-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Yasir Abdu Mahnashi, Abdullah Mohammed Alshamrani, Mohammad Abdulaziz Alabood, Ali Mohammed Alzahrani, Rami Abdulrahman Sairafi, Laparoscopic management of cecum and ascending colon hernia through the foramen of Winslow, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 2, February 2019, rjz026, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjz026

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Herniation of gastrointestinal structures through the foramen of Winslow is rare, with patients presenting with nonspecific symptoms. We describe a 47-year-old woman who presented with generalized, intermittent, colicky abdominal pain for a duration of 4 days. An abdominal computed tomography scan revealed findings consistent with herniation of the ileocecal junction through the foramen of Winslow. Laparoscopic assisted internal hernia reduction with ileocecal resection and side-to-side ileocolic anastomosis were done. The cecum and terminal ileum were resected due to signs of ischemia. Her postoperative was uneventful, and she was discharged in the second postoperative day. She did not show any signs or symptoms suggestive of complications or recurrence during her follow-up.

INTRODUCTION

Foramen of Winslow hernias are rare, accounting for only 8% of internal hernias [1]. Any of the viscera (the small intestine, cecum, transverse colon, gall bladder) can be involved, and most patients present with epigastric pain [2]. Predisposing factors include anatomical anomalies, including a large foramen of Winslow, redundancy of mesentery or mesocolon, and partial adhesion of the intestines to the posterior abdominal wall [2]. Other factors such as pregnancy and overeating, which can augment intra-abdominal pressure, have been reported to predispose patients to foramen of Winslow hernias [1, 3].

The condition is often under-recognized, resulting in diagnostic and treatment delays, with a mortality rate of up to 49% [4]. However, with the widespread use of advanced diagnostic imaging techniques such as computed tomography (CT), the mortality rate has considerably decreased to 5% [5]. Unfortunately, physicians are still faced with treating patients with foramen of Winslow hernias. Most case series favor laparotomy [6, 7], and only a few reports have preferred laparoscopy [1, 8]. In cases where the herniated bowel is still viable, treatment involves the reduction of the hernia and prevention of recurrence. There is, however, a paucity of reports describing challenges in using laparoscopic techniques in patients with complicated cases, such as bowel incarceration through the foramen of Winslow.

We present a case of a female patient with generalized abdominal pain in whom an abdominal CT scan revealed findings consistent with internal herniation through the foramen of Winslow.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 47-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with generalized abdominal pain for a duration of four days. The pain was intermittent and colicky in nature with a mild response to analgesia. It was associated with vomiting and abdominal distension, with absolute constipation. The patient denied experiencing a similar previous attack. Her medical and surgical histories were unremarkable, and she reported only having an irregular menstrual cycle. She also reported no history of trauma.

Upon physical examination, the patient was found to have stable vital signs: temperature, 36.7°C; heart rate, 88 beats per minute; and oxygen saturation, 100% room air. An abdominal examination revealed mild abdominal distention with generalized tenderness but no guarding or rigidity; the abdomen was tympanic to percussion, and a digital rectal examination was unremarkable. A provisional diagnosis was made for intestinal obstruction.

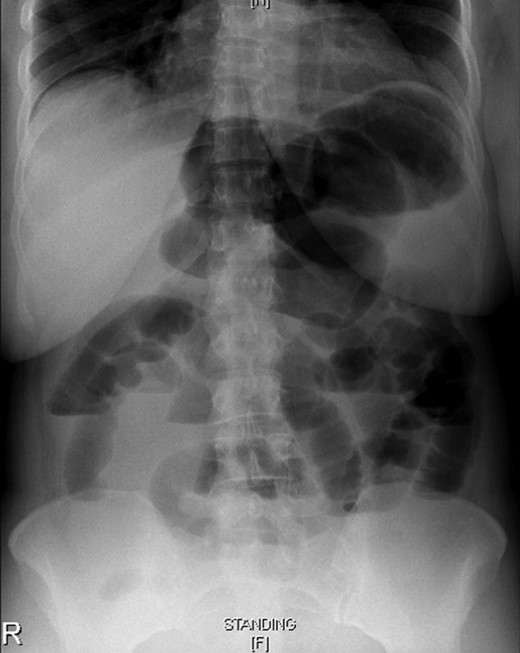

Laboratory investigations, including a complete blood count, urea and analysis, and coagulation profile, were all within normal limits. An abdominal X-ray showed a dilated large bowel with few air fluid levels, no gas in the rectum and no air under the diaphragm (Fig. 1). An abdominal CT scan with oral and intravenous contrast showed that the cecum was flipped superiorly and positioned anteriorly to the transverse colon, and it herniated into the foramen of Winslow (opening between the inferior vena cava and portal vein). The cecum occupied the lesser sac, and it was distended with gas and caused a mass effect on the stomach and hepatic root, with associated intrahepatic bile duct dilatation. This was associated with proximal small bowel dilatation and collapsed large bowel loops distally (Fig. 2). These findings were consistent with an obstructive internal hernia into the lesser sac through the foramen of Winslow.

Erect abdominal X-ray showing proximal small bowel dilatation with multiple air fluid levels suggestive of bowel obstruction.

Coronal section of abdominal computed tomography scan showing the cecum (C) flipped superiorly and positioned anterior to the transverse colon and herniated into foramen of Winslow. The cecum occupies the lesser sac, and it is distended with gas, causing a mass effect on the stomach (S) and hepatic root with associated intrahepatic bile duct dilatation. This is associated with proximal small bowel dilatation and collapsed large bowel loops distally.

A surgical consultation was requested, and laparoscopic assisted internal hernia reduction with ileocecal resection and side-to-side anastomosis were offered. The cecum and terminal ileum, along with the appendix, had herniated through the foramen of Winslow as evidenced during laparoscopy (Video 1). Both the cecum and terminal ileum were markedly distended and probably less vascularized (Fig. 3). Consequently, the cecum and terminal ileum were resected (Fig. 4).

The bowel is retrieved through an Alexis retractor for better evaluation of devascularization.

Gross appearance of the resected ileocecal with a dusky coloration.

The patient’s postoperative was uneventful. She was started on a clear liquid diet and then advanced to solid foods by Day 2. The patient was discharged, and she did not show any signs or symptoms suggestive of complications or recurrence during the last follow-up.

DISCUSSION

In recent reports, hernia reduction was infrequently associated with cecopexy in patients with ileocecal involvement [9, 10]. According to some authors [2], a right colectomy is the preferred option in patients with bowel ischemia. Other authors reported performing needle bowel decompression to reduce incarcerated hernias, but the procedure was only performed under laparotomy and/or followed by resection of the right colon [1]. In 2011, laparoscopy was successfully used in a patient with a foramen of Winslow hernia [10]. Thereafter, several investigators reported the safety and feasibility of the laparoscopic approach, even in cases that required bowel resection [8]. Thus, the best approach is to offer laparoscopic surgery in instances where the diagnosis is preoperatively suspected. In this case, we adopted a laparoscopic approach and reduced the internal hernia, followed by ileocecal resection and side-to-side anastomosis.

The patient in our report presented with unspecific abdominal symptoms, as is typically the case in patients with foramen of Winslow hernia. The differential diagnosis is broad due to the nonspecific nature of the symptoms and should include acute abdomen cases; gynecological diseases should also be considered in women. Nevertheless, the increasing use of imaging techniques has facilitated the pre-operative diagnosis, with abdominal CT scan recommended as the preferred imaging modality [6, 7]. In our patient’s case, abdominal CT scan findings, including the presence of a distended cecum in the lesser sac, with associated intrahepatic bile duct dilatation, as well as proximal small bowel dilatation and collapsed large bowel loops distally suggested the diagnosis. These findings permitted us to identify the condition and provide timely surgical treatment.

In previous reports of herniation through the foramen of Winslow, the most common gastrointestinal tube that was involved was the small intestine (63%), followed by the cecum and ascending colon (30%); in only 7% of the cases, herniation involved the transverse colon [8]. Cases of gall bladder herniation [3] or a small bowel diverticulum [5] have been reported [6]. The outcome is generally favorable in these cases after surgery, with one report describing a 0% mortality rate in a review of cases published before 2011. In our patient, her postoperative was uneventful; she was discharged early and did not present any complications or recurrence during follow-up visits. We did not close the foramen in our patient due to the high risk of iatrogenic injury in this area (hepatic vessels) and the fact that the foramen may be obliterated by postoperative adhesions, making it unnecessary to close it surgically. Additionally, no consensus has been reached regarding the prevention of future herniation by closing the foramen closure, performing cecopexy or resecting the intestine. In practice, recurrences have also not been described in patients who have had laparoscopic surgery for foramen of Winslow herniation.

Overall, foramen of Winslow hernias are rare, and patients typically present with unspecific gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain. Imaging modalities can help clinicians make an early diagnosis and provide timely surgical intervention. A laparoscopic may be ideal in cases diagnosed preoperatively.

Conflict of Interest statement

None declared.