-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

David Pisani, Christian Camenzuli, Josephine Psaila, Snežana Božanić, Jean Calleja-Agius, A locally destructive, completely asymptomatic, C1-root schwannoma with base of skull invasion: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2017, Issue 2, February 2017, rjx015, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjx015

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Patients with C1 nerve root schwannomas usually present with signs relating to nerve root compression. However, asymptomatic presentations have never been reported. A healthy, 37-year-old female was referred in view of a slow-growing lump in the left posterosuperior aspect of the neck. The lump was asymptomatic and neurological examination was normal. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a left C1 nerve root tumour, extending around the C1 vertebra and compressing the thecal sac. The tumour had invaded the basiocciput and was impinging on the left cerebellar hemispheric dura. Stereotactic biopsies of the lesion showed a spindle-cell tumour exhibiting an immunoprofile consistent with a schwannoma. The lesion was surgically excised by blunt dissection using a posterior midline approach. The case report adds to the diverse modes of presentation of C1 nerve root schwannomas, in that such lesions must be included in the differential diagnosis of asymptomatic posterior neck lumps.

INTRODUCTION

Schwannomas of the C1 nerve root are rare neoplasms [1]. Cases typically present with signs and symptoms relating either directly to C1 nerve dysfunction or compression of adjacent structures, including the spinal cord and vertebrobasilar arterial system.

We present the case of a young female, who presented in view of a slow-growing posterior neck lump, which was confirmed to be a C1 nerve root schwannoma following imaging and histopathological studies. The case is unique in that, despite the extent of disease, the patient was completely asymptomatic and neurological examination was normal.

CASE REPORT

A 37-year-old Caucasian housewife, with no previous medical history, was referred to the Surgical Outpatient Department in view of a slow-growing lump on the left posterosuperior aspect of the neck. She had first noted the lump 7 years previously. Since it was above the hairline, it was not cosmetically obvious, however, it had been growing slowly over the past years. She was asymptomatic and denied any pain, skin changes or neurological symptoms. Examination revealed the presence of a smooth, hard 5 cm mass in the left posterosuperior aspect of the neck. Neurological and general systemic examinations were unremarkable and blood investigations were normal.

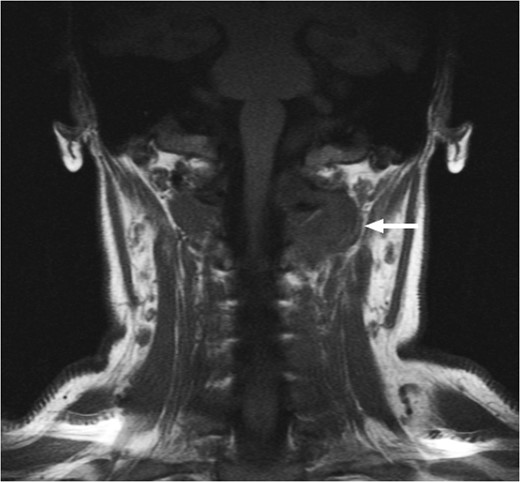

T1-weighted MRI showing the lesion in the posterosuperior aspect of the left neck arising at the level of C1, eroding through the C1 vertebra and displacing the thecal sac.

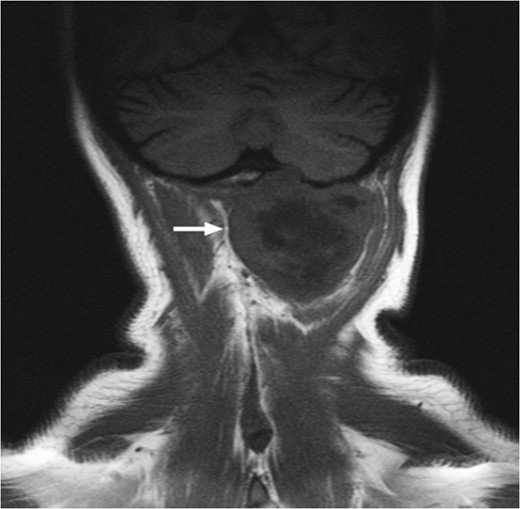

T1-weighted MRI showing the lesion eroding through the left basioccipital skull, impinging the dura overlying the left cerebellum.

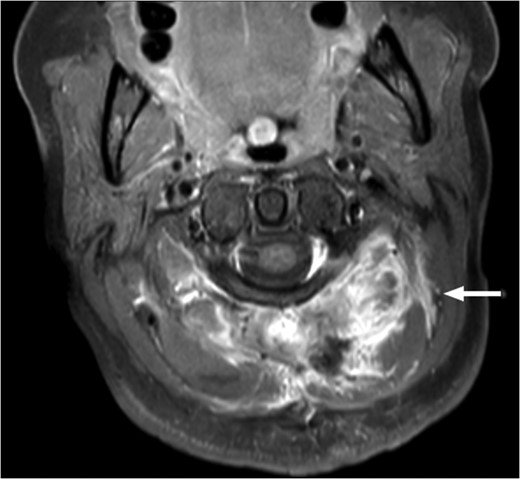

Computed tomographic angiography of the left vertebral artery showing the tumour deriving its vascular supply from the cervical and muscular branches of the artery.

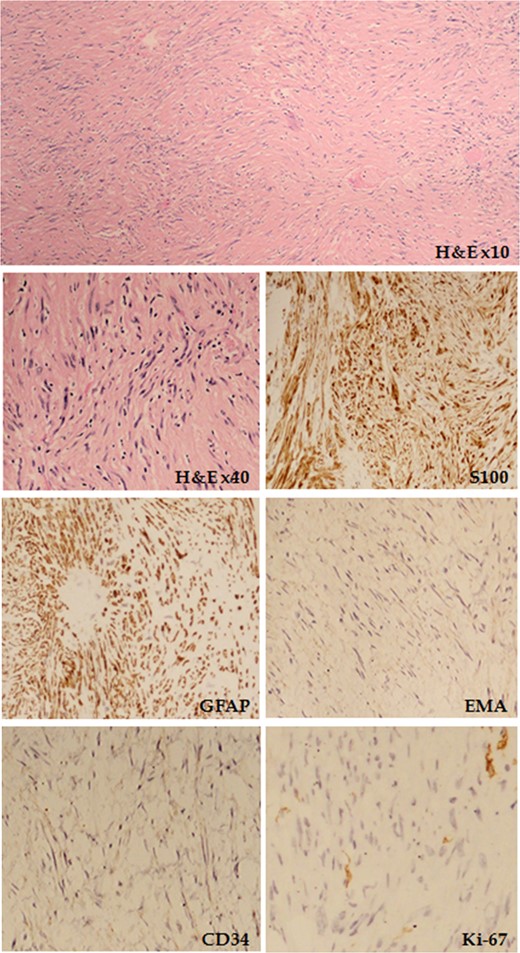

Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining showing spindle-shaped cells organized in whorls and fascicles is shown, together with the tumour immunoprofile for S100, GFAP, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), CD34 and Ki-67.

The patient agreed to undergo extirpation of the schwannoma following extensive consultation. The procedure was performed under general anaesthesia, with the patient prone, her head fixed in a Mayfield frame and her shoulders strapped caudally. She was given 300 mg of clindamycin preoperatively and, following serial skin disinfection, a midline incision was made extending from the external occipital protruberance to the level of the third cervical vertebra. Monopolar dissection was carried out down to the occiput and spinous vertebral processes, hence exposing the tumour, which was subsequently enucleated by blunt dissection. Tumour remnants were excised using microscopic dissection. The point of abutment of the tumour with the intracranial subcerebellar dura, which corresponded to a small opening in the tentorial membrane, was diathermied. A ‘Redivac®’ drain was applied, the musculofascial plane was closed with ‘Vicryl® 1/0’, the dermis was closed with ‘Vicryl® 2/0’ and the skin was apposed using ‘Prolene® 3/0’.

T1-weighted MRI scan showing the presence of scar tissue at the previous tumour site 6 months post-operatively. There is no evidence of residual tumour.

DISCUSSION

Schwannomas are benign neoplasms that originate from Schwann cells surrounding peripheral nerves. They form part of a larger category of tumours referred to as peripheral nerve sheath tumours [1]. Schwannomas are usually solitary lesions, and can arise from any peripheral nerve, often originating from the sensory nerve roots, with motor and autonomic nerves being less frequently involved. Rarely, schwannomas can arise from brain, spinal cord or gastrointestinal parenchyma [2]. They are most commonly observed in patients between the ages of 20 and 50 years, in a roughly equal gender distribution [1, 2].

The pathogenesis behind schwannomas is incompletely understood and most cases tend to be sporadic in nature. However, several genetic syndromes are associated with the formation of schwannomas. Neurofibromatosis Type 2, which is caused by point mutations in the NF2 gene, is associated with the formation of unilateral or bilateral neuromas of the vestibular nerve, with 70% of patients also suffering from numerous peripheral schwannomas [2]. Conversely, schwannomatosis, which is associated with mutations in the SMARCB1 gene, results in the formation of numerous peripheral, often painful, schwannomas, affecting the neck, trunk and extremities [3]. The Carney complex, a condition caused by an autosomal dominant mutation in the PRKAR1A gene, is associated with the formation of atrial myxomas, lentigines, blue nevi and myxoid schwannomas that often affect the upper gastrointestinal tract and sympathetic chains [2].

Schwannomas arising from the C1 nerve root are extremely rare. This is because the C1 nerve is unique, in that, unlike the other spinal nerves, it lacks a well-defined sensory root. However, microscopic clusters of sensory neurons in the C1 nerve root have been illustrated in roughly two-thirds of the population, with half of these cases having a primary dorsal root and the rest deriving the sensory component from the spinal accessory nerve [4]. Multiple case reports for C1 schwannomas exist, as illustrated in Table 1, however, this case is unique in that it is the first C1 cervical schwannoma to be completely asymptomatic.

A synopsis of C1 nerve root schwannomas and their respective clinical presentations.

| Authors . | Year . | Age (years) . | Gender . | Presentation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gopalakrishnan et al. [5] | 2011 | 40 | Male | Giant cystic craniovertebral schwannoma with raised intracranial pressure and masquerading as a fourth ventricle mass |

| Yousefzadeh et al.[6] | 2009 | 60 | Female | C1 ventral root schwannoma presenting with occipitocervical pain, spastic quadriparesis and dissociative sensory loss |

| Kalavakonda et al. [7] | 2000 | 52 | Male | Left-sided C1 schwannoma with left vertebral artery compression, causing vertigo on turning the head to the right and extending the neck |

| Han Kim et al. [8] | 2005 | 60 | Female | C1 schwannoma eroding the C1 articular facet and transverse process, causing neck pain but no neurological symptoms |

| Helmes et al. [9] | 2012 | 29 | Female | C1 schwannoma presenting as a mass in the craniocervical region with numbness and weakness of the left arm and leg |

| Authors . | Year . | Age (years) . | Gender . | Presentation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gopalakrishnan et al. [5] | 2011 | 40 | Male | Giant cystic craniovertebral schwannoma with raised intracranial pressure and masquerading as a fourth ventricle mass |

| Yousefzadeh et al.[6] | 2009 | 60 | Female | C1 ventral root schwannoma presenting with occipitocervical pain, spastic quadriparesis and dissociative sensory loss |

| Kalavakonda et al. [7] | 2000 | 52 | Male | Left-sided C1 schwannoma with left vertebral artery compression, causing vertigo on turning the head to the right and extending the neck |

| Han Kim et al. [8] | 2005 | 60 | Female | C1 schwannoma eroding the C1 articular facet and transverse process, causing neck pain but no neurological symptoms |

| Helmes et al. [9] | 2012 | 29 | Female | C1 schwannoma presenting as a mass in the craniocervical region with numbness and weakness of the left arm and leg |

A synopsis of C1 nerve root schwannomas and their respective clinical presentations.

| Authors . | Year . | Age (years) . | Gender . | Presentation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gopalakrishnan et al. [5] | 2011 | 40 | Male | Giant cystic craniovertebral schwannoma with raised intracranial pressure and masquerading as a fourth ventricle mass |

| Yousefzadeh et al.[6] | 2009 | 60 | Female | C1 ventral root schwannoma presenting with occipitocervical pain, spastic quadriparesis and dissociative sensory loss |

| Kalavakonda et al. [7] | 2000 | 52 | Male | Left-sided C1 schwannoma with left vertebral artery compression, causing vertigo on turning the head to the right and extending the neck |

| Han Kim et al. [8] | 2005 | 60 | Female | C1 schwannoma eroding the C1 articular facet and transverse process, causing neck pain but no neurological symptoms |

| Helmes et al. [9] | 2012 | 29 | Female | C1 schwannoma presenting as a mass in the craniocervical region with numbness and weakness of the left arm and leg |

| Authors . | Year . | Age (years) . | Gender . | Presentation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gopalakrishnan et al. [5] | 2011 | 40 | Male | Giant cystic craniovertebral schwannoma with raised intracranial pressure and masquerading as a fourth ventricle mass |

| Yousefzadeh et al.[6] | 2009 | 60 | Female | C1 ventral root schwannoma presenting with occipitocervical pain, spastic quadriparesis and dissociative sensory loss |

| Kalavakonda et al. [7] | 2000 | 52 | Male | Left-sided C1 schwannoma with left vertebral artery compression, causing vertigo on turning the head to the right and extending the neck |

| Han Kim et al. [8] | 2005 | 60 | Female | C1 schwannoma eroding the C1 articular facet and transverse process, causing neck pain but no neurological symptoms |

| Helmes et al. [9] | 2012 | 29 | Female | C1 schwannoma presenting as a mass in the craniocervical region with numbness and weakness of the left arm and leg |

Traditionally, these lesions have been described on the basis of anatomy, with intradural lesions arising from the intrathecal portion of the C1 nerve root, and extradural lesions arising anywhere along the C1 nerve following passage through the theca. Dumbbell lesions have both an intradural and extraudral component. The management of these tumours tends to be complex, varied and case-specific. Overall, a posterior approach is usually favoured for C1 schwannoma resection, owing to the relative low vascularity of the nuchal and paranuchal area, the absence of vital anatomical structures in the posterior dissection plane, all the while achieving optimal exposure of the tumour. A far lateral approach is only opted for in rare cases of tumours projecting anteriorly [10].

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.