-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ankit P Patel, James L Peacock, Peter A Prieto, High-grade angiosarcoma presenting with cytology-negative hemorrhagic ascites, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2018, Issue 10, October 2018, rjy273, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy273

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Angiosarcomas are a rare subtype of soft-tissue sarcomas originating from the vascular endothelium. Both retroperitoneal and omental angiosarcomas tend to be aggressive and rapidly fatal if not amenable to early intervention. In this report, we describe an unusual case of high-grade angiosarcoma with cytology-negative hemorrhagic ascites and diffuse omental invasion. Multiple investigations into the origin of the hemorrhagic ascites, including cytological analysis, tumor marker measurements, serum-ascites albumin gradient calculation and frozen section pathological examination, failed to reveal a diagnosis. We conclude that malignancy should be considered in the differential diagnosis in the presence of suspicious cytology-negative hemorrhagic ascites and concomitant retroperitoneal and abdominal findings.

INTRODUCTION

Angiosarcomas are a rare subtype of soft-tissue sarcomas originating from vascular endothelium. They comprise <4% incidence over 20 years for all soft-tissue sarcomas [1]. Angiosarcomas typically have an indolent presentation. However, they can present with a spectrum of symptoms ranging from chronic discomfort to acute complications such as the development of hemorrhage. In this report, we describe an unusual case of a retroperitoneal angiosarcoma presenting as idiopathic hemorrhagic ascites.

CASE REPORT

A 69-year-old Caucasian male was admitted with a 2-day history of worsening abdominal pain associated with nausea. His background history was significant for atrial fibrillation, diabetes, chronic kidney disease and left thoracotomy for lung cancer resection.

Two weeks prior to admission, he presented to a urology clinic for evaluation of micropenis and was incidentally noted to have microhematuria on urinalysis. He underwent a negative cystoscopy. He proceeded to have a computerized tomography (CT) scan that revealed a left perinephric mass with enlarged peri-renal and para-aortic lymph nodes, as well as retroperitoneal streaky changes (Fig. 1). Due to concern for malignancy, he underwent a CT-guided peri-renal lesion biopsy. Initial histopathological analysis revealed extensive areas of atypical cellular proliferation with no clear pathological diagnosis. The patient elected surveillance rather than surgical exploration.

CT scan demonstrates a fluid collection posterior and inferior to the left kidney extensive infiltrative changes extending inferiorly into the pelvis. There is a 2 cm nodule posterior to the kidney, which was biopsied, and two enlarged para-aortic nodes (not seen on this image).

Two weeks later, the patient required hospital admission for increasing abdominal pain. Physical exam revealed an elderly gentleman with tachycardia of 102 beats/min. The abdomen was distended and tender throughout with a positive fluid wave, without rebound tenderness or guarding. Biopsy site appeared clean without evidence of a hematoma. Laboratory investigations revealed a leukocytosis. The remaining hematological, biochemical and coagulation profiles were normal.

With new evidence of ascites, an ultrasound-guided paracentesis was performed and extracted 6 L of bloody fluid. Repeat CT imaging revealed concern for urine extravasation. Fluid analysis, however, was not consistent with urinary ascites. Serum-ascites albumin gradient (SAAG) was <1.1 g/dL. Another paracentesis 3 days later extracted 8 L of fluid, again noted to be bloody. Cytology was repeatedly negative for malignant cells.

Urology was consulted and the patient underwent a retrograde pyelogram which verified extravasation at the proximal ureter. A left ureteral stent and subsequently a left nephrostomy tube for urinary diversion.

The patient recovered rapidly and was discharged home, only to be readmitted one day later after a syncopal event. He developed painful abdominal distention from ascites requiring frequent paracenteses that withdrew 23 L of hemorrhagic ascites over 11 days.

Surgical Oncology was consulted for a malignancy workup. Tumor markers including AFP, CEA and CA 19-9 were negative. A diagnostic laparoscopy revealed purplish discoloration and thickening of omentum with inflammatory reaction on the parietal peritoneum (Fig. 2). The small bowel appeared viable without evidence of enteric leakage. A biopsy of the omentum was performed. Frozen section analysis was interpreted as containing atypical cellular proliferation with extensive areas of necrosis. Twelve liters of bloody peritoneal fluid were aspirated.

Intraoperative image taken during diagnostic laparoscopy that revealed purplish discoloration and thickening of the omentum with inflammatory reaction on the parietal peritoneum.

The patient developed a systemic inflammatory response post-operatively, and required intensive care unit admission. Two days later, the patient returned to the OR for exploratory laparotomy and omentectomy for treatment of continued sepsis and ongoing tissue necrosis. Inspection of the peritoneal cavity revealed a normal liver, gallbladder and pancreas. The small bowel showed evidence of serositis without necrosis. The greater omentum was grossly necrotic with widespread areas of purplish discoloration and was resected. Further inspection of the retroperitoneum revealed a peri-renal mass involving Gerota’s fascia of the lower lobe of the left kidney. The kidney itself appeared normal. Approximately 9 L of bloody ascites fluid were aspirated.

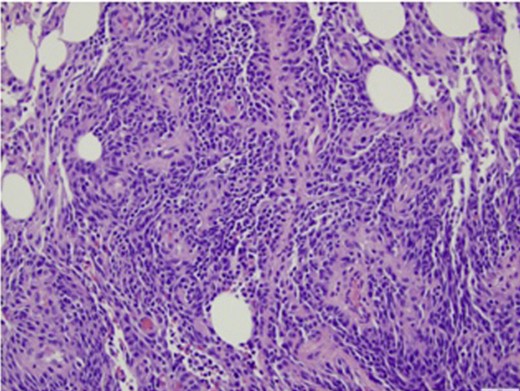

The final histopathology results of the omentum revealed high-grade angiosarcoma (Fig. 3). Due to his multiple co-morbidities, the patient was not a candidate for palliative chemotherapy. His clinical status continued to decline and he died 7 days post-operatively.

Histopathological analysis of formalin-fixed tissue sections of omentum showed diffuse involvement by a spindle cell neoplasm demonstrating both formation of vascular channels and solid areas of growth. Immunohistochemical stains (not shown here) were positive for CD31 and CD34. They were negative for cKit, DOG1, and keratins AE1/3 and cam5.2.

DISCUSSION

Angiosarcomas are a rare sarcoma of endothelial origin and can arise from a variety of sites. These tumors are composed of poorly differentiated endothelial cells, which form highly vascular and hemorrhagic tubular networks [2]. Both retroperitoneal and omental angiosarcomas tend to be aggressive and rapidly fatal if not amenable to early intervention. Surgery and radiation therapy offer the best chance of long-term control [3].

The course of the disease was dramatic and unique, characterized by the reoccurrence of cytology-negative hemorrhagic ascites. Cytological examination of ascites is performed in an effort to diagnose malignant tumors, but the sensitivity of cytology has been estimated to be 60% [4]. The low sensitivity may be due to small numbers of tumor cells in the ascites or the presence of large amounts of leukocytes, mesothelial cells and blood that obscure malignant cells. The associated tumor inflammation results in reactive changes in mesothelial cells that make distinction from carcinoma cells difficult [4]. As evidenced in this scenario, cytological analysis revealed only reactive mesothelial cells with chronic inflammation. Cytology-negative ascites is observed in several malignancies, most notably in ovarian cancer [5]. Due to its rarity, this observation is not well documented in the setting of angiosarcoma.

Ascitic fluid analysis is helpful in distinguishing types of malignancy-related ascites. In a series review, patients with liver metastases had negative cytology but a high SAAG [6]. The patient described in this report had a SAAG<1.1 g/dL, which is more consistently seen with non-malignant causes of ascites. This case again demonstrates a unique pattern of malignant ascites in the setting of angiosarcoma.

Typically, angiosarcomas have pathologic evidence of irregular vascular channels and mitotic figures. On microscopic examination of the omental specimen, there was diffuse spindle cell proliferation with prominent vascular channels in a background of necrosis and tissue hemorrhage. There were frequent mitoses observed. Immunohistochemical stains were positive for CD31 and CD34. The findings were consistent with high-grade angiosarcoma. The biopsy material of the peri-renal mass demonstrated totally necrotic tissue.

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of high-grade angiosarcoma with cytology-negative hemorrhagic ascites and diffuse omental invasion. We conclude that malignancy should be considered in the differential diagnosis in the presence of suspicious cytology-negative hemorrhagic ascites and concomitant retroperitoneal and abdominal findings.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.