-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Paola Eiben, Sancho Rodriguez-Villar, A case of periorbital necrotizing fasciitis rapidly progressing to severe multiorgan failure, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2018, Issue 4, April 2018, rjy083, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy083

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Periorbital necrotizing fasciitis (PNF) is a severe suppurative infection of the subcutaneous tissue and underlying fascia of the periorbital region. Typically, the course of PNF is milder and has a better prognosis than that of necrotizing fasciitis in other parts of the body. As such, this disease is thought to be associated with a significantly smaller risk of morbidity and mortality. Nevertheless, it is a rare and devastating condition that can lead to disfigurement, blindness and death. Early recognition is critical to improved patient outcomes. Here, we describe a case of PNF in a 60-year-old male that rapidly progressed to widespread systemic involvement and severe multiorgan failure requiring ventilatory, cardiovascular and renal support. Treatment included broad-spectrum antibiotics, intravenous immunoglobulin and surgical debridement. This case highlights the life-threatening nature of PNF, as demonstrated by rapid progression to multiorgan dysfunction and the need of an urgent surgical intervention.

INTRODUCTION

Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) is a fulminant life-threatening infection that affects the skin and subcutaneous tissue. It is characterized by rapidly spreading necrosis that tracks along the superficial fascial plane. Most commonly NF develops in areas of compromised skin-integrity (e.g. following surgery or trauma) which allows for microbial invasion, however, it can also occur in unspoiled tissue. Other risk factors include immunocompromise and co-existence of systemic disease such as diabetes mellitus. Typical presentation involves severe pain disproportionate to the apparent area involved, erythema, oedema and raised temperature. This is associated with a rapid progression and deterioration. Diagnosis is often difficult, requiring a high level of suspicion, as clinical signs fail to denote the severity of the condition.

NF can be classified into four subtypes depending on the causative pathogen: type I is the most prevalent (70–80% of cases) and is polymicrobial in origin; type II is due to monomicrobial infection with group A Streptococcus alone or in association with Staphylococcus aureus; type III is due to infection with Clostridium species or gram-negative bacteria; type IV is due to fungi.

Morbidity and mortality of NF are high but vary between bodily regions. Periorbital NF (PNF) is a rare form of NF with UK incidence of 0.24 per 1 000 000 per year [1]. It is generally thought to be the least severe form of NF with the best prognosis [2]. Multiorgan involvement is uncommon. Lower rates of morbidity and mortality are related to earlier presentation and diagnosis, higher vascularity of the region leading to improved antimicrobial agent penetration, and anatomical structure with the orbital septum hindering posterior progression [2].

Although rare, and often associated with a milder clinical course than NF in the extremities, abdomen or perineum, PNF can lead to severe complications. Here we describe a case when PNF rapidly progressed to septic shock and multiorgan failure.

CASE REPORT

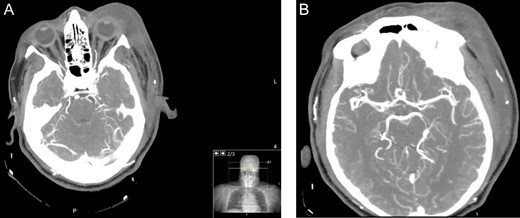

A 60-year-old male with a past medical history of hypertension presented to the emergency department of a District General Hospital with a 7-day history of a worsening left eye swelling, pain and erythema. There was no history of previous trauma, sinus disease or recent surgery. On arrival, clinical examination revealed that the patient was in circulatory shock with signs of sepsis. Immediate treatment for a suspected septic shock due to left periorbital cellulitis was started with broad-spectrum intravenous (IV) antibiotics (Vancomycin, Gentamycin, Meropenem and Clindamycin), aggressive fluid resuscitation and oxygen supplementation. A computed tomography (CT) carotid angiogram revealed a diffuse left orbital cellulitis with no intraorbital collection (Fig. 1A). There was no evidence of intracerebral vascular thrombosis (Fig. 1B). Blood tests showed an inflammatory picture (Table 1).

Axial CT angiogram carotids images showing (A) diffuse left periorbital region involvement with no retro-orbital or extra-orbital collections. (B) No evidence of vessel thrombosis.

| Days of hospital admission . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 10 . | 15 . | 19 . | 3 months . |

| CRP (mg/l) | 560 | 390 | 384.5 | 212.7 | 95.4 | 35.5 | 13.8 | 4.9 | <0.2 |

| WBC (11^9/l) | 19.80 | 16.57 | 18.98 | 18.35 | 27.33 | 22.63 | 10.08 | 7.12 | 13.02 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 18.60 | 14.91 | 17.04 | 15.40 | 20.22 | 17.29 | 6.33 | 3.35 | 6.61 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 0.70 | 0.75 | 1.23 | 1.71 | 4.37 | 3.96 | 2.98 | 3.03 | 5.68 |

| Hb (g/l) | 154 | 102 | 95 | 90 | 96 | 87 | 75 | 75 | 133 |

| Creatinine (umol/l) | 792 | 711 | 379 | 320 | 324 | 192 | 298 | 221 | 109 |

| K+ (mmol/l) | 3.7 | 4.2 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.7 | 5.3 | 4.8 | 4.4 |

| Blood glucose (mmol/l) | 7.1 | 10.3 | 8.9 | 7.1 | 7.7 | 5.3 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Days of hospital admission . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 10 . | 15 . | 19 . | 3 months . |

| CRP (mg/l) | 560 | 390 | 384.5 | 212.7 | 95.4 | 35.5 | 13.8 | 4.9 | <0.2 |

| WBC (11^9/l) | 19.80 | 16.57 | 18.98 | 18.35 | 27.33 | 22.63 | 10.08 | 7.12 | 13.02 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 18.60 | 14.91 | 17.04 | 15.40 | 20.22 | 17.29 | 6.33 | 3.35 | 6.61 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 0.70 | 0.75 | 1.23 | 1.71 | 4.37 | 3.96 | 2.98 | 3.03 | 5.68 |

| Hb (g/l) | 154 | 102 | 95 | 90 | 96 | 87 | 75 | 75 | 133 |

| Creatinine (umol/l) | 792 | 711 | 379 | 320 | 324 | 192 | 298 | 221 | 109 |

| K+ (mmol/l) | 3.7 | 4.2 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.7 | 5.3 | 4.8 | 4.4 |

| Blood glucose (mmol/l) | 7.1 | 10.3 | 8.9 | 7.1 | 7.7 | 5.3 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Days of hospital admission . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 10 . | 15 . | 19 . | 3 months . |

| CRP (mg/l) | 560 | 390 | 384.5 | 212.7 | 95.4 | 35.5 | 13.8 | 4.9 | <0.2 |

| WBC (11^9/l) | 19.80 | 16.57 | 18.98 | 18.35 | 27.33 | 22.63 | 10.08 | 7.12 | 13.02 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 18.60 | 14.91 | 17.04 | 15.40 | 20.22 | 17.29 | 6.33 | 3.35 | 6.61 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 0.70 | 0.75 | 1.23 | 1.71 | 4.37 | 3.96 | 2.98 | 3.03 | 5.68 |

| Hb (g/l) | 154 | 102 | 95 | 90 | 96 | 87 | 75 | 75 | 133 |

| Creatinine (umol/l) | 792 | 711 | 379 | 320 | 324 | 192 | 298 | 221 | 109 |

| K+ (mmol/l) | 3.7 | 4.2 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.7 | 5.3 | 4.8 | 4.4 |

| Blood glucose (mmol/l) | 7.1 | 10.3 | 8.9 | 7.1 | 7.7 | 5.3 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Days of hospital admission . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 10 . | 15 . | 19 . | 3 months . |

| CRP (mg/l) | 560 | 390 | 384.5 | 212.7 | 95.4 | 35.5 | 13.8 | 4.9 | <0.2 |

| WBC (11^9/l) | 19.80 | 16.57 | 18.98 | 18.35 | 27.33 | 22.63 | 10.08 | 7.12 | 13.02 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 18.60 | 14.91 | 17.04 | 15.40 | 20.22 | 17.29 | 6.33 | 3.35 | 6.61 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 0.70 | 0.75 | 1.23 | 1.71 | 4.37 | 3.96 | 2.98 | 3.03 | 5.68 |

| Hb (g/l) | 154 | 102 | 95 | 90 | 96 | 87 | 75 | 75 | 133 |

| Creatinine (umol/l) | 792 | 711 | 379 | 320 | 324 | 192 | 298 | 221 | 109 |

| K+ (mmol/l) | 3.7 | 4.2 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.7 | 5.3 | 4.8 | 4.4 |

| Blood glucose (mmol/l) | 7.1 | 10.3 | 8.9 | 7.1 | 7.7 | 5.3 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Despite initial treatment, the patient continued to rapidly deteriorate. A few hours after presentation, he developed respiratory compromise and haemodynamic instability. He was intubated for ventilatory support and vasopressor treatment was commenced. Due to the acute progression to multiorgan failure, PNF was suspected (Figs 2 and 3). The patient was started on intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) and emergency transferred to a specialist centre for surgical intervention. Pre-procedure ophthalmology examination revealed left periorbital swelling, with necrosis of the upper eyelid and a suspected abscess of the lower eyelid. The patient underwent debridement of the upper and lower eyelids and periorbital tissues, with the affected tissue removed back to bleeding edges. Intra-operative findings were consistent with NF.

(A) An image of the patient post-intubation demonstrating marked left periorbital oedema and violaceous erythematous and necrotic changes. (B) A close-up of the left periorbital region skin changes.

Lateral views demonstrating extension of the swelling over the lateral aspect of the face (A) and scalp (B). Purulent material can be seen weeping from the tissue.

Post-operatively, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit for management of septic shock and multiorgan failure secondary to PNF. Initially, he required respiratory support, vasopressors and inotropes for cardiovascular compromise, and renal replacement therapy for acute kidney injury. Following microbiology advice, antibiotics were changed to Meropenem, Clindamycin, Ceftriaxone and Linezolid. Beta-haemolytic Group A Streptococcus (invasive group A streptococcus, IGAS) was isolated from blood cultures and tissue swabs (Table 2).

| Days of hospital admission . | Site . | Cultured organism . | Sensitivity . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Left eye swabs | Staphylococcus Aureus | Penicillin, erythromycin, trimethoprim, gentamycin, flucloxacillin |

| Beta-Haemolytic Group A Streptococcus | Penicillin, erythromycin, first generation cephalosporin, chloramphenicol, clarithromycin | ||

| 1 | Blood cultures | Beta-Haemolytic Group A Streptococcus | Penicillin |

| Days of hospital admission . | Site . | Cultured organism . | Sensitivity . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Left eye swabs | Staphylococcus Aureus | Penicillin, erythromycin, trimethoprim, gentamycin, flucloxacillin |

| Beta-Haemolytic Group A Streptococcus | Penicillin, erythromycin, first generation cephalosporin, chloramphenicol, clarithromycin | ||

| 1 | Blood cultures | Beta-Haemolytic Group A Streptococcus | Penicillin |

| Days of hospital admission . | Site . | Cultured organism . | Sensitivity . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Left eye swabs | Staphylococcus Aureus | Penicillin, erythromycin, trimethoprim, gentamycin, flucloxacillin |

| Beta-Haemolytic Group A Streptococcus | Penicillin, erythromycin, first generation cephalosporin, chloramphenicol, clarithromycin | ||

| 1 | Blood cultures | Beta-Haemolytic Group A Streptococcus | Penicillin |

| Days of hospital admission . | Site . | Cultured organism . | Sensitivity . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Left eye swabs | Staphylococcus Aureus | Penicillin, erythromycin, trimethoprim, gentamycin, flucloxacillin |

| Beta-Haemolytic Group A Streptococcus | Penicillin, erythromycin, first generation cephalosporin, chloramphenicol, clarithromycin | ||

| 1 | Blood cultures | Beta-Haemolytic Group A Streptococcus | Penicillin |

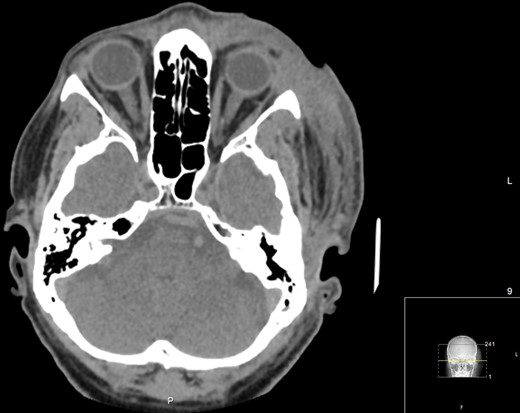

The patient’s condition began to stabilize 24 hours after the surgical intervention. A repeat CT orbit revealed persistent, though reduced, soft tissue swelling with no orbital breach or collections (Fig. 4). The patient improved and was discharged from hospital 19 days after admission. At 3 months, the wounds had healed and there was no visual deficit (Fig. 5). He is awaiting reconstructive surgery under the maxillofacial and the oculoplastic teams.

Axial CT Orbits performed on Day 7 post-debridement, showing improved left periorbital soft tissue swelling. No post-septal involvement, orbit breach or identifiable collections.

An image 3 months post-surgery showing good wound healing and a residual ectropion on the left upper eyelid.

DISCUSSION

NF of the head and neck region can develop secondary to penetrating or blunt trauma, dermatologic infection or pruritus, otologic infection, salivary gland infection, cervical adenitis or peritonsillar abscess [3]. Interestingly, no precipitating factor is found in about 30% of cases [4]. Necrosis develops as a consequence of pathogenic invasion and polymorphonuclear leucocyte infiltration leading to vascular thrombosis and ischaemia with subsequent gangrene of the subcutaneous fat and dermis.

The thinness of the skin and a relative lack of subcutaneous tissue in the periorbital region mean that the necrosis occurs quicker than in other parts of the body with gangrene present as early as 24 hours. The most common type of PNF is NF type II [5].

Complications occur in over 66% of cases of PNF with mortality of 10% [1]. Comparatively, mortality of NF on average ranges between 20% and 35% [4, 6], but has been cited as high as 76% [7]. While the risk of septic shock in PNF is about 20%, it is twice as high in NF elsewhere in the body [2]. To further illustrate the presumed difference in severity between PNF and NF, some case reports describe successful management of PNF with medical management alone [2, 8, 9]. Despite the apparent milder nature of PNF, as demonstrated by the described above case, it is associated with serious complications and should be managed as a life-threatening condition.

Visual loss occurs in over 13% of patients [8] and is attributable to orbital spread, corneal perforation or central retinal artery occlusion. Other complications include vascular thrombosis, facial disfigurement, and functional defects. The most common causes of death are septic shock and multiorgan failure.

Management involves aggressive antimicrobial treatment and surgical debridement of the necrotic tissue. Notably, vessel thrombosis around the affected site means that intravenous antimicrobial treatment may not be able to reach the tissue reducing its effectiveness. Surgical excision mechanically decreases the number of organisms and reduces toxin load.

Although alternative therapies such as hyperbaric oxygen therapy, negative pressure wound therapy or IVIg have been suggested as adjuncts, their use is controversial. Despite contrasting evidence, it is a general belief that IVIg is beneficial in severe NF. IVIg is an immunomodulator with anti-inflammatory properties that among others, facilitates antibody-mediated neutralization of bacterial superantigens and toxins [10]. Our patient was treated with IVIg and we can report positive outcomes.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.