed sutures (V-LocTM). Intraoperative laparoscopic view. (b) Intraoperative laparoscopic view following completion of peritoneal closure.

Postoperatively, except the appearance of seromas in the bilateral inguinal areas (Fig. 5), there were no major complications including exacerbation of liver cirrhosis or wound infection. He was discharged on postoperative Day 3 and remained alive and recurrence free for postoperative 6 months.

At the first examination following discharge, a mild seroma can be seen in the right inguinal area. However, there are no signs of recurrence or infection.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

DISCUSSION

Traditionally, surgical treatment of inguinal hernia has been avoided whenever possible in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis accompanied by ascites because of concerns regarding anesthesia-related and postoperative complications, exacerbation of liver function, and risk of ascitic leakage [4]. However, because pain can be severe due to the inflow of ascites into the hernia sac, surgery should be proactively considered [5].

Several reports have indicated the safety and efficacy of open inguinal hernia repair [1, 2]. Oh et al. evaluated postoperative complications and recurrence rate following McVay repair of inguinal hernia and reported no significant differences between patients with and without liver cirrhosis. They concluded that in patients with liver cirrhosis accompanied by ascites, elective surgery should be performed for symptomatic inguinal hernia [1]. Hur et al. reported successful surgical outcomes following inguinal hernia repair using the mesh–plug method under local anesthesia in 22 patients with liver cirrhosis accompanied by ascites. They recommended surgery to alleviate pain, prevent life-threatening complications, and improve quality of life, even in patients with poor liver function and ascites [2].

However, few reports exist on laparoscopic surgery for inguinal repair in cases accompanied by ascites. The guidelines state that similar to patients who undergo surgery for prostate cancer, those with ascites are considered difficult to treat and should undergo Lichtenstein repair [3]. Using propensity score matching, Pei et al. compared treatment outcomes between laparoscopic and open surgeries in patients with liver cirrhosis, as evaluated by a model for end-stage liver disease. They found that both approaches are feasible treatment options; however, they included only few cases with ascites and the significance of laparoscopic surgery remained unclear [6].

At our department, the standard procedure for inguinal repair is TAPP repair, indicated even for difficult cases, e.g. patients with recurrence following the posterior approach and those with a history of surgery for prostate cancer. We selected TAPP repair for this patient because we have successfully performed this procedure for above 1000 patients to date. Currently, TAPP repair is widely used and is a standard surgical procedure for inguinal repair [7]. We usually perform peritoneal closure using 3-0 uninterrupted sutures, and the usefulness of v-loc for peritoneal closure in TAPP has been described in a report, which stated that suture stress can be reduced particularly when inexperienced surgeons are involved [8]. Complications seemingly specific to v-loc including postoperative intestinal obstruction have been reported [9], requiring adequate care. Advantages of v-loc include no requirement for ligation, presence of barbs, and lower stress during suturing. In our case, standard TAPP without v-loc for peritoneal closure could have been possible without complications. However, for difficult cases wherein incomplete peritoneal closure can result in loosening and eventually cause complications, e.g. ascitic fluid leakage, v-loc can offer advantages of resistance to loosening, making it useful for safe, convenient, and quick peritoneal closure. We cannot conclude that v-loc is useful for peritoneal closure in patients with ascites, such as those with cirrhosis, based only on this case, necessitating accumulation of more cases.

TAPP repair was safely and successfully performed using barbed sutures to ensure accurate peritoneal closure. If the peritoneum is accurately closed, TAPP repair can be a useful treatment option, even for patients with liver cirrhosis accompanied by ascites.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None.

FUNDING

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.