-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jessica K Staszak, David Buechner, Ryan A Helmick, Cholecystitis and hemobilia, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 12, December 2019, rjz350, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjz350

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Hemobilia, or hemorrhage into the biliary system, is an unusual cause of gastrointestinal bleeding most commonly seen in accidental or iatrogenic trauma. We present the rare case of a 43-year-old gentleman who presents with an intrahepatic pseudoaneurysm caused by cholecystitis. The management of the hemobilia was technically challenging requiring multiple interventional procedures. We review the pathophysiology and treatment strategies for this rare case of gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

INTRODUCTION

Hemobilia is a rare but increasingly recognized phenomenon whereby a patient experiences hemorrhage into the biliary system. Three large series looking at the causes of hemobilia identify trauma as the by far most common etiology, with a shift over recent years from accidental trauma to iatrogenic. [1] Vascular malformations account for only about 10% of hemobilia reports, with hepatic artery aneurysms being the most common of these etiologies. As infectious causes of hepatic artery aneurysm have been on the decline due to improvements in antibiotics and early detection, this etiology is similarly less commonly identified.

CASE REPORT

A 43-year-old male with history of myocardial infarction and hypertension presented with 1 month of right upper quadrant pain, nausea and vomiting. His initial imaging and lab work indicated cholestasis without evidence of acute cholecystitis. He had an incidental finding of an intrahepatic arterial pseudoaneurysm in segment 4b, just superior to the gallbladder fossa. Over the next 24 hours, his white blood cell count and total bilirubin dramatically increased, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with stent placement was performed urgently for worsening cholangitis. An uneventful laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed the next day. On postoperative day 2, his hemoglobin dropped to 5.8 g/dL, and the patient suffered both hematemesis and melena. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen showed there was no postoperative fluid within the gallbladder fossa, precluding any surgical bleeding. Upper endoscopy identified blood coming from the ampulla of Vater and ERCP demonstrated clots within the common bile duct. He proceeded urgently to interventional radiology for embolization, which was complicated by the tortuous nature of his hepatic artery. Onyx (a liquid non-adhesive embolic agent comprised of Ethylene Vinyl alcohol) injection of the artery occluded the feeding vessel but did not fill the pseudoaneurysm cavity. The patient stabilized temporarily but had ongoing bleeding, presumably from a backfill bleeding phenomenon like a type II endoleak. Injection of the hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm with Onyx under CT guidance was ultimately successful at stopping the bleeding entirely.

DISCUSSION

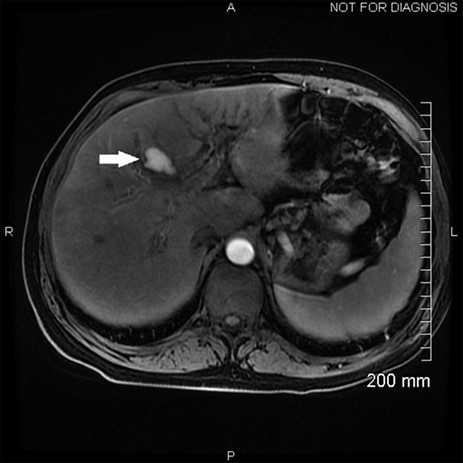

Hemobilia, as seen on this patient’s ERCP, can result from a variety of pathologies though is usually a result of instrumentation of the biliary tract and injury to a nearby vessel [2]. In this case, a hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm formed during his severe cholecystitis, as seen on his MRCP at presentation (Fig. 1). MRI of the abdomen with MRI cholangiogram demonstrated cholelithiasis and pericholecystic edema consistent with cholecystitis. In addition, a 2.6 cm pseudoaneurysm was identified superior to the gallbladder along posterior margins of segment 4A. This is best appreciated on the arterial sampling phase of the liver acquisition with volume acceleration sequence (GE medical systems; Milwaukee, Wisconsin). While pseudoaneurysm due to cholecystitis is rare, the treatment is the same as for any other life-threatening hemorrhage due to arterial fistula to the biliary system, hepatic angiography and transcatheter arterial embolization [2, 3] (Fig. 2). The classic presentation of hemobilia is described by Quinke’s triad: right upper quadrant pain, jaundice and gastrointestinal bleeding, with all three present in only 25–33% of cases [4].

Angiography showing the hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm filling, with the arrow pointing to the catheter used for embolization.

The pathophysiology of hepatic or cystic artery pseudoaneurysm in the setting of cholecystitis is largely unknown; however, one hypothesis suggests that the presence of bile in the inflamed tissues after cholecystectomy causes breakdown of blood vessel wall, subsequent blood leak and formation of a sac, particularly in the presence of an undetected iatrogenic injury. Slow oozing from a minor injury typically remains clinically silent or results in melena that resolves spontaneously [5]. When this occurs preoperatively, it is most likely due to severe inflammation in the gallbladder bed.

Appropriate work-up for any gastrointestinal bleed begins with localization. In this case, the patient had both hematemesis and melena indicating a likely upper source. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is the next step that allows for both diagnosis and potential treatment of a bleeding vessel, ulcer or area of oozing. When blood is seen coming from the ampulla, concern for hemobilia arises [6]. A recent publication from the University of California illustrates the role of the advanced endoscopist as an alternate first-line therapy for hemobilia when found on EGD or ERCP, using described hemostatic techniques such as epinephrine injection, mono- or bi-polar coagulation, fibrin sealants, hemoclips or others [4].

A variety of embolic material choices are available when interventional radiologists perform transcatheter arterial embolization techniques to treat hemobilia. In a 2012 study by Marynissen et al., with a small cohort of patients (n = 12), the most common choice was micro coils, followed by a mixture of enburylate and ethiodized oil, and particles mixed with micro coils. They had a 100% success rate, with minimal complication. The most common complications are related to groin access techniques, with some reversible hepatic ischemia and transient rise of transaminases [7].

In summary, when a patient presents with either upper or lower gastrointestinal bleeding and current or recent biliary pathology, the correct action is to stabilize the patient and pursue localization with clinical, endoscopic and imaging techniques. It is important though to keep in mind the rarer possibilities of hemobilia and hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm.

Conflict of Interest statement

None declared.