-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Matthew Ho, Jeremy Wu, Brian Skinnider, Alex Kavanagh, Prostatic malakoplakia: a case report with review of the literature, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2018, Issue 3, March 2018, rjy050, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy050

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Prostatic malakoplakia is a rare benign tumor with few reported cases in the literature. A 61-year-old male with a history of Escherichia coli urinary tract infection (UTI) and gross hematuria presented for evaluation with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level of 16.0 ng/mL and a 1.5 cm palpable prostatic nodule highly suggestive of prostate cancer. Cystoscopy was unremarkable. Transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy was performed. Pathologic analysis demonstrated prostatic malakoplakia without evidence of associated malignancy. The patient remains on surveillance with regular physical examination and PSA serum testing. Prostatic malakoplakia is a rare diagnosis with clinical examination findings highly suggestive of prostate cancer and without known associated malignancy risk.

INTRODUCTION

Malakoplakia is a rare condition believed to occur secondary to impaired host response to infection [1, 2]. It primarily occurs in the genitourinary tract, with prostatic manifestation being extremely uncommon [3]. In the prostate, malakoplakia can be a convincing mimic of malignancy, with clinical and imaging characteristics being very similar between the two [1–3].

CASE REPORT

A 61-year-old Chinese male presented for evaluation to the emergency department with new onset dysuria in the setting of chronic irritative voiding symptoms. Urine culture demonstrated evidence of Escherichia coli urinary tract infection (UTI) for which he received culture specific antibiotics. Shortly after completion of this course of antibiotics, the patient experienced 48 h of gross, painless hematuria without additional voiding symptoms. Urologic consultation was requested for further investigation.

On presentation the gentleman had no further specific voiding complaints. He denied constitutional symptoms including fever, weight loss or night sweats. His past medical history was non-contributory and he denied any family history of genitourinary malignancy. Physical examination revealed a palpable 1.5 cm nodule in the left mid-gland of the prostate. Cystoscopy was unremarkable and post-void residual volume was negligible.

The patient’s serum PSA was found to be elevated at 16.0 μg/L. His urine cytology was negative for malignant cells. CT urogram revealed no abnormal upper urinary tract findings.

Based on the physical examination and PSA measurement, the decision was made to pursue transrectal prostate biopsy. The ultrasound revealed a 2 cm hypoechoic lesion on the peripheral aspect of the left lobe of the gland. A total of ten cores were obtained according to standard template prostate biopsy.

PATHOLOGIC ANALYSIS

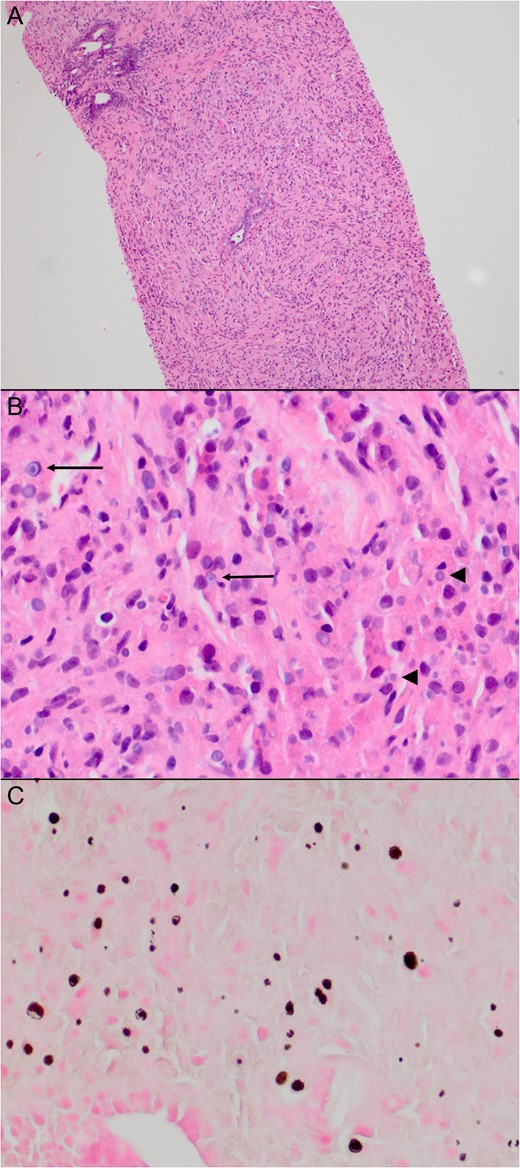

All five cores obtained from the left lobe showed dense inflammatory infiltrate consisting mainly of histiocytes and scattered, atrophic prostatic glands. Noted were Michaelis-Gutmann bodies, which are basophilic cytoplasmic inclusions with a targetoid appearance (Fig. 1). These specimens were diagnosed as malakoplakia, and all cores were negative for malignancy.

Histology of patient’s biopsy specimen. Histology of the biopsies from the left side of the prostate showed a dense inflammatory infiltrate consisting mainly of histiocytes and scattered atrophic prostatic glands (A). Many of the histiocytes contained basophilic cytoplasmic inclusions (B, arrowheads), some with a targetoid appearance (B, arrows), characteristic of Michaelis–Gutmann bodies. These are highlighted on a von Kossa stain (C).

DISCUSSION

The first documented case of malakoplakia was originally described from a bladder biopsy specimen by Michaelis and Gutmann [4]. Grossly it appeared as a soft, yellow plaque, while under microscopy, they noted a granulomatous inflammatory process with small cystoplasmic basophilic inclusions. These concentrically laminated inclusions were named Michaelis–Gutmann bodies (Fig. 1B and C), and are pathognomonic for malakoplakia.

Malakoplakia is a rare diagnosis, with fewer than 1000 cases in the USA per year [1]. Approximately 70% of cases are found in the bladder [3], although cases have been reported in the upper tracts, testes and adnexae [5]. Prostatic malakoplakia is rarer still, with only ~50 cases reported in the literature [3]. The etiology of malakoplakia is incompletely understood, but it is believed to be caused by an impaired histiocytic response against bacteria [1, 2]. It has been found to be more common in patients with either a primary or acquired immunodeficiency such as diabetes, malignancy or HIV/AIDS [2, 3]. Diagnosis of malakoplakia is strongly associated with a documented history of UTI, with E. coli being found in ~80% of these cases [3].

Malakoplakia of the prostate is significant because of its ability to mimic prostate malignancy. In our review of the literature, men diagnosed with malakoplakia typically present with obstructive LUTS, a history of UTI, an abnormal DRE or an elevated PSA level. Physical examination typically reveals hard nodules or masses [2, 3, 5]. As demonstrated by the case which we report, it can be difficult to clinically differentiate malakoplakia from cancer. A history of UTI may raise suspicion of malakoplakia, but this is not specific.

Imaging has similar difficulties discerning malakoplakia from malignancy. As documented in the literature, transrectal ultrasound of malakoplakia shows hypoechoic lesions [1, 6], which are consistent with the sonographic appearance of prostate cancer. This corresponds to the findings reported in the subject of this article. Magnetic resonance imaging, which is a powerful tool in the evaluation of prostatic pathology, fails to differentiate between the two, as reported by Dale et al. [7]. To date, the definitive diagnosis of malakoplakia requires histopathological examination, which is problematic because it can lead to unnecessary prostate biopsies.

It is important to note that prostate cancer and malakoplakia are not exclusive diagnoses. There have been nine reported cases of associated malakoplakia and prostate adenocarcinoma [3, 7], although in these reports, the two types of pathology have not always occurred concurrently. In fact, Medlicott et al. [3] and Guner et al. [8] posit that malakoplakia is a possible complication of prostate biopsy, presumably as a result of infection following the biopsy.

There is no consensus on optimal management of prostatic malakoplakia, likely owing to the paucity of cases. The literature describes treatment with antibiotics aimed at resolution of voiding symptoms, with the preferred agents being fluoroquinolones and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole. Transurethral or even open resection of the prostate is suggested as an option should antimicrobials fail [1, 5, 9, 10]. In the case of our patient, symptoms resolved with initial antibiotic therapy, but malakoplakia was still found on subsequent biopsy. This raises the question of how best to follow the patient with malakoplakia, as symptomatic resolution does not imply pathological resolution. Unfortunately, there is minimal guidance from the literature regarding this issue. We suggest that symptomatic treatment is sufficient and no specific investigations are required in follow-up.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.