-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

John Dabis, Hani B. Abdul-Jabar, Hosam Dabis, Implant failure in a proximal femoral fracture treated with dynamic hip screw fixation, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2015, Issue 7, July 2015, rjv064, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjv064

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Dynamic hip screw fixation is a common orthopaedic procedure and to date, still can cause difficulties to the senior trauma surgeon. We present a case where an extra-capsular fracture of the proximal femur was managed with a dynamic hip screw (DHS) fixation. She proceeded to the operating theatre, where the fracture was stabilized with a 75-mm DHS and short-barrelled plate. The implant position was checked with intraoperative screening and the position accepted. Following attempted mobilization at 11 days post-operatively, the patient developed a recurrence of her preoperative pain. X-ray showed that the implant screw had separated from the barrel. Later scrutiny of the intraoperative screening films revealed that the barrel and screw were not engaged at the time of surgery. Intraoperative screening films should be carefully checked to ensure congruity of implant components.

INTRODUCTION

Intertrochanteric neck of femur fractures continues to be a common presenting problem to the orthopaedic trauma surgeon. Anatomical reduction, stable fixation and early rehabilitation are the main goals for the surgery, which can be achieved by intraoperative assessment of the image.

The tip–apex distance has become one of the main methods for predicting the failure of fixation and is a very useful tool when carrying out fixation of the proximal femur in these challenging fractures [1]. When performing the procedure, the barrel of the plate must slide and engage the lag screw, ultimately developing a sliding dynamic hip device. These two implants must engage to set up this construct.

This study emphasizes the importance of intraoperative scrutiny of the implant. The mid-axis alignment of the barrel and screw must be colinear to ensure that they are engaged.

CASE REPORT

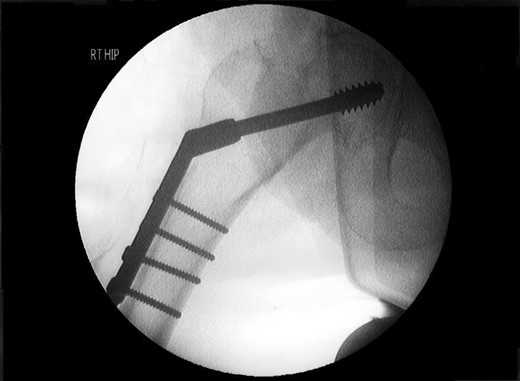

A lady of 88 years old presented with pain in her right hip following a fall at home. Radiographs of the proximal femur revealed an extra-capsular fracture, as shown in Fig. 1. She was taken to the operating theatre within 48 h. In an uncomplicated procedure, the fracture was fixed with a 75-mm, 135°, dynamic hip screw (DHS). A short (25-mm) barrel with four-hole plate was used. Intraoperative screening images are shown in Fig. 2. This position was accepted.

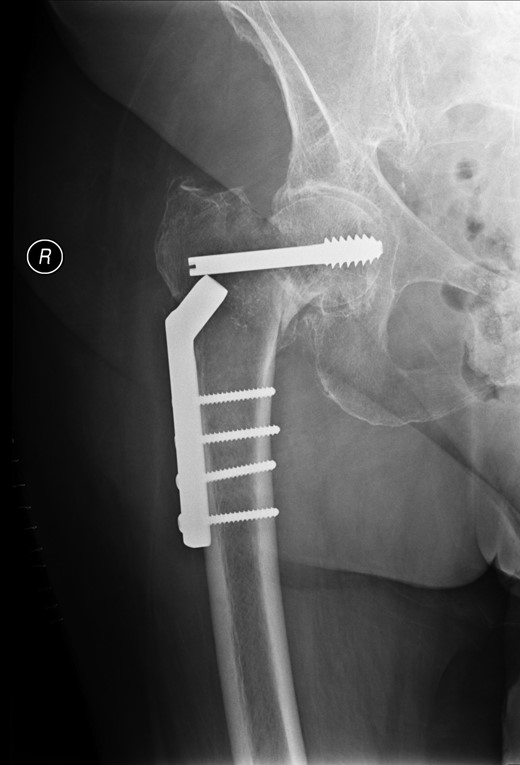

Post-operative nausea delayed immediate attempts at rehabilitation. Although she sat out in a chair, transfers were accomplished with a hoist. At 10 days, post-operatively she was transferred to a peripheral hospital, where rehabilitation commenced with a 2-min period of standing with support. The following morning she complained of greatly increased pain in the operated hip. A radiograph showed that the screw had separated from the barrel, as shown in Fig. 3.

The patient was referred for surgical revision and was treated with a total hip arthroplasty. She made a satisfactory recovery.

DISCUSSION

Review of the intraoperative radiographs (Fig. 2) shows that the barrel and screw are not properly engaged. Although the films may appear satisfactory at first glance, closer consideration reveals that the long axes of the barrel and screw are imperfectly aligned (Fig. 2). Following later experimentation on the bench with identical components, we discover that this is only possible when the length of overlap between barrel and screw is <3 mm. With such minimal overlap, the screw is resting on the lip of the barrel, yet is not fully engaged. In such a position, the screw cannot slide within the barrel. At overlaps greater than this, the screw and barrel cannot be other than coaxial.

Previous correspondents have explained the failure of the screw to slide within the barrel as a ratio of the length contained within the barrel, and the length protruding from it. In order to slide smoothly, without danger of binding, the length of screw protruding should be <4.7 times the length contained within the barrel [2]. This was not achieved here.

We hypothesize that the cause of failure was an intraoperative measurement error, leading to the selection and placement of a 75-mm screw, which was in fact of inadequate length. Thinking, however, that the selection was correct, the surgeon also chose to employ a short 25-mm DHS barrel following recommended practice from the literature [3]. This combination of components was too short to engage properly. Being improperly engaged, they were unable to slide as intended, and upon attempted mobilization by the patient, they immediately uncoupled the one from the other.

Intraoperative screening at the time of placement of the screw may concentrate on visualization of the proximal tip of the implant, to ensure that it occupies a satisfactory position in the femoral head and does not protrude into the hip joint. We stress that equal attention should be paid to the distal end, to ensure that it is correctly aligned with the barrel. Closer scrutiny of the intraoperative screening films for evidence of the appearance described above could have identified this avoidable complication, the resolution of which required major revision surgery.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.