-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sebahattin Celik, Kristina I. Ringe, Cristian E. Boru, Victor Constantinica, Hüseyin Bektas, A case of pancreatic cancer with concomitant median arcuate ligament syndrome treated successfully using an allograft arterial transposition, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2015, Issue 12, December 2015, rjv161, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjv161

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

An association of pancreatic cancer and median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS) is a rare and challenging situation in terms of treatment. A 60-year-old man diagnosed with pancreatic cancer underwent laparotomy. A pancreaticoduodenectomy was planned, but during the resection part of the operation, a celiac artery stenosis was noticed. The patient was diagnosed with MALS causing almost total celiac artery occlusion, with no radiological solution. The patient was re-operated the next day, and an iliac artery allograft was used for aorta-proper hepatic artery reconstruction, concomitant with the total pancreaticoduodenectomy. Preoperative meticulous evaluation of vascular structures of the celiac trunk and its branches is important, especially in pancreatic surgery. A vascular allograft may be a lifesaving alternative when vascular reconstruction is necessary.

INTRODUCTION

Median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS) has been known as an anatomical anomaly since its first anatomical description in 1917 [1]. Today, it is believed that MALS is an anatomic and clinical entity characterized by extrinsic compression on the celiac axis, which leads to postprandial epigastric pain, nausea or vomiting, and weight loss [2]. After clinical suspicion of MALS, lateral conventional angiography of the visceral aorta and its branches is used as the gold standard of diagnosis.

Although there has been a huge number of case reports and case series in the literature, until now there are no guidelines on the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of patients with MALS, one reason being the low incidence of this syndrome. Almost all patients reported in the literature had been diagnosed with MALS before surgery or before other interventions, and afterwards treatment was applied. Here, we want to discuss just a contrary situation, where diagnosis was established incidentally intraoperatively while the patient was undergoing operation for pancreatic cancer.

CASE REPORT

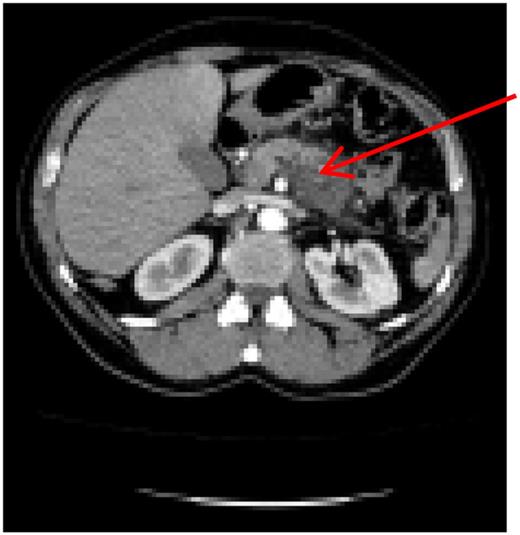

A 60-year-old male, with irrelevant medical history (no chronic disease or treatment), and complaining of recurrent abdominal pain, was referred for abdominal computed tomography (CT). Due to a suspicion of a mass in the pancreatic body (Fig. 1), the patient was referred to our hospital for re-evaluation and treatment. Physical examination was not remarkable, besides epigastric pain during deep palpation. All blood tests were within normal ranges. In re-evaluation of a previous CT, performed in a different hospital, our Radiological Department reported: ‘a malign appearing mass in the pancreatic corpus with extension to the pancreatic neck, with no invasion of the Superior Mesenteric Artery (SMA) and Superior Mesenteric Vein (SMV)’. Laparotomy was performed. Intraoperatively, a mass of ∼6–8 cm was discovered, located from the neck to the corpus of the pancreas. During exploration, the leading surgeon noticed that vascular structures, both the superior anterior pancreaticoduodenal artery (SAPDA) and the inferior anterior pancreaticoduodenal artery (IAPDA), which are collaterals between the gastroduodenal artery (GDA) and the SMA, were enlarged and tortuous. After the Kocher maneuver, all resections (jejunal, postpyloric gastric, common bile duct) were performed. Immediately after the GDA was clamped and cut, an ischemic appearance was seen on the liver and stomach. At this point, it came to mind that there was a total celiac trunk occlusion or possible MALS. To prevent ischemic hepatic injury, immediate re-anastomosis of the cut GDA was performed. After re-anastomosis was completed, a rapid change in the color of the liver and stomach was observed. And after re-anastomosis of the GDA, digital palpation and Doppler ultrasonography revealed that circulation of the common hepatic artery, splenic artery and left gastric artery was restored, and all these vascular circulations were from the SMA via the GDA.

Preoperative computer tomography, mass (arrow) located in corpus of the pancreas.

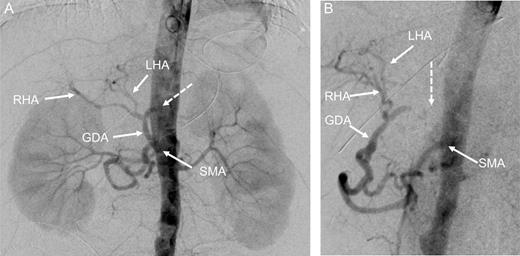

At this point, the patient was recommended for further investigation in the Interventional Radiological Department for both diagnosis confirmation and, most importantly, to provide an opportunity for stenting the celiac trunk. In order to accomplish this, gastro-duodenostomy, choledoco-choledocostomy (anastomosis between the resected common bile duct) and jejuno-jejunostomy re-anastomosis were performed, and a temporary abdominal closure was done. The patient was taken to the Radiological Department. CT and angiography (Figs 2 and 3) showed that there was a narrowing part of the celiac trunk, and distal to this part, there was an occlusion (high degree of stenosis) of the celiac artery. In addition, retrograde filling of the GDA could be appreciated through the patent SMA (Fig. 3). A stent was considered impossible due to the high degree of stenosis that was a nearly total occlusion of the celiac trunk.

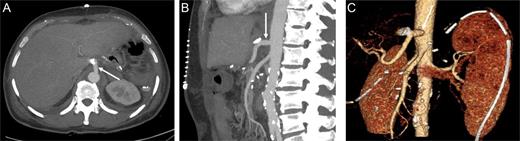

Contrast-enhanced CT in the arterial phase: axial (A) and sagittal (B) maximum intensity projections (MIP), and coronal oblique 3D volume-rendered (VR) images (C) demonstrating proximal celiac artery narrowing (arrow) due to compression by the median arcuate ligament. Downstream, an additional high-degree stenosis of the celiac trunk can be appreciated (dashed arrow).

Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) with pigtail catheter placed in the abdominal aorta: coronal (A) and 70° left anterior oblique (LAO) projections (B) demonstrating complete occlusion of the celiac trunk (dashed arrow). In addition, retrograde filling of the GDA can be appreciated through the patent SMA. RHA, right hepatic artery; LHA, left artery.

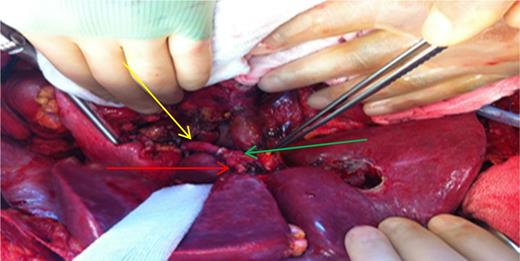

The second operation was performed 20 h later. The patient was intubated during this 20 h. During the second look, total pancreaticoduodenectomy, splenectomy and near total gastrectomy were performed. As our center is a high-volume transplantation center, most of the time we take account of vascular grafts. In this case, we performed an aorta-proper hepatic artery anastomosis by placing an iliac artery allograft (Fig. 4). The anastomosis between the aorto-allograft was performed as lateral to end, and the anastomosis between allograft and proper hepatic artery was end to end, using a 6/0 polypropylene suture (Fig. 4).

Intraoperative demonstration of reconstruction. Yellow arrow: reconstructed graft. Red arrow: left hepatic artery. Green arrow: right hepatic artery. Pensete shows Choledoch.

The patient's post-operative hospital stay was uneventful, and control CT demonstrated patent reconstruction (Fig. 5).

Contrast-enhanced CT in the arterial phase after celiac trunk reconstruction: axial (A) and sagittal (B) MIP, and coronal oblique 3D VR images (C) demonstrating patent reconstruction with an iliac graft (arrow).

DISCUSSION

As we tried to describe in this case, all preoperative investigations can be insufficient to reveal all hidden disease. Especially when one is focused on a serious pancreatic cancer, it is easy to miss a rare vascular anatomic anomaly like MALS. Actually, there are many case reports and case series in the literature [2–4]. Accordingly, the prevalence of MALS in periampullary region cancer is ∼2–4.2% [4–7]. Most of these reported cases had been diagnosed preoperatively, except the cases reported by Kurosaki et al. [5], Nakano et al. [6] and Halazun et al. [7], and except the series reported by Farma et al., where diagnosis was established intraoperatively.

In order to restore upper gastrointestinal organ blood flow in the case of MALS, different approaches have been reported, from endovascular stenting to arterial reconstructions [4, 7, 8]. We appreciate that our case is the first one in which an arterial allograft was used for this purpose.

We did not think to preserve collaterals and the GDA because of tumor invasion and, in case of preservation, surgery should have been oncologically insufficient. Also, we could not use the splenic artery, which had been resected with the total pancreatectomy, because of the same oncological issues. After confirmation of celiac artery occlusion and the impossibility of stenting by the Interventional Radiological Department, we had to make an arterial reconstruction after <24 h.

Consequently, in patients who are scheduled for pancreaticoduodenectomy, preoperative radiological evaluation must be done, remembering the possibility of MALS. The surgeon should always check arterial territories of the celiac trunk before cutting the GDA. Otherwise, the surgeon should be prepared for very unpleasant consequences.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

ETHICAL STATEMENT

Written informed consent was obtained from patient.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank to Turkey Cancer Foundation for scholarship that given author S.C. And we thank to Juergen Klempnauer, M.D. Director, Clinic for Visceral and Transplant Surgery for accept us (S.C., C.E.B., V.C.) as visiting surgeons to their clinic.