-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Keita Kouzu, Yoshiki Kajiwara, Suefumi Aosasa, Yusuke Ishibashi, Keisuke Yonemura, Koichi Okamoto, Eiji Shinto, Hironori Tsujimoto, Kazuo Hase, Hideki Ueno, Hepatic portal venous gas related to appendicitis, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2018, Issue 12, December 2018, rjy333, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy333

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Background: Hepatic portal venous gas (HPVG) is rare with high mortality. There are few reports on HPVG’s association with appendicitis. Here we report a case of HPVG associated with appendicitis. Case presentation: A 79-year-old man presented with acute abdominal pain. Physical examination suggested peritoneal irritation. Blood tests indicated acute inflammation, metabolic acidosis, renal dysfunction and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography revealed HPVG, a contrast defect in the small intestine, and minor ascites around the intestine. Urgent laparotomy was performed as intestinal ischemia was suspected. There were no findings of intestinal ischemia, but the appendix was discolored with wall thickening. We confirmed a clinical diagnosis of peritonitis caused by gangrenous appendicitis. We performed appendectomy and abdominal drainage. After surgery, the patient needed intensive care for septic shock. He left the ICU 7 days after the surgery and was discharged 10 days later. Conclusion: Thus, appendicitis may cause HPVG.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatic portal venous gas (HPVG) is a pathological condition first reported by Wolfe and Evans [1]. It is a relatively rare condition regarded as involving the existence of gas in the portal vein and its branches [2]. The presence of HPVG suggests that the patient might be in a serious clinical condition. It is often observed in cases with intestinal necrosis, such as acute superior mesenteric artery occlusion, which is associated with poor prognosis. Various other causes of HPVG have been reported with the improvement of imaging technology. Here, we report a case of appendicitis associated with HPVG.

CASE REPORT

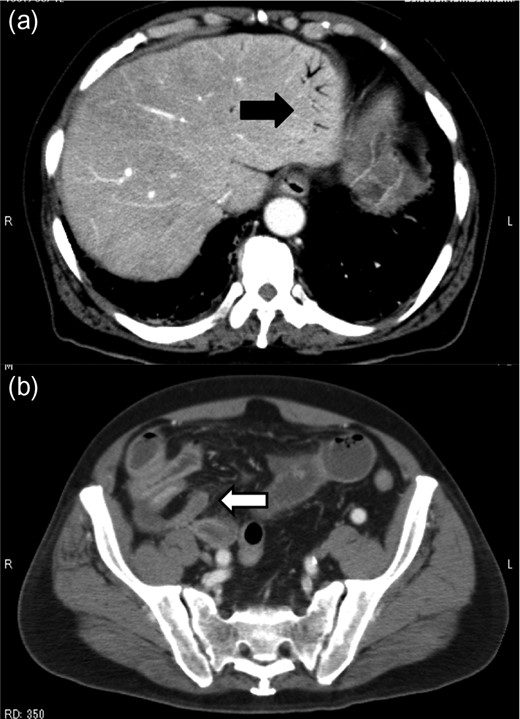

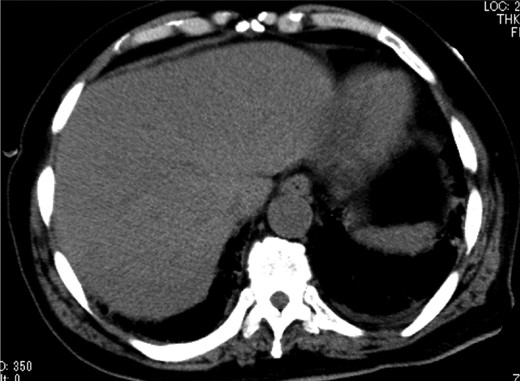

A 79-year-old man with acute abdominal pain had gone to a nearby hospital. As HPVG was detected by abdominal computed tomography (CT), he was transferred to our hospital for further examination and treatment. He had no remarkable past medical history. When he arrived at our hospital, his vital signs were relatively stable (body temperature: 37.2°C; blood pressure: 112/74 mmHg; pulse rate: 68 beats/min). However, physical examination revealed abdominal distention, rebound tenderness and abdominal guarding as signs of peritoneal irritation. The laboratory findings indicated acute inflammation (white blood cell count of 18 400/μL and Creactive protein concentration of 17.7 mg/dL), dehydration and metabolic acidosis (a level of base excess of −7.0 mmol/L). Creatine kinase was remarkably elevated (28 327 IU/L) (Table 1). Plain abdominal radiographs showed distention of the small intestine and suggested subileus (Fig. 1). Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT revealed HPVG (Fig. 2a), a contrast defect in a region of the small intestine, and a small amount of ascites around the intestine. There was no thrombus in any artery; however, the wall of the appendix was moderately thickened when we reevaluated the images retrospectively (Fig. 2b). We performed an urgent laparotomy with the diagnosis of generalized peritonitis caused by intestinal necrosis. A small amount of turbid ascites and a dilated small intestine were observed in the peritoneal cavity. Although the entirety of the small intestine and colon were explored, no intestinal ischemia was detected. Then, we found discoloration of the appendix with wall thickening. We thus made a clinical diagnosis of peritonitis caused by gangrenous appendicitis. Although the appendix wall was fragile, no macroscopic perforation of it was observed. We performed appendectomy and abdominal drainage. Based on the pathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with gangrenous appendicitis, with no evidence of malignancy (Fig. 3). Escherichia coli was positive in the ascitic culture. After the surgery, intravenous antibiotic treatment (meropenem) was administered. The patient subsequently went into septic shock with disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). He was therefore admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), where he received blood purification therapy. The CT images on Day 7 after the surgery showed that HPVG had disappeared (Fig. 4). He left the ICU 7 days after the surgery and was discharged from the hospital another 10 days later.

| Total bilirubin | 0.8 | mg/dL | White blood cell | 18 400/uL |

| AST | 521 | IU/L | Hemoglobin | 15.1g/dL |

| ALT | 154 | IU/L | Hematocrit | 42.9% |

| Total protein | 6.2 | g/dL | Platelets | 7.4 x 104/uL |

| Albumin | 3.1 | g/dL | pH | 7.425 |

| Blood sugar | 75 | mg/dL | PaCO2 | 23.4mmHg |

| Amylase | 308 | IU/L | PaO2 | 84.6mmHg |

| BUN | 38 | mg/dL | HCO3 | 15.1mmol/L |

| Creatinine | 3.16 | mg/dL | Base excess | −7.0mmol/L |

| CK | 28 327 | IU/L | lactic acid | 20mg/dL |

| Na | 135 | mmol/L | PT-INR | 1.14 |

| K | 4.5 | mmol/L | APTT | 51.8s (INR) |

| Cl | 97 | mmol/L | FDP | 250ug/mL |

| CRP | 17.7 | mg/dL | D-dimer | 65.5ug/mL |

| Total bilirubin | 0.8 | mg/dL | White blood cell | 18 400/uL |

| AST | 521 | IU/L | Hemoglobin | 15.1g/dL |

| ALT | 154 | IU/L | Hematocrit | 42.9% |

| Total protein | 6.2 | g/dL | Platelets | 7.4 x 104/uL |

| Albumin | 3.1 | g/dL | pH | 7.425 |

| Blood sugar | 75 | mg/dL | PaCO2 | 23.4mmHg |

| Amylase | 308 | IU/L | PaO2 | 84.6mmHg |

| BUN | 38 | mg/dL | HCO3 | 15.1mmol/L |

| Creatinine | 3.16 | mg/dL | Base excess | −7.0mmol/L |

| CK | 28 327 | IU/L | lactic acid | 20mg/dL |

| Na | 135 | mmol/L | PT-INR | 1.14 |

| K | 4.5 | mmol/L | APTT | 51.8s (INR) |

| Cl | 97 | mmol/L | FDP | 250ug/mL |

| CRP | 17.7 | mg/dL | D-dimer | 65.5ug/mL |

HPVG: hepatic portal venous gas, DIC: disseminated intravascular coagulation, AST: aspartate aminotransferase, ALT: alanine aminotransferase, BUN: blood urea nitrogen, CK: creatine kinase, PT: prothrombin time, APTT: activated partial thromboplastin time, FDP: fibrin degradation product, INR: international normalized ratio.

| Total bilirubin | 0.8 | mg/dL | White blood cell | 18 400/uL |

| AST | 521 | IU/L | Hemoglobin | 15.1g/dL |

| ALT | 154 | IU/L | Hematocrit | 42.9% |

| Total protein | 6.2 | g/dL | Platelets | 7.4 x 104/uL |

| Albumin | 3.1 | g/dL | pH | 7.425 |

| Blood sugar | 75 | mg/dL | PaCO2 | 23.4mmHg |

| Amylase | 308 | IU/L | PaO2 | 84.6mmHg |

| BUN | 38 | mg/dL | HCO3 | 15.1mmol/L |

| Creatinine | 3.16 | mg/dL | Base excess | −7.0mmol/L |

| CK | 28 327 | IU/L | lactic acid | 20mg/dL |

| Na | 135 | mmol/L | PT-INR | 1.14 |

| K | 4.5 | mmol/L | APTT | 51.8s (INR) |

| Cl | 97 | mmol/L | FDP | 250ug/mL |

| CRP | 17.7 | mg/dL | D-dimer | 65.5ug/mL |

| Total bilirubin | 0.8 | mg/dL | White blood cell | 18 400/uL |

| AST | 521 | IU/L | Hemoglobin | 15.1g/dL |

| ALT | 154 | IU/L | Hematocrit | 42.9% |

| Total protein | 6.2 | g/dL | Platelets | 7.4 x 104/uL |

| Albumin | 3.1 | g/dL | pH | 7.425 |

| Blood sugar | 75 | mg/dL | PaCO2 | 23.4mmHg |

| Amylase | 308 | IU/L | PaO2 | 84.6mmHg |

| BUN | 38 | mg/dL | HCO3 | 15.1mmol/L |

| Creatinine | 3.16 | mg/dL | Base excess | −7.0mmol/L |

| CK | 28 327 | IU/L | lactic acid | 20mg/dL |

| Na | 135 | mmol/L | PT-INR | 1.14 |

| K | 4.5 | mmol/L | APTT | 51.8s (INR) |

| Cl | 97 | mmol/L | FDP | 250ug/mL |

| CRP | 17.7 | mg/dL | D-dimer | 65.5ug/mL |

HPVG: hepatic portal venous gas, DIC: disseminated intravascular coagulation, AST: aspartate aminotransferase, ALT: alanine aminotransferase, BUN: blood urea nitrogen, CK: creatine kinase, PT: prothrombin time, APTT: activated partial thromboplastin time, FDP: fibrin degradation product, INR: international normalized ratio.

Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT revealed HPVG (a, black arrow) and thickening of the appendix (b, white arrow).

Gross pathology of the gangrenous appendicitis. Although the appendix wall was markedly thickened and fragile, no macroscopic perforation was observed.

Abdominal CT on Day 7 after the surgery showed that HPVG had disappeared.

DISCUSSION

HPVG is an imaging finding associated with a poor prognosis. The mortality of patients with HPVG in the 1970s was reported to be 75% [3]. In recent years, owing to the increased use of high-resolution CT, earlier diagnosis of HPVG in mild cases has been increasing [4]. However, although the mortality rate of HPVG has dropped to 39%, that associated with bowel necrosis remains at 75% [5].

Abdominal diseases other than intestinal necrosis, such as intraperitoneal abscess, gastric ulcer, inflammatory bowel disease, acute enteritis, and bowel obstruction, can also cause HPVG [6]. As for appendicitis, there are a few reports of cases of it accompanied by HPVG [7, 8]. However, in these cases, HPVG was caused by gangrenous appendix, and there were no reports with a clear description of HPVG without perforation, to the best of our knowledge.

The pathogenesis of HPVG remains controversial. Three major explanations have been proposed: failure of the mucosal defense mechanism due to mucosal disorder, increased intraluminal pressure, and involvement of gas-producing bacteria [3]. In our case, the intraluminal pressure of the small intestine had increased in association with preoperative subileus. Gas-producing bacteria were detected on neither bacterial culture nor pathological examination of the resected surgical specimen.

While non-lethal cases can be conservatively treated, it is difficult to distinguish between non-lethal cases of HPVG and cases requiring surgery. The advance of CT is increasing the opportunities to recognize HPVG with a mild general condition. Some algorithms for managing HPVG including mild cases have been proposed [4, 9]. Our patient required an emergency operation because of the existence of HPVG with peritonitis. Yamadera et al. [10] described the usefulness of laparoscopic intervention. However, it should be limited to cases with no signs of peritoneal irritation and no unstable physical conditions. In our case, laparotomy was selected due to peritonitis and DIC. As HPVG is associated with various diseases, the surgical indication and surgical procedure should be comprehensively decided from the abdominal findings, blood tests, and imaging findings.

In conclusion, it is important to know that appendicitis may cause HPVG, and cases with HPVG with abdominal symptoms leading to generalized peritonitis should undergo an urgent operation.

REFERENCES

- ascites

- gastrointestinal tract vascular insufficiency

- acute abdomen

- appendicitis

- acute abdominal pain

- septic shock

- blood tests

- appendectomy

- physical examination

- disseminated intravascular coagulation

- metabolic acidosis

- kidney failure

- gangrene

- intensive care

- intensive care unit

- intestine, small

- intestines

- laparotomy

- peritonitis

- surgical procedures, operative

- abdomen

- mortality

- peritoneum

- surgery specialty

- inflammation, acute

- abdominal ct

- portal venous gas

- clinical diagnosis