-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Nimeshi S Jayakody, Morad Faoury, Lisa R Fraser, Sanjay Jogai, Nimesh N Patel, Composite poorly differentiated mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the thyroid and follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Report of a case and review of the literature, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 4, April 2019, rjz092, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjz092

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Mucoepidermoid variant of thyroid carcinoma is a rare and complex disease. Securing a diagnosis and formulating an evidence-based treatment plan is challenging. A case report of a patient with the dual pathology of a composite mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the thyroid and a follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma with malignant metastasis is presented in this article. We discuss the challenges in diagnosis, prognostic factors and management of this rare presentation by reviewing current literature.

INTRODUCTION

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC) is known to commonly arise in salivary glands but is also seen to occur in organs such as the lung, oesophagus, breast, pancreas and the thyroid [1]. Primary MEC of the thyroid is a rare tumour that is known to have a low-grade histological appearance [1, 2]. The histogenesis of this rare carcinoma has been in debate. MEC in thyroid gland has been theorized to originate from the remnants of the ultimobranchial body, intrathyroidal remnants of the salivary glands, the follicular epithelium, C cells, parathyroid and thyroglossal duct [1–3]. MEC is known to present with other variants of thyroid cancer such as papillary thyroid carcinoma [3].

CASE REPORT

A 71-year-old man was referred by his General practitioner to a district general hospital head and neck clinic with breathlessness and haemoptysis. On initial presentation the patient did not describe any changes in voice, dysphagia, odynophagia, weight loss with a prior smoking history. His past medical history revealed that 6 years previously, he had been fully investigated for a left vocal cord palsy of presumed idiopathic aetiology and had undergone medialisation of injection thyroplasty. Physical examination did not reveal any enlarged cervical lymphadenopathy of the neck. At fibre-optic nasal endoscopy he was noted to have a subglottic mass and therefore he was referred to a tertiary centre to be cared for under the head and neck multidisciplinary team.

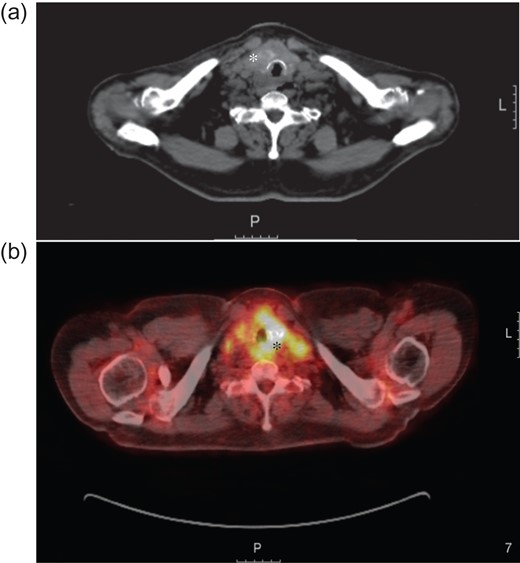

Computed tomography (CT) imaging depicted a paratracheal mass within the left trachea-oesophageal groove. Several enlarged lymph nodes were found in the antero-superior mediastinum and left paratracheal space as well as individual lymph nodes in the retrocaval, pretracheal and subcarinal regions. Ultrasound demonstrated several colloid nodules in the thyroid with abnormal heterogenous areas and focal areas of calcification. A positron emission tomography computed tomography (PET/CT) scan further identified lung and bony metastatic deposits. At microlaryngoscopy under general anaesthesia a subglottic mass was biopsied. The initial biopsy results showed stratified squamous epithelium that was hyperplastic and spongiotic with scattered and highly atypical cells with nuclear polymorphism and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Immunohistochemistry of these tissue samples showed positivity for Cytokeratin7 (CK7) and Periodic Acid Schiff Alcian (PAS-alc) blue and negativity for Cytokeratin20 (CK20) and Thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF1). Due to lack of evidence of thyroid markers on these tissues, an initial diagnosis of ‘mucoid’ tumour of the trachea was made. Based on this evidence, the tumour was staged at T4N2M1.

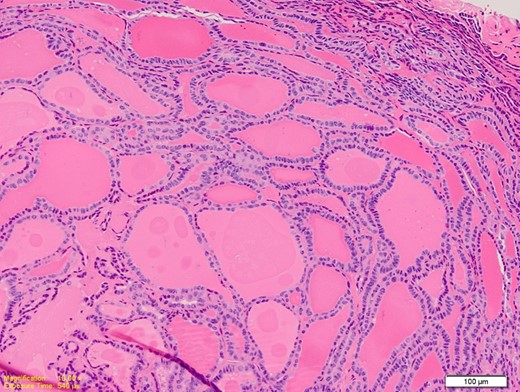

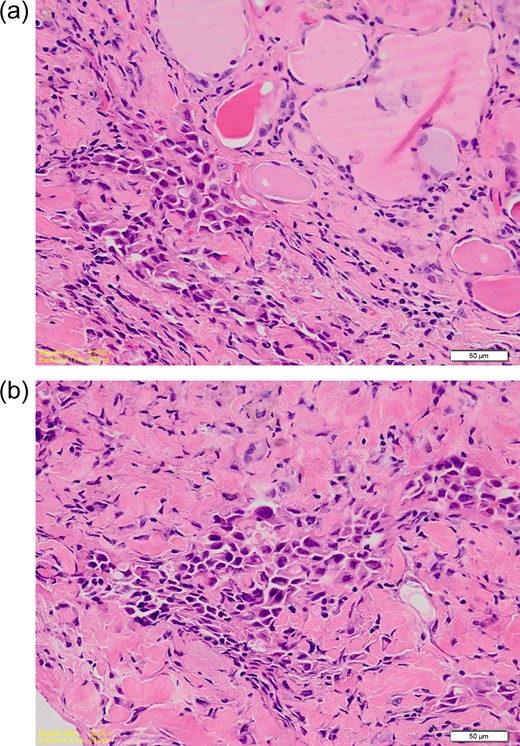

Clinical management of the patient involved microdebridement of the tumour under general anaesthesia and a palliative dose of radiotherapy (20 Gray in five doses) which failed to improve the patient’s airway obstruction. The patient underwent a surgical tracheostomy at which multiple further pathological samples were taken. These showed evidence of papillary thyroid carcinoma with a follicular growth pattern which was shown to blend imperceptibly with another component of tumour wherein the cells are present in irregular discohesive infiltrating growth pattern. The nuclei of these cells were found to be hyperchromatic with moderate cytoplasm, whilst several of the cells showed intracytoplasmic lumen and eosinophilic inclusions. Immunohistochemistry showed positivity for TTF1 and thyroglobulin in the papillary component of the carcinoma whilst the poorly differentiated area showed negativity for TTF1 and weak positivity for thyroglobulin. This led to the diagnosis of a follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma with composite MEC of the thyroid. Due to the extensive nature of the disease, the patient was managed with palliative intent and died 2 months later (Figs 1–3).

(a) Axial computed tomography image showing a thyroid mass (white asterisk) extending in to the trachea and invading the surrounding tissue. (b) Axial positron emission tomography (PET)/computer tomography image taken as part of the staging investigations, showing the thyroid mass with local invasion (black asterisk). L = Left.

Medium power photomicrograph showing closely packed thyroid follicles containing thick colloid. The follicles are lined by elongated overlapping nuclei (H&E; ×20).

(a) High power photomicrograph showing overlapping nuclei with grooves and pseudoinclusions. (b) High power photomicrograph showing poorly differentiated tumour cells with hyperchromatic nuclei. Occasional intracytoplasmic lumina are seen. The features are consistent with a mucoepidermoid component. (H&E; ×40).

DISCUSSION

Occurrence of MEC in the thyroid as a primary tumour occurs in <0.5% of thyroid tumours [3]. Although there have been reports of ~50 cases of primary mucoepidermoid carcinoma in literature, in a literature search involving EMBASE, MEDLINE and OVID 22 cases of mucoepidermoid occurring with concurrent papillary thyroid cancer were noted. But the presence of MEC with the ‘follicular variant’ of papillary cancer is even rarer with only two cases which has been described before [4, 5].

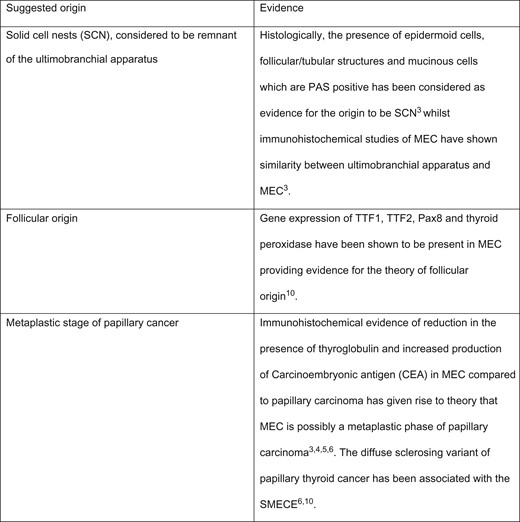

The origin of this type of cancer has been debated with several theories suggested (Fig. 4). Two microscopic variants of this carcinoma have been identified according to the histological content of the tumour tissue: mucoepidermoid (MEC) and sclerosing mucoepidermoid carcinoma with eosinophilia (SMECE) [3, 6]. The histological appearance of MEC has been defined by the presence of squamous and glandular differentiation within an uninflamed gland [3]. Conversely, SMECE is categorized by the presence of sclerosis and a concomitant eosinophillic infiltrate with a past history of thyroiditis most commonly Hashimoto’s [3]. Immunohistochemistry studies of MEC have shown changes to the cell adhesion complexes such as the new expression of P-cadherin in MEC compared to papillary tumours [3, 4, 7]. The cells that are frequently described as being present in MEC are squamous epithelial and mucinous cells which stain positive for Alcian blue stain [3–5]. Both these were identified in the histological samples of our case, justifying the diagnosis of MEC. Various reports have suggested mucoepidermoid cancer as a metaplastic transformation stage of papillary thyroid cancer [3, 4, 6]. The presence of these two types of cancer in adjacent tissues in our case, would also support this theory.

Table with suggested origins of the mucoepidermoid cancer arising from the thyroid.

In the past primary mucoepidermoid tumours of the thyroid have being described as having indolent behaviour, although those tumours that have been locally invasive or those which have presented with concurrent papillary and mucoepidermoid components have been noted to be more aggressive [4–6, 8]. In cases with only locoregional spread, treatment with total thyroidectomy, neck dissection and external radiation, has been shown to give good clinical outcomes [6]. But direct invasion into neck viscera has been shown to be a poor prognostic factor and in such cases treatment with surgery and radiotherapy have been unsuccessful in halting advancement of the disease [6, 8, 9]. Early histopathological diagnosis prior to spread by direct invasion is therefore advantageous in prognosis and treatment options [6, 8].

Dual pathology in thyroid cancer is a rare histopathologial entity and provides a diagnostic challenge particularly when the patient presents atypically. The tumour had poor prognostic features at diagnosis and was treated with palliative intent. An agreed management protocol remains to be developed for dual thyroid cancer pathology.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.