-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Alexandria Papadelis, Collin J. Brooks, Renato G. Albaran, Gastric glomus tumor, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2016, Issue 11, November 2016, rjw183, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjw183

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

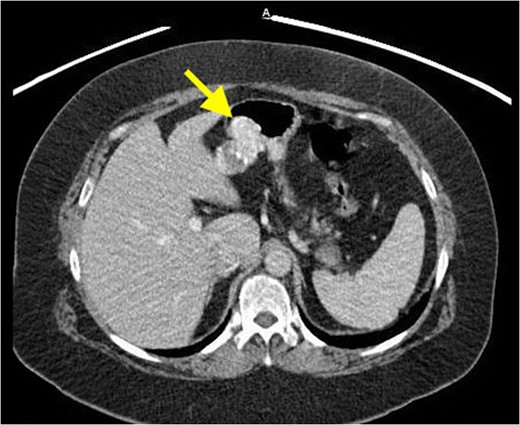

Gastric glomus tumors are rare, mesenchymal neoplasms, generally described as benign and account for nearly 1% of all gastrointestinal soft tissue tumors. The most common gastrointestinal site of involvement is the stomach, particularly the antrum. Gastric glomus tumors are submucosal tumors that lack specific clinical and endoscopic characteristics, and are often mistaken for the more common gastrointestinal stromal tumors. A 62-year-old Caucasian female presented with shortness of breath and a persistent cough. Clinical workup revealed a mass in the upper abdomen. After endoscopic ultrasound and fine needle aspiration raised concerns for cancer, the patient elected to proceed with exploratory laparotomy. A local resection was performed at the time of surgery. Pathologic and immunohistochemical findings following surgical resection were consistent with a gastric glomus tumor. Consideration of gastric glomus tumors in the differential diagnosis may optimize the chance for a more accurate preoperative diagnosis and targeted surgical intervention.

INTRODUCTION

Glomus tumors (GTs) are rare, benign mesenchymal neoplasms arising from a neuromyoarterial glomus body, a dermal arteriovenous shunt responsible for skin thermoregulation [1]. These tumors represent approximately 2% of all soft tissue tumors and are commonly found on extremities. GTs rarely involve visceral organs, although tumors in the tympanum, mediastinum, trachea, kidney, uterus, vagina and stomach have been described previously [2].

Most GTs occur in the fingers and the stomach has been described as a rare site [3]. The most common gastrointestinal (GI) site of involvement is the stomach, particularly the antrum [4]. Generally, gastric glomus tumors (GGTs) are clinically recognized as benign, but some show a pattern of biological behavior similar to that of malignant lesions [3]. Some cases have been discovered incidentally, but most are symptomatic, presenting with GI bleeding, perforation or abdominal pain [4]. GGTs are submucosal tumors and hence are frequently mistaken for the more common gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) [4]. As GGTs lack specific clinical and endoscopic characteristics, it is difficult to distinguish these tumors from other gastric submucosal neoplasms prior to surgical resection. The diagnosis of GTs is largely dependent upon pathological and immunohistochemical findings [5].

CASE REPORT

Surgical findings revealed a hemorrhagic appearing mass in the epigastrium that was not part of the liver and appeared to arise from the stomach near the lesser curvature. Grossly, the mass was soft and pliable without any typical features of malignancy. Examination of the mucosa via gastrostomy revealed no abnormalities thus local excision of the mass through gastrotomy with 0.5 cm margins was performed.

Microscopically, the mass appeared to be arising in the muscular wall or submucosa of the stomach and was composed of sheets and islands of small, uniform cells with round central nuclei, small amounts of clear cytoplasm and relatively distinct cell borders. The neoplasm contained many blood vessels, some with a staghorn pattern. The neoplasm had areas of cystic degeneration and calcification but no definite tumor necrosis. No mitoses were identified. The neoplasm had invaded through the muscularis propria into the subserosa. Areas were identified where serosa appeared to have been stripped away from the tumor; however, there did not appear to be neoplasm on the actual serosal surface. The maximum size of the tumor was 3.0 cm. Margins of excision appeared negative for involvement.

Multiple immunohistochemical stains were performed with the following results: Actin and calponin positive; pancytokeratin (Lu5), chromogranin, synaptophysin, S100 protein, C117/c-kit and CD34 negative.

In this case, the patient was followed up appropriately post-operatively and recovered uneventfully. She was advised to follow up with an oncologist for preventative testing and monitoring of any future malignancies.

DISCUSSION

GTs of the GI tract are rare, representing around 1% of GI soft tissue tumors [4]. GGTs usually arise in the intramuscular layer and typically occur as a solitary, submucosal nodule that most frequently affects the greater curvature, antrum, and pylorus [2]. The prevalence of GGTs is dominant in females in the fifth or sixth decade, but a wide range of ages has been encountered [6]. The incidence of GGTs is much less common than GISTs with only 1 in 100 diagnoses of GISTs being gastric GT [2]. GIST is the most common submucosal tumor of the stomach and is often included in the differential diagnosis of GGTs. Preoperative diagnosis of GGT is difficult due to the generally deep location of the tumors and due to non-specific and overlapping features with GIST on imaging studies.

On CT, they manifest as well-circumscribed submucosal masses with homogeneous density on unenhanced study and may contain tiny flecks of calcifications [2]. However, it is important to note that imaging techniques fail to differentiate GTs from other stromal or mesenchymal lesions. The above-mentioned imaging features can also be seen with other mesenchymal tumors, such as neuroendocrine tumors, GIST, schwannoma and vascular tumors such as hemangioma and hemangiopericytoma [2]. EUS will show a hypoechoic, well-circumscribed mass located in the submucosa and/or muscularis propria [6, 7]. This is generally only advantageous in identifying the layer of tumor origin. Endoscopic biopsy is typically unhelpful in preoperative diagnosis due to the intramural nature of the tumors [2].

Therefore, pathologic testing and immunohistochemistry is essential in the diagnosis of GGTs. The histologic features and immunohistochemical-staining pattern are characteristic of a GT in the presented case. Tumors less than 5.0 cm tend to behave in a benign fashion; however, biologic behavior cannot be predicted based on histologic appearance, and potential for metastasis cannot be excluded.

Treatment of choice for GGTs is wide local excision, consistent with surgical excision of a GIST tumor. There is no role for extended margins of resection like a gastric adenocarcinoma or a lymph node dissection. Occurrence of GGTs is rare, therefore no standardized guidelines for follow-up care are reported in current literature. As there is a potential for malignancy, long-term follow-up and monitoring is suggested.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- dyspnea

- glomus tumor

- cancer

- chronic cough

- endoscopy

- fine needle biopsy

- differential diagnosis

- preoperative care

- soft tissue neoplasms

- surgical procedures, operative

- european continental ancestry group

- abdomen

- diagnosis

- neoplasms

- stomach

- gastrointestinal stromal tumor

- laparotomy, exploratory

- excision

- endoscopic ultrasound