-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ryohei Murata, Yo Kamiizumi, Yasuhiro Tani, Chihiro Ishizuka, Sayuri Kashiwakura, Takeshi Tsuji, Hironori Kasai, Tsutomu Haneda, Tadashi Yoshida, Hidenori Katano, Koji Ito, Spontaneous rupture of the urinary bladder due to bacterial cystitis, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2018, Issue 9, September 2018, rjy253, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy253

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We report a case of spontaneous rupture of the urinary bladder (SRUB) due to bacterial cystitis in a 76-year-old woman with chief complaint of abdominal pain a day before presentation. She had fever (38.0°C), and her systolic blood pressure dropped to 70 mmHg; she was referred to our hospital, where she was admitted with a diagnosis of ileus. However, her abdominal pain worsened the following day, and abdominal CT showed free air. Emergency laparotomy was performed for suspicion of digestive tract perforation, which revealed a small hole at the dome of the urinary bladder and another at the peritoneum. Suture repair was performed. We reviewed the abdominal CT on admission and noted that the perforation of the urinary bladder was present during admission, whereas that of the peritoneum occurred the following day. SRUB is rare, and bacterial cystitis rarely causes it; thus, accurate diagnosis and proper treatment are essential.

INTRODUCTION

Almost 96.6% of urinary bladder ruptures are due to traumatic causes, and spontaneous rupture of the urinary bladder (SRUB) is very rare. The diagnosis is sometimes difficult, and missed or delayed diagnosis often causes problems [1]. We report a case of urinary bladder rupture due to bacterial cystitis that was initially misdiagnosed but was eventually treated successfully.

CASE REPORT

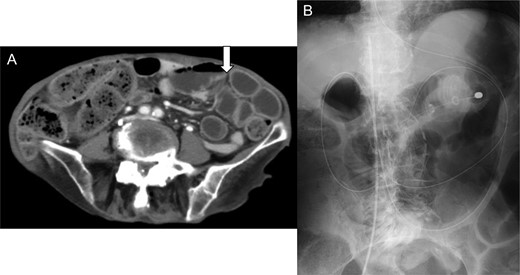

A 76-year-old woman, under the care of a home nurse, had pain on the entire abdomen since the day before presentation to our hospital. She had fever (38.0°C), and her systolic blood pressure dropped to 70 mmHg, and thus, she was referred to our hospital. She was alert and with body temperature of 37.9°C, blood pressure of 83/52 mmHg, heart rate of 103 beats/min, respiratory rate of 30/min, and oxygen saturation of 80% (with 6-L/min mask-to-face ventilation). On physical examination, her abdomen was soft and flat, but she felt tenderness and rebound tenderness on the entire abdomen. Her medical history revealed autoimmune hepatitis controlled with oral steroid, osteoporosis, compression fracture of the spine and spinal canal stenosis, chronic kidney dysfunction, fracture of the left hand and femur, pneumonia, temporomandibular joint myelitis, and cesarean birth with median incision at the lower abdomen. Laboratory test revealed elevation of the inflammation reaction values: white blood cell (WBC), 15 700/μL; C-reactive protein (CRP), 24.0 mg/dL. The blood urine nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine values (39.1 and 0.99 mg/dL, respectively) were also elevated. Her urine was purulent and contains rich bacteria (3+) and WBC (3+). Enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed small intestine dilation, and thus, she was admitted to our hospital with a diagnosis of ileus and septic state, with quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment Score of 2 points at non-intensive care unit situation (Fig. 1A). An ileus tube was inserted by transnasal endoscopy (Fig. 1B).

(A) Enhanced abdominal computed tomography on admission showing a dilation of the small intestine (white arrow). The patient was diagnosed with ileus state. (B) X-ray of the abdomen revealed an ileus tube and the central venous catheter inserted from the right femoral vein.

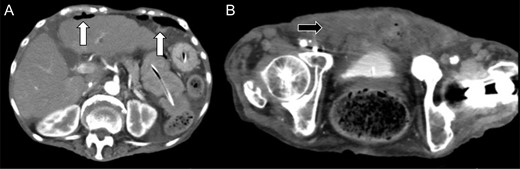

She was given an antibiotic (meropenem 0.5 g, every 8 h), but the next day, the abdominal pain worsened. Laboratory test showed elevation of the inflammation reaction values, and enhanced CT showed free air in the abdominal cavity (Fig. 2A), with increased fluid collection in the anterior space of the bladder (Fig. 2B). We performed emergency laparotomy for suspicion of digestive tract perforation. There was a small hole at the dome of the urinary bladder and another at the peritoneum, and very thick pus extruded into the abdominal cavity. We opened the front part of the urinary bladder, sutured the hole and sutured the bladder to close it. A permanent urinary catheter was placed for bladder drainage and decompression. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the inflammation reaction improved. She was discharged on the 21st postoperative day and had no recurrence since then.

Enhanced abdominal computed tomography 1 day after admission showing (A) free air in the abdominal cavity (white arrow) and (B) massive fluid collection in the posterior space of the urinary bladder (black arrow).

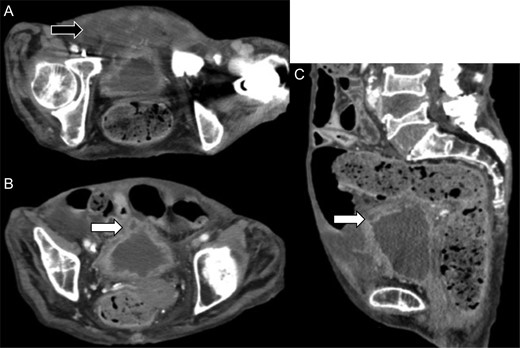

We reviewed the abdominal CT on admission, which revealed a deficit in the urinary bladder wall, with fluid collection around it (Fig. 3). The perforation of the urinary bladder was present on admission, and that of the peritoneum occurred on the following day. Previous magnetic resonance imaging revealed no diverticulum of the urinary bladder or any organic failure.

Review of the enhanced abdominal computed tomography on admission after the operation revealed (A) fluid collection in the posterior space of the urinary bladder (black arrow) and (B and C) deficit in the urinary bladder wall and suspected perforation (white arrow).

DISCUSSION

The cause of urinary bladder rupture is categorized into traumatic and others [1]. Traumatic rupture is responsible for about 96.6% of all cases, and spontaneous rupture is very rare. The symptom of the urinary bladder rupture is abrupt abdominal pain, which usually causes the peritoneal irritation sign, making it difficult to distinguish from perforation of the gastric tract or other gastrointestinal diseases [1]. SRUB is a rare occurrence and is often the result of an underlying pathology [2]. It was not until 1929 that Sisk and Wear [3] first coined the term SRUB, which they defined as follow: ‘If the bladder ruptures without external stimulation, it is spontaneous and deserves to be reported as such.’ Diagnosing SRUB is challenging and is usually only confirmed during laparotomy [4]. The common causes of SRUB are inflammation or infection, neurogenic bladder, urine retention, pelvic irradiation, invasive tumor and idiopathic [5]. The most common inflammatory etiology is of gonorrheal origin, and bacterial cystitis rarely causes SRUB.

The rate of correct diagnosis of urinary rupture is 43.2–52.5%, and many cases have to undergo exploratory laparotomy. This is why that any misdiagnosis is critical and delayed diagnosis also increases complications. The most frequent CT image finding is accumulation of ascitic fluid (93%). Free air, which strongly indicates gastric tract perforation, is seen in 16% of cases, and it makes the preoperative diagnosis difficult [6]. It was the same in our case, and definite diagnosis was only determined after laparotomy. Peters [7] mentioned that the risk of misdiagnosis could be decreased by infusing at least 250 mL of dye during cystography. Laboratory test showed elevation of BUN and creatinine (thus called ‘pseudo-renal failure’), which is seen in almost 45% of cases [8]. This change is caused the reabsorption of the urine that leaked to the intra-abdominal space via the peritoneum, but other acute abdomen cases are also sometimes accompanied with renal failure, making it difficult to diagnose.

The treatment of urinary bladder rupture is drainage of the effused urine, closure of the perforation site, and strong antibiotic therapy. Immediate surgical intervention or others should be done as soon as practicable. In some cases, conservative therapy is acceptable. Richardson et al. [9] mentioned some conditions for conservative therapy, and one of which is absence of infection and prophylactic antibiotic therapy is available. In this case, the bacterial cystitis was so severe, and surgical intervention was desirable. Wheeler [10] mentioned the possibility of rerupture of the thin scar of the postrupture site after conservative therapy and the importance of intermittent urinary catheterization or bladder catheter placement for decompression [10]. In our case, both the diagnosis and the treatment were performed during the operation, and the good postoperative course without rerupture can be attributed to the prompt intervention and proper decompression.

SRUB is rare, and bacterial cystitis rarely causes it; thus, accurate diagnosis and proper intervention are essential.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to declare.

FUNDING

This report did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available and can be reproduced whenever needed. All the procedures performed in the study involving the patient were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution.