-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ju Yee Lim, Enming Yong, Dokev Basheer Ahmed Aneez, Carol Huilian Tham, A simple procedure gone wrong: pneumothorax after inadvertent transbronchial nasogastric tube insertion necessitating operative management., Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 6, June 2019, rjz186, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjz186

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Nasogastric tube insertion (NGT) is a common bedside procedure and malpositioned tubes into the tracheobronchial are not uncommon. These can be associated with pulmonary complications. Significantly, pneumothoraces are rare but potential complications that clinicians need to be aware of. We herein report a case of pneumothorax following NGT insertion that necessitated operative management.

A 72-year-old male smoker was undergoing rehabilitation after a recent cerebrovascular accident. A NGT change was done and the chest radiograph done to check placement demonstrated the NGT in the right bronchus with the tip in the right pleural space. The NGT was removed and a new one reinserted. A repeat chest radiograph demonstrated a right sided pneumothorax. He underwent radiologically guided chest drain insertion and subsequently required thoracoscopic surgery where a wedge resection of the right lower lobe was performed. The chest drain was removed on day two post operatively and he made an uneventful recovery.

CASE REPORT

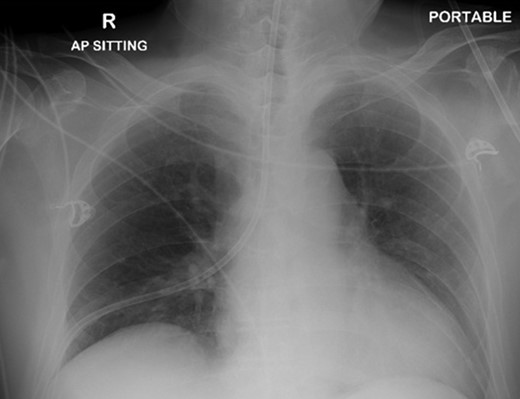

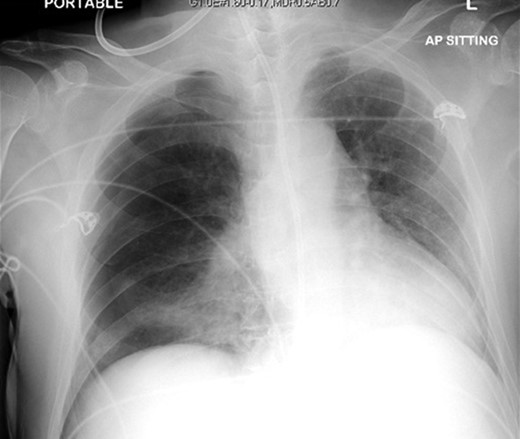

A 72-year-old male was admitted to a tertiary hospital following a cerebrovascular accident. His neurological deficits were global aphasia, dysphagia and right hemiplegia. He underwent a routine NGT change with a small bore NGT by an experienced nurse on Day 2 of admission. The nurse was unable to obtain any aspiration from the newly inserted NGT and a chest radiograph was done to confirm placement as per hospital protocol. This showed a malpositioned NGT, traversing the right main bronchus with the tip of tube in the right costophrenic sulcus (Fig. 1). She was alerted about the chest radiograph findings and removed the tube before reinserting another NGT. The subsequent aspiration from the NGT had a pH of 7, hence another chest radiograph was done which now demonstrated a right pneumothorax (Fig. 2). The pneumothorax was likely due to intrapulmonary placement of the earlier NGT.

Chest x-ray showing the nasogastric tube, traversing the right main bronchus with the tip in the right costophrenic sulcus.

Chest X-ray following removal of the nasogastric tube, with interval development of a right sided pneumothorax.

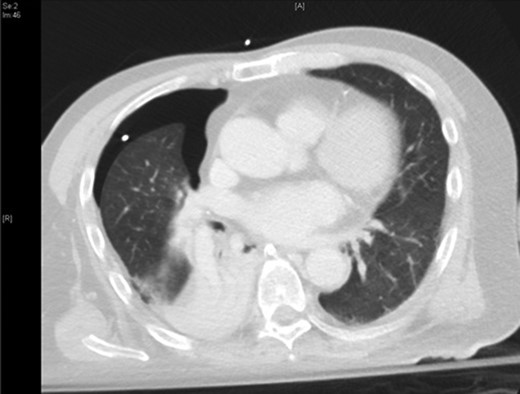

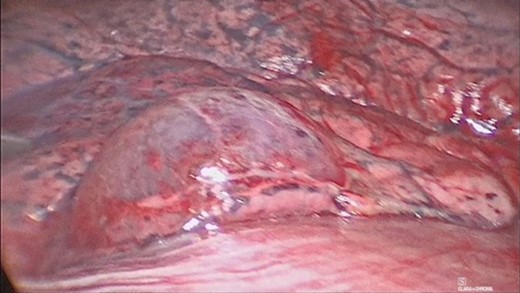

The patient was urgently reviewed by the cardiothoracic surgeons, and a small-bore chest tube was inserted, following which a computed tomography of the thorax was performed. This showed a residual but smaller pneumothorax with the chest tube in situ, associated with a small hemothorax (Fig. 3). Due to failure of conservative management and concern of a bronchopleural fistula resulting in air leak, he underwent explorative thoracoscopic surgery. Intraoperatively, an area of lung was noted with contusional changes and a bleb (Fig. 4), and a wedge resection of the right lower lobe was performed (Fig. 5). He made an uneventful recovery and was discharged.

Representative axial slice of computed tomography thorax showing a residual but smaller pneumothorax with the chest tube in situ.

Video assisted thoracoscopic surgery showing an area of right lung associated with a bleb and contusional changes.

DISCUSSION

Nasogastric tube insertion is a commonly performed bedside procedure. Indications for NGT insertion can be for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes such as for medication administration and nutritional supplementation as in our patient. As the insertion of the NGT is usually done without any imaging guidance, a malpositioned tube is hence not an uncommon occurrence. Potential rare and fatal complications include pneumothoraces and even internal jugular vein perforation as reported by Smith et al. in 2017 [1]. Malpositioned tubes into the tracheobronchial tree can happen from 0.3–15% [2, 3]. Pneumothorax has also been reported in up to 1.2% of patients in retrospective series [4]. Of note, transbronchial nasogastric tube insertion is potentially hazardous if feeding is commenced. Reported factors associated with pulmonary complications of feeding tube placement include altered mental status, smaller bore tubes and endotracheal intubation or tracheostomy [5].

In the majority of case reports, NGT associated pneumothoraces were seen on the same initial radiograph demonstrating the malpositioned NGT. Our patient’s case on the other hand is similar to the case published previously as the first known case of pneumothorax post NGT removal in BMJ Case series in 2013 [5]. Like in the previous case report, the pneumothorax in our patient was only present after the malpositioned NGT was removed. In addition, resolution of the pneumothoraces post NGT insertion in the literature was achieved with conservative therapy which involved the withdrawal of the offending nasogastric tube, placement of chest drains and lavage as required. However, as our patient’s pneumothorax did not resolve with conservative management, an operative management was mandated. To our knowledge this is the first reported case for which surgery was necessitated and with good outcome.

The nurse attending to our patient was following local nursing guidance on bedside NGT insertion. An appropriate feeding tube is first selected, after which the nasogastric aspirate is checked. If the pH of the aspirate is more than 6 or if no gastric aspirate is obtained, then a chest radiograph will have to be done to determine NGT placement [6]. If the pH of the aspirate is less than 5 then feeding can be started without the need for a chest radiograph. In our patient’s case, the nurse was unable to obtain any gastric aspirate after the first NGT insertion and the pH of the aspirate was more than 6 after the second insertion, therefore a chest radiograph was ordered in both instances. Roubenoff and Ravich proposed in 1989 a two-step approach in determining NGT positioning to detect malpositioned transbronchial placement of tubes before further injury such as a bronchopleural fistula occurs [7]. This first step of the approach involves inserting the NGT to level of xiphoid process then checking correct placement with a chest radiograph to ensure the NGT is in the oesophagus and not the bronchus. The second step involves further advancement of the NGT and then another chest radiograph to confirm the final positioning of the NGT. Mardenstein et al. demonstrated in their study that though the setting up of a specialized NGT placement team which implemented of an adapted two step process, the risk of NGT-related pneumothorax can be reduced [8]. However, in a busy tertiary hospital with limited staffing and already stretched resources, such as our hospital, this two-step process may be inefficient and impractical to implement. The two-step process also exposes patients to additional radiation risk and the extra cost involved in multiple chest radiographs.

A possible consideration for our hospital is to work on developing a similar two step approach for high risk patients such as our patient to prevent serious NGT associated complications.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.