-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Zhong Zhang, Wei Yuen Su, Prof Brian Kenneth Owler, Disseminated Mycobacterium abscessus infection with spondylodiscitis of thoracic spine, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2018, Issue 6, June 2018, rjy141, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy141

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A case is presented of an immunosuppressed 51-year-old man with spondylodiscitis of the thoracic vertebrae from Mycobacterium abscessus infection, in context of disseminated multi-systemic infection with pulmonary and gastrointestinal involvement. Multiple challenges in the diagnosis and management of this confounding case are outlined. The patient underwent aggressive surgical debridement via T8–T10 vertebrectomy plus reconstruction, and right hemicolectomy to obtain source control. This was followed by prolonged combination antibiotic therapy. At time of manuscript patient is 10 months post-surgery and 18 months from initial presentation, with excellent surgical outcome and control of the infection. The unique microbiological and clinical characteristics of M. abscessus are briefly outlined. A synopsis of the relevant literature is given highlighting the relative paucity of evidence to aid management of this unpredictable infection. Current best practice guideline recommends combination of medical therapy and aggressive surgical debridement for infections caused by M. abscessus.

INTRODUCTION

Mycobacterium abscessus is an uncommon pathogen in humans. It is classified as a non-tuberculous mycobacterium (NTM) and occurs most frequently as chronic pulmonary infections, followed by soft tissue, ocular and CNS infections [1]. The organism is multidrug resistant and extremely difficult to diagnose and treat. There is limited evidence to guide management. We present a case of disseminated multi-systemic infection with M. abscessus that was successfully treated with combined medical and surgical management, highlighting the unique challenges that this infection may present. A summary of the existing literature is provided.

CASE REPORT

A 51-year-old gentleman of South-East Asian origin presented in mid-2016 with 5 days of fever, cough, shortness of breath and pleuritic chest pain. His history was remarkable only for SAPHO (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteitis) syndrome for which prednisone and methotrexate were commenced a few months prior.

Computerized tomography (CT) demonstrated right lower lobe consolidation and parapneumonic effusion. He was treated with piperacillin/tazobactam and methotrexate ceased. In the subsequent months he represented for recurrence of the same symptoms. CT showed the persisting effusion despite further antibiotic therapy.

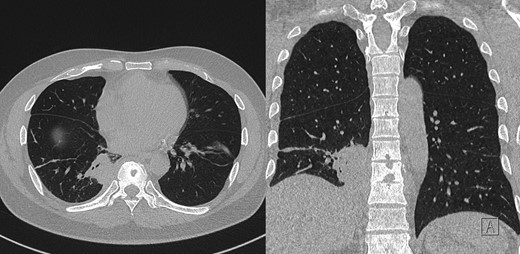

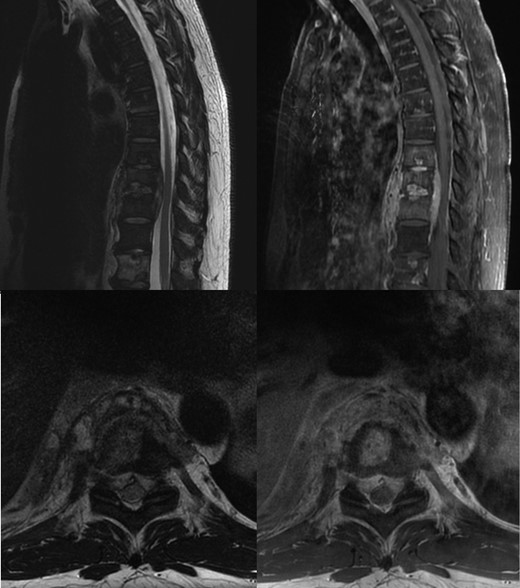

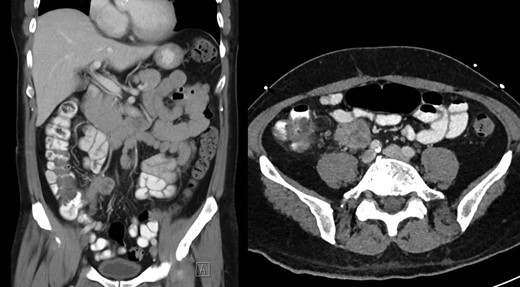

During this period he also developed osteolytic lesions of the T9/10 vertebral bodies immediately adjacent to the effusion (Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was arranged showing T8–T10 spondylodiscitis, prevertebral and epidural phelgmons (Fig. 2), without radiological evidence of spinal cord compression. Further imaging with gallium scan showed no evidence of osteomyelitis elsewhere in the body, but unexpectedly revealed area of increased vascularity in the right iliac fossa suggestive of soft tissue infection. CT abdomen confirmed the lesion to be a peri-appendicular abscess (Fig. 3).

Post-contrast CT chest, showing ostelytic lesion of T9 vertebral body developed since original presentation and imaging. Adjacent to T9 vertebral body is area of persistent parapneumonic effusion.

Non-contrast T2 and post contrast T1 MRI, showing T8–T10 spondylodiscitis, prevertebral and epidural phelgmons, without radiological evidence of spinal cord compression.

Post-contrast CT abdomen, showing peri-appendicular abscess corresponding to area of increased uptake on gallium scan.

Bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage was performed without immediate results available. CT-guided biopsy of the prevertebral phelgmon and disc showed granulomatous inflammation. Empirical treatment for mycobacterium tuberculosis was started on presumption of Pott’s disease. Six weeks later, samples from bronchoscopy and prevertebral phelgmon both yielded M. abscessus.

After extensive discussions of the treatment options a trial of antibiotics was commenced. After 2 months of amikacin, linezolid and tigecycline (azithromycin was discontinued as it lead to prolonged QT interval), side effects of the antibiotics therapy became intolerable despite improvement in MRI findings. Side effects consist of nausea/anorexia with resulting weight loss and malnutrition, painful peripheral neuropathy, and myelosuppression requiring weekly blood transfusions.

In order to treat the ongoing infection he agreed to undergo aggressive surgical debridement. He underwent open thoracotomy, T8–T10 vertebrectomy, reconstruction with expandable cage and posterior percutaneous pedicle screw fixation of T6–T12 (Nuvasive, San Diego, CA). Surgery was undertaken 5 months after initial presentation and 3 months after initiation of antibiotic therapy.

After recovery from the spinal procedure, a right hemicolectomy was carried out with primary anastomosis. A transient chyle leak occurred post thoracotomy and both operations were complicated by minor wound infections. Surgical samples from the vertebrectomy and right hemicolectomy, as well as sample from the thoracotomy site infection all grew M. abscessus, confirming persistent disseminated infection.

At time of manuscript patient is 10 month post-surgery, he remains on antibiotic therapy (15 months of continuous treatment) with low dose tigecycline, bedaquiline, clofazimine and cefoxitin, which are well tolerated. Imaging of the spine at 3 months postoperatively shows early signs of bony fusion, preservation of alignment with no hardware complications (Fig. 4), without progression of infection. Patient remains free of neurological deficit and is ambulating normally without back pain.

X-ray and 3D reconstruction following non contrast CT thoracic spine, showing final hardware position and spinal alignment after T8–T10 vertebrectomy, reconstruction with expandable cage and percutaneous pedicle screw fixation of T6–T12 (Nuvasive, San Diego, CA).

DISCUSSION

Mycobacterium abscessus is a rapidly growing mycobacterium specie, commonly occurring in water, soil, dust, and frequently contaminates medical products. It is loosely grouped along with more well-known organisms such as mycobacterium avium, mycobacterium chelonae and mycobacterium marinum as NTM. It is further subdivided into three subspecies on basis on genomic sequencing: mycobacterium abscessus abscessus, mycobacterium abscessus massiliense and mycobacterium abscessus bolletii. Indirect transmission of the organism occurs by contamination of open wounds, or use of contaminated medical products, with little risk of direct interpersonal transmission. The organism is multidrug resistant and often resistant to standard medical disinfectants. Clinically it is encountered most frequently as chronic pulmonary infections, followed by soft tissue, occular and CNS infections. It can be seen in post-traumatic wound infections and nosocomial infections [1]. It generally requires prolonged culture time prior to positive identification and confirmation of diagnosis. The American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines recommends macrolide based, multidrug regimen for both pulmonary and extra-pulmonary infections, with combination of medical and surgical treatment [2].

There is a paucity of evidence to guide treatment of M. abscessus infections. The Emerging Infections Network [3] reported 65 cases between March to December 2013, of which 41 involved pulmonary infections and 24 extra-pulmonary infections. Pulmonary infections were most commonly treated with combination therapy with amikacin, azithromycin, plus another intravenous agent. The 85% of cases required change in antibiotic therapy due to side effects and median duration of treatment was 12 months with interquartile range of 9–18 months. Extra-pulmonary infections were commonly treated with amikacin, macrolides and imipenem. And 67% of cases required a change in antibiotic therapy, and median duration of treatment was 6 months with interquartile range of 4–8 months.

A Korean case series [4] reported 41 cases of pulmonary infection, median duration of intravenous antibiotics therapy was 230 days (range: 60–601 days), with median duration of total antibiotic therapy 511 days (range: 164–1249 days). They reported a 44% rate of adverse reactions to therapy, with treatment success in 81% of cases (defined as three sets of negative sputum, plus having completed a minimum of 6 months of total treatment or as per treating physicians’ decision).

Evidence to guide the treatment of spinal infections with M. abscessus is even more limited. Five individual case reports of M. abscessus infection of the vertebral column were identified in the literature [5–9], and are summarized in Table 1. Of the five reported cases, three cases required extensive surgical debridement of the infection via vertbrectomy followed by spinal reconstructions. Four cases reported prolonged antibiotic therapy of between 6 and 12 months followed by full recovery of the patient (including all three surgical cases); in the fifth case the patient was lost to follow-up after completing 6 weeks of therapy.

Summary of five case reports of M. abscessus infection of the vertebral column

| Study . | Age, sex . | Cause . | Radiological findings . | Diagnostic sampling . | Culture . | Antibiotic . | Surgery . | Duration of treatment . | Outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kato et al. [5] | 67, F | No identified cause | L1/2 osteomyelitis with epidural phelgmon + prevertebral abscess | CT guided biopsy of abscess | M. abscessus, time to culture not reported | Clarithromycin, Amikacin, Imipenem | Retroperitoneal approach, L1 vertebrectomy, cage reconstruction, iliac crest autograft, anterior T12–L2 instrumented fusion | 3 Months intravenous followed by 6 months of oral therapy | Bony fusion on imaging, symptom free at follow up |

| Edwards et al. [6] | 50, F | Blunt trauma to back (assault) | L4/5 osteomyelitis with epidural phelgmon + prevertebral abscess | CT guided biopsy | M. abscessus after 6 weeks culture | Vanc + Cefepime (empirical) | None | 6 Weeks intravenous therapy | Lost to follow up |

| Chan et al. [7] | 16, F | Blunt trauma to back (skating accident) | T8–10 osteomyelitis, prevertebral phelgmon | Thoracoscopic biopsy of vertebral body | M. abscessus, time to culture not reported | Clarithromycin | None | 6 Months total | Resolution of marrow oedema, C-reactive protein undetectable, symptom free at follow up |

| Sarria et al. [8] | 53, M | Intravenous drug user | L3–5 osteomyelitis and prevertebral abscess | CT guided biopsy of abscess | M. abscessus, time to culture not reported | Amikacin (changed to imipenem), cefoxitin, clarithromycin | Anterior approach, L3–5 vertebrectomy, fibular autograft, posterior T11–S1 instrumented fusion, iliac crest autograft | 12 Months total | Pain free, mobilize with minimum assist at follow up |

| Pruitt et al. [9] | 17, F | Steroid dependent (systemic lupus erythematosus) | T12–L1 osteomyelitis | Unknown | M. abscessus | Amikacin, clarithromycin | Decompression + fusion | 2 Months intravenous followed by 7 months of oral therapy | Recovered |

| Present case | 51, M | Methotrexate and prednisolone for rheumatological condition | T8–T10 spondylodiscitis, prevertebral and epidural phelgmons | CT guided biopsy of disc | M. abscessus after 6 weeks culture | Initially amikacin, linezolid and tigecycline. Changed to tigecycline, bedaquiline, clofazimine and cefoxitin | Thoracotomy, T8–T10 vertebrectomy + reconstruction, pedicle screw fixation of T6–T12 | 15 Months to date | Full functional recovery, mobilizing pain free |

| Study . | Age, sex . | Cause . | Radiological findings . | Diagnostic sampling . | Culture . | Antibiotic . | Surgery . | Duration of treatment . | Outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kato et al. [5] | 67, F | No identified cause | L1/2 osteomyelitis with epidural phelgmon + prevertebral abscess | CT guided biopsy of abscess | M. abscessus, time to culture not reported | Clarithromycin, Amikacin, Imipenem | Retroperitoneal approach, L1 vertebrectomy, cage reconstruction, iliac crest autograft, anterior T12–L2 instrumented fusion | 3 Months intravenous followed by 6 months of oral therapy | Bony fusion on imaging, symptom free at follow up |

| Edwards et al. [6] | 50, F | Blunt trauma to back (assault) | L4/5 osteomyelitis with epidural phelgmon + prevertebral abscess | CT guided biopsy | M. abscessus after 6 weeks culture | Vanc + Cefepime (empirical) | None | 6 Weeks intravenous therapy | Lost to follow up |

| Chan et al. [7] | 16, F | Blunt trauma to back (skating accident) | T8–10 osteomyelitis, prevertebral phelgmon | Thoracoscopic biopsy of vertebral body | M. abscessus, time to culture not reported | Clarithromycin | None | 6 Months total | Resolution of marrow oedema, C-reactive protein undetectable, symptom free at follow up |

| Sarria et al. [8] | 53, M | Intravenous drug user | L3–5 osteomyelitis and prevertebral abscess | CT guided biopsy of abscess | M. abscessus, time to culture not reported | Amikacin (changed to imipenem), cefoxitin, clarithromycin | Anterior approach, L3–5 vertebrectomy, fibular autograft, posterior T11–S1 instrumented fusion, iliac crest autograft | 12 Months total | Pain free, mobilize with minimum assist at follow up |

| Pruitt et al. [9] | 17, F | Steroid dependent (systemic lupus erythematosus) | T12–L1 osteomyelitis | Unknown | M. abscessus | Amikacin, clarithromycin | Decompression + fusion | 2 Months intravenous followed by 7 months of oral therapy | Recovered |

| Present case | 51, M | Methotrexate and prednisolone for rheumatological condition | T8–T10 spondylodiscitis, prevertebral and epidural phelgmons | CT guided biopsy of disc | M. abscessus after 6 weeks culture | Initially amikacin, linezolid and tigecycline. Changed to tigecycline, bedaquiline, clofazimine and cefoxitin | Thoracotomy, T8–T10 vertebrectomy + reconstruction, pedicle screw fixation of T6–T12 | 15 Months to date | Full functional recovery, mobilizing pain free |

Summary of five case reports of M. abscessus infection of the vertebral column

| Study . | Age, sex . | Cause . | Radiological findings . | Diagnostic sampling . | Culture . | Antibiotic . | Surgery . | Duration of treatment . | Outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kato et al. [5] | 67, F | No identified cause | L1/2 osteomyelitis with epidural phelgmon + prevertebral abscess | CT guided biopsy of abscess | M. abscessus, time to culture not reported | Clarithromycin, Amikacin, Imipenem | Retroperitoneal approach, L1 vertebrectomy, cage reconstruction, iliac crest autograft, anterior T12–L2 instrumented fusion | 3 Months intravenous followed by 6 months of oral therapy | Bony fusion on imaging, symptom free at follow up |

| Edwards et al. [6] | 50, F | Blunt trauma to back (assault) | L4/5 osteomyelitis with epidural phelgmon + prevertebral abscess | CT guided biopsy | M. abscessus after 6 weeks culture | Vanc + Cefepime (empirical) | None | 6 Weeks intravenous therapy | Lost to follow up |

| Chan et al. [7] | 16, F | Blunt trauma to back (skating accident) | T8–10 osteomyelitis, prevertebral phelgmon | Thoracoscopic biopsy of vertebral body | M. abscessus, time to culture not reported | Clarithromycin | None | 6 Months total | Resolution of marrow oedema, C-reactive protein undetectable, symptom free at follow up |

| Sarria et al. [8] | 53, M | Intravenous drug user | L3–5 osteomyelitis and prevertebral abscess | CT guided biopsy of abscess | M. abscessus, time to culture not reported | Amikacin (changed to imipenem), cefoxitin, clarithromycin | Anterior approach, L3–5 vertebrectomy, fibular autograft, posterior T11–S1 instrumented fusion, iliac crest autograft | 12 Months total | Pain free, mobilize with minimum assist at follow up |

| Pruitt et al. [9] | 17, F | Steroid dependent (systemic lupus erythematosus) | T12–L1 osteomyelitis | Unknown | M. abscessus | Amikacin, clarithromycin | Decompression + fusion | 2 Months intravenous followed by 7 months of oral therapy | Recovered |

| Present case | 51, M | Methotrexate and prednisolone for rheumatological condition | T8–T10 spondylodiscitis, prevertebral and epidural phelgmons | CT guided biopsy of disc | M. abscessus after 6 weeks culture | Initially amikacin, linezolid and tigecycline. Changed to tigecycline, bedaquiline, clofazimine and cefoxitin | Thoracotomy, T8–T10 vertebrectomy + reconstruction, pedicle screw fixation of T6–T12 | 15 Months to date | Full functional recovery, mobilizing pain free |

| Study . | Age, sex . | Cause . | Radiological findings . | Diagnostic sampling . | Culture . | Antibiotic . | Surgery . | Duration of treatment . | Outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kato et al. [5] | 67, F | No identified cause | L1/2 osteomyelitis with epidural phelgmon + prevertebral abscess | CT guided biopsy of abscess | M. abscessus, time to culture not reported | Clarithromycin, Amikacin, Imipenem | Retroperitoneal approach, L1 vertebrectomy, cage reconstruction, iliac crest autograft, anterior T12–L2 instrumented fusion | 3 Months intravenous followed by 6 months of oral therapy | Bony fusion on imaging, symptom free at follow up |

| Edwards et al. [6] | 50, F | Blunt trauma to back (assault) | L4/5 osteomyelitis with epidural phelgmon + prevertebral abscess | CT guided biopsy | M. abscessus after 6 weeks culture | Vanc + Cefepime (empirical) | None | 6 Weeks intravenous therapy | Lost to follow up |

| Chan et al. [7] | 16, F | Blunt trauma to back (skating accident) | T8–10 osteomyelitis, prevertebral phelgmon | Thoracoscopic biopsy of vertebral body | M. abscessus, time to culture not reported | Clarithromycin | None | 6 Months total | Resolution of marrow oedema, C-reactive protein undetectable, symptom free at follow up |

| Sarria et al. [8] | 53, M | Intravenous drug user | L3–5 osteomyelitis and prevertebral abscess | CT guided biopsy of abscess | M. abscessus, time to culture not reported | Amikacin (changed to imipenem), cefoxitin, clarithromycin | Anterior approach, L3–5 vertebrectomy, fibular autograft, posterior T11–S1 instrumented fusion, iliac crest autograft | 12 Months total | Pain free, mobilize with minimum assist at follow up |

| Pruitt et al. [9] | 17, F | Steroid dependent (systemic lupus erythematosus) | T12–L1 osteomyelitis | Unknown | M. abscessus | Amikacin, clarithromycin | Decompression + fusion | 2 Months intravenous followed by 7 months of oral therapy | Recovered |

| Present case | 51, M | Methotrexate and prednisolone for rheumatological condition | T8–T10 spondylodiscitis, prevertebral and epidural phelgmons | CT guided biopsy of disc | M. abscessus after 6 weeks culture | Initially amikacin, linezolid and tigecycline. Changed to tigecycline, bedaquiline, clofazimine and cefoxitin | Thoracotomy, T8–T10 vertebrectomy + reconstruction, pedicle screw fixation of T6–T12 | 15 Months to date | Full functional recovery, mobilizing pain free |

CONCLUSION

Mycobacterium abscesses is an uncommon cause of vertebral infection. Prolonged time required to culture the organism, plus multiple drug resistances and frequent adverse effects from antibiotics makes it a challenging infection to treat. Soft tissue infections and spinal infections are best managed with combination of medical therapy and aggressive surgical debridement.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the advice and support provided by the Division of Infectious Diseases of the Massachusetts General Hospital in care of the patient.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Dr Zhong Zhang, Dr Wei Yuen Su and Prof Brian Kenneth Owler declare that they have no conflict of interest.