-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Abdullah Ibrahim, Senarath Edirimanne, Portal venous gas and pneumatosis intestinalis: ominous findings with an idiopathic aetiology, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 2, February 2019, rjy352, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy352

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Pneumatosis Intestinalis and hepato-portal venous gas are rare but ominous radiological findings that are synonymous with mesenteric ischaemia and bowel infarction in the majority of cases. Very uncommonly benign pathology have been implicated, including respiratory and inflammatory bowel disease. We provide a case of a 69-year-old gentleman with extensive peripheral vascular disease, who presented with generalized abdominal pain and findings of both pneumatosis intestinalis and hepato-portal venous gas. Laboratory investigations were unequivocal, with only mild lactatemia. Emergency laparotomy was performed, which revealed no obvious cause and only some turbid pelvic free fluid. The patient had an uncomplicated recovery. This case illustrates the importance of guiding decisions based on the patient’s clinical state, and of keeping an open mind to benign pathology. It also highlights the importance of early surgical intervention in cases of high clinical suspicion.

INTRODUCTION

Hepato-portal venous gas (HPVG) in combination with pneumatosis intestinalis (PI), are ominous findings that are clinically synonymous with mesenteric infarction and herald the need for urgent surgical intervention. Although benign cases of PI or HPVG have been reported in the literature, they remain uncommon. Even rarer are cases of simultaneous benign PI and HPVG. In this case report we describe a 69-year-old gentleman who presented with generalized abdominal pain and CT findings of small bowel PI and extensive portal venous gas. Remarkably subsequent laparotomy was negative for any mechanical or ischaemic cause, and the patient had complete recovery.

CASE REPORT

A 69-year-old gentleman presented to our emergency department with a third presentation of generalized abdominal pain over a 2-week period. His recent presentation was due to constipation, without vomiting or diarrhoea. He had significant vascular risk factors including hypertension, ischaemic heart disease, peripheral vascular disease with bilateral below knee amputations, type 2 diabetes, and end stage renal failure managed with haemodialysis. He had no other surgical history.

On examination he appeared unwell and drowsy. He had a distended abdomen with generalized abdominal tenderness without guarding or rebound tenderness. He was tachycardic with a heart rate of 105, but was normotensive, and otherwise stable and afebrile. Laboratory investigations were unremarkable with haemoglobin of 118 mg/dL, a white cell count of 11.3 (×109), a mild CRP rise of 17 mg/L and a lactate of 3 mmol/L.

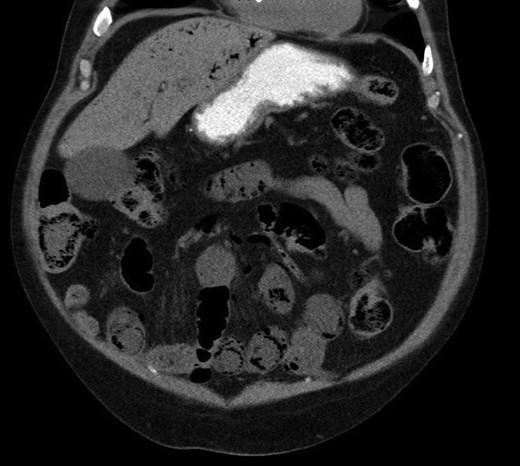

A CT with mesenteric angiogram was organized as the patient’s pain had not resolved despite him opening his bowels post enema. The CT imaging revealed some mildly distended and thickened bowel loops in the distal jejunum and ileum, with gas in the bowel wall (PI) and extensive gas tracking through the portal vein and into the hepatic venous tree (Fig. 1). No other organ or vascular abnormality was noted.

Pneumatosis intestinalis in jejunal and ileal loops, with hepatic venous gas evident.

An urgent laparotomy was performed. Intraoperatively no abnormality was detected, with good integrity of small and large bowel walls, strong mesenteric arterial pulsation, and normal peristaltic flow. A small amount of turbid free fluid was found in the pelvis, and was sent for microbial analysis. No suspicious organisms were found. The remaining intra-abdominal organs were healthy, and no other surgical intervention was required. The patient recovered well, and was discharged home on post-operative Day 5.

DISCUSSION

Cases of PI and HPVG with benign aetiology have rarely been reported in the literature [1]. The combination of the two almost always indicates underlying mesenteric infarction and bowel necrosis [2]. This carries a poor prognosis, with a mortality rate between 39 and 80% [2–4], and in some series approaching 100% [2].

PI usually presents in two patterns, PI cystoides and linearis, with the former being more likely to be benign [1]. The incidence of PI remains low around 0.03% [1]. There are many causes for PI, both benign and life threatening (mainly bowel necrosis) [2]. Two main theories exist regarding the pathogenesis of PI [1]. A mechanical theory postulates that gas dissects into the bowel wall due to increased intraluminal pressure or from the lungs via the mediastinum (e.g. bowel obstruction, CPAP in COPD patients) [1–3]. An alternative bacterial theory predicts that gas forming bacteria gain access into the bowel wall to form gas pockets [1–3]. It is difficult to differentiate benign from life-threatening causes based on imaging alone [3]. The patient’s clinical picture and laboratory findings should guide this decision instead.

HPVG was first described in 1955 in children with necrotizing enterocolitis [5]. The aetiology and pathophysiology of HPVG are essentially the same as PI. HPVG often represents the natural progression of PI and with the pattern of portal gas often reflecting the draining tributaries of the bowel segments involved [3, 6]. The presence of both PI and HPVG is often more ominous as outlined above [3, 7]. Again, however HPVG may be due to benign pathology such as enterocolitis, or localized obstruction [6]. It is also worth noting that HPVG can occur in isolation [3]. Idiopathic PI and HPVG, such as our case, are extremely rare [3].

Despite their rarity, the incidence of PI and HPVG is increasing due to increasing use of CT imaging in the diagnosis and work up of abdominal presentations [1]. Given their prognostic significance, the management of PI and HPVG remains an issue of intense contention [3, 7–9]; especially when considering that the stakes include death or committing patients with possible benign pathology to laparotomy.

Several algorithms have been developed with the aim of distinguishing patient subsets that will require urgent surgical intervention from those with benign pathology who would not. Wayne et al. [3] established an algorithm based on 88 presentations of PI and/or HPVG that relied on physical examination, lactate levels and a vascular score based on medical history. Their algorithm was reported to be 89% sensitive and 100% for ischaemic versus benign pathology [3]. Kaomi et al. [8], in their series of 33 patients found that peritoneal signs, hypotension and lactate dehydrogenase levels were independently associated with necrosis. Two other series by Duron et al. [9] and Bani Hani et al. [7] also found that peritoneal signs were significant, but differed on other risk factors.

All the above studies were limited by small sample size, but all agreed on the importance of peritonitis and its physical manifestations as a predictor of bowel compromise. It is thus our opinion, that caring clinicians should rely on the patient’s clinical state; especially any signs of peritonitis and other laboratory adjuncts when making a decision to operate. In most studies, there is an agreement that when in doubt, and in patients who can tolerate surgery, then exploratory laparotomy or laparoscopy is justified [2–4]. This is especially true given the high mortality associated with their underlying pathology. If the clinical state permits, diagnostic laparoscopy should be considered first as it is less invasive. If surgery is contemplated, operative mortality risk should be estimated using an existing risk assessment tool such as P-POSSUM [10], and discussed with the patient or family, as invasive surgery may conflict with patient interests, especially in the elderly or those with advanced life directives.

In conclusion, we present a case of PI and HPVG with negative laparotomy and a favourable outcome. This demonstrates that not all cases of PI and HPVG are life threatening, and the patient’s clinical state and laboratory findings must guide decision making and management. Lastly if in doubt and if clinically safe then early diagnostic laparotomy or laparoscopy is justified given the high mortality rate associated with these radiological findings.

Acknowledgements

Nil.

Conflict of Interest statement

None.