-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Dimitrios Katsarelias, John Båth, Per Carlson, Jan Mattsson, Roger Olofsson Bagge, Leakage through the bone-marrow during isolated limb perfusion in the lower extremity, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 4, April 2019, rjz090, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjz090

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Isolated limb perfusion (ILP) is used for melanoma in-transit metastases of the extremities. The use of Melphalan and TNF-alpha, necessitates monitoring of possible systemic leakage throughout the perfusion. It has been suspected that leakage through bone marrow is possible. We present the case of a patient with in-transit melanoma metastases in the lower extremity, who underwent minimally invasive ILP, according to our new protocol through percutaneous insertion of the catheters under fluoroscopy. Following cannulation of the vessels a high leakage rate was recorded. The procedure was converted to open with clamping of the artery and vein, however the leakage was not possible to control, and venography showed that this was due to bone marrow veins. To the best of our knowledge this is the first case of a verified leakage during ILP through bone marrow veins. We believe that some minor leakages registered under ILP could be attributed to this leakage route.

INTRODUCTION

Isolated limb perfusion (ILP) is used as treatment for malignancies of the extremities when surgery is not feasible. The indications are mainly melanoma in-transit metastases and soft-tissue sarcomas, but also other malignancies have been reported [1–4]. The technique was originally described in the 1950 s by Creech and Krementz, and has been refined since then [5]. ILP combines surgical isolation of the limb and extracorporeal circulation allowing for regional perfusion with chemotherapeutic agents. Surgical access is gained by open vascular dissection of the extremity and clamping and cannulation of the major artery and vein. The cannulas are connected to an oxygenated extracorporeal circuit and collateral circulation is controlled by placement of a tourniquet proximally around the extremity. We recently developed a minimally-invasive ILP technique where vascular access is accomplished by percutaneous placement of the catheters by ultrasound and angiography [6].

The use of high doses of melphalan, as well as TNF-alpha, necessitates continuous leakage monitoring [7]. Systemic toxicity due to leakage has been reported previously [7, 8] and proper catheter selection and mechanical isolation are considered crucial. The highest acceptable level of leakage is considered to be 10%, since higher levels of melphalan may lead to bone marrow depression [7]. Even with meticulous isolation of the extremity there might be smaller amounts of leakage, and it has been hypothesized that this leakage could be through veins within the bone. However, to our knowledge, no evidence supporting this hypothesis has been presented so far. We now present a case where we were able to identify and visualize a leakage through a vein within the bone marrow during ILP.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

A 65-year-old, healthy female patient, previously operated for a T3bN0M0 melanoma, had recently presented with in-transit metastases in the left lower extremity (stage IIIC) and she was referred for ILP.

Under general anesthesia, percutaneous ultrasound guided femoral vein and artery cannulation was performed, using an 8 Fr and a 10 Fr Bio-Medicus® NextGen Pediatric Cannulae (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Double Esmarch bands were applied proximally and the catheters were connected to the perfusion system. Continuous leakage monitoring using a precordial scintillation probe (Medic View, Sweden) was used to detect and measure leakage of technetium-99 m labeled human serum albumin (Vasculosis, Cis-Bio International, Gif-sur-Yvette, France) injected into the perfusion circuit.

After cannulation, perfusion was started with a flow of 300 ml/min, but an unusually high systemic leakage was recorded. The flow rate was reduced and the Esmarch bandages were tightened, but leakage rate did not decrease. In our minimally-invasive approach we use cannulas with smaller external diameter and therefore our first concern was that leakage could potentially be caused by incomplete proximal isolation of the femoral artery and vein. Therefore, the procedure was converted to open surgery and femoral artery and vein was dissected and isolated with vessel tourniquets according to our standard technique for open ILP.

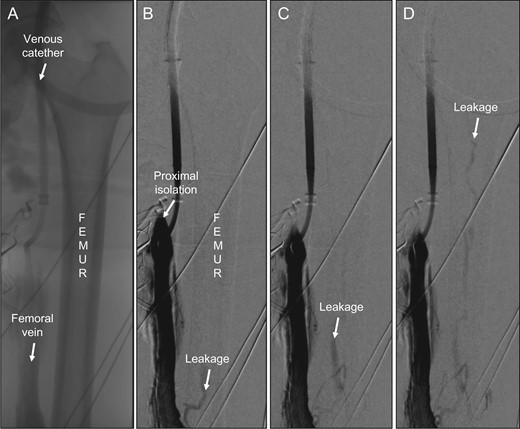

After re-application of Esmarch bands, there was still a high leakage rate. We performed a venography, which verified that there was no proximal femoral vein leakage. However, somewhat surprisingly, there was venous leakage through the femoral shaft that was clearly identified and recorded (Fig. 1A, 1B). A repeated venous angiogram confirmed a high venous flow through the nutrient medullary venous system of the femur (Fig. 1C) which caused the high leakage recorded by the precordial scintillator probe. The leakage made it impossible to continue with the perfusion. We decided to stop the perfusion, the patient never received any melphalan and she was afterwards referred for treatment with immunotherapy.

(A) Overview showing femur, the femoral vein and the venous catheter in place. (B) First venography showing the site of proximal isolation and leakage through the medullary vein in femur (arrow). (C) Successive image with proximal direction of leakage flow within the femur (arrow). (D) Continuous leakage through bone marrow up to femoral head (arrow).

DISCUSSION

It is known that the diaphysis of long bones has a so-called nutrient foramen were the nutrient artery and vein enters the bone cortex in order to supply the medullary channel with blood. Several studies have demonstrated the structure of the intramedullary vascular net in both humans and animals, and they have also demonstrated anatomical variations, mostly concerning the position of the foramen, which can be found at the level of the metaphysis or epiphysis. The venous flow in the mature long bone is usually centripetal (outside to inside) and all venous sinusoids drain into the emissary venous system. There are several variations in the interconnections between emissary and cortical veins at the different levels of the bone, in this case the femur, namely epiphyseal, metaphyseal, diaphyseal and nutritive veins [9, 10]. In our case the connection was between the external femoral and the nutritive vein, which following the abovementioned centripetal flow, drained into the metaphyseal or epiphyseal veins to gain access in the systemic circulation and thus causing the systemic leakage.

Since ILP is by definition a regional therapy all anatomical structures that could present a possible leakage source should be isolated. The use of high doses of melphalan and/or TNF-alpha necessitates leakage monitoring during perfusion. Lower extremity isolation includes isolation of the femoral artery and vein, the area of the gluteal artery and vein as well as collaterals. Since isolation of vessels within the bone is not feasible by mechanical means, attention is paid to accurately isolate the former structures. In most of the cases this is feasible by properly selecting the right diameter of cannulas and by proximal compression of the limb using a tourniquet [7].

It has been assumed among ILP surgeons that a potential leakage route could be through the bone (femur or humerus), but to our knowledge any evidence of this has never been reported. In this case, the patient was operated in a hybrid operating theater allowing for an intra-operative venous angiography showing this leakage route. Since the leakage is less than 2% in almost 95% of ILPs [7], this leakage route probably only have a minor impact concerning systemic toxicity. This potential leakage route can present even in Isolated Limb Infusion (ILI), but since TNF is not used and pressures are low, it has a minor impact when opposed to ILP. However, in some patients we believe that this route of leakage should be considered when unexpectedly high leakage rates are recorded during perfusion.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- surgical procedures, minimally invasive

- catheterization

- drug administration routes

- limb

- fluoroscopy

- melanoma

- melphalan

- neoplasm metastasis

- perfusion

- venography

- bone marrow

- leg

- catheters

- isolated limb perfusion

- tumor necrosis factor-alpha

- in-transit metastasis

- verification

- cutaneous melanoma in-transit metastasis