-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kalpa G. Perera, Ed Wong, Terry Devine, Stent graft infection secondary to appendicitis: an unusual complication of endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2014, Issue 10, October 2014, rju108, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rju108

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We present a case of a 73-year-old gentleman with an aortic endograft infection post endovascular abdominal aneurysm repair (EVAR), from whence erosion has come in from an acutely inflamed appendix. To our best understanding, there is no similar case published in the literature. Intra-operatively, there was obvious inflammation and oedema over the retroperitoneal tissue, with frank pus and thrombotic material projecting from the aorta. The tip of an obviously inflamed appendix had stuck to and eroded through the aortic sac, seeding the infection. The endograft was explanted and the aneurysm sac oversewn. Lower limb circulation was preserved with a right axillo-femoral Dacron bypass graft. This case highlights a rare complication following EVAR, and for one to consider unusual sources of graft infection.

INTRODUCTION

Endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (EVAR) is an entrenched alternative to open surgical repair (OSR) of abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA). Historically, the incidence of prosthetic aortic graft infections is described as 0.6–3% [1]. Yet, rarely have graft infections post EVAR been reported and there is insufficient published data to establish their true incidence. We present a case of appendicitis-related stent graft infection post EVAR. To our knowledge, there is no similar case published in the literature.

CASE REPORT

A 73-year-old gentleman was admitted with an infected infrarenal AAA and endograft secondary to appendicitis where the tip of the appendix had eroded into the aneurysm sac.

He was 16 months post percutaneous aorto-left-uni-iliac endograft for the treatment of an infrarenal AAA and a thrombosed right common iliac artery (CIA) aneurysm. After the initial procedure, the gentleman underwent a left to right femoro-femoral Dacron crossover graft to preserve right leg circulation. Routine follow-up of these procedures revealed no complications.

Past medical history includes hypertension, type II diabetes mellitus, an aortic valve replacement, radical prostatectomy and removal of bladder polyps. He also had previous anticoagulation therapy for prior left and right superficial femoral artery emboli.

The patient was admitted to emergency department complaining of 1-week fever with worsening back pain. On examination, the gentleman was tachycardic and febrile yet without abdominal tenderness. His significantly raised inflammatory markers coupled with Proteus mirabilis isolated in blood cultures suggested a septic process.

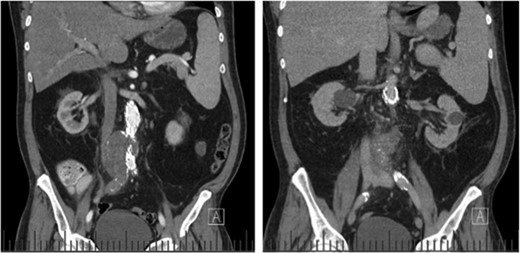

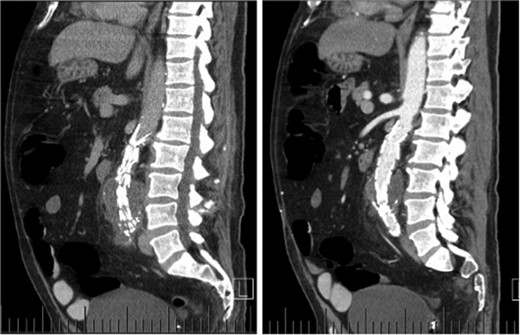

Computed tomography (CT) angiography revealed increased aortic size compared with a scan 1-month prior (5.4 cm compared with 5.0 cm) with diffuse peri-aortic inflammation. The findings implied an infected endograft (Figs 1 and 2).

Coronal CT images indicating enlarged aneurysm sac (left) and para-aortic fat stranding (right) representing periaortitis.

Sagittal CT images indicating enlarged aneurysm sac (left) and para-aortic fat stranding (right) representing periaortitis.

To preserve lower limb circulation, the gentleman underwent a right axillo-femoral Dacron bypass graft. Both right axillary and groin wounds were closed temporarily with staples, to be reopened and closed formally once the abdominal component of the procedure was complete.

Upon laparotomy there was widespread inflammation and oedema, with the appendix strongly adherent to the distal aneurysm sac. The retroperitoneal tissue over the aneurysm was divided, projecting grey pus and old thrombotic material. The tip of the appendix, which had stuck to and eroded through the aneurysm sac, was visible highlighting it as the cause of the infection.

With the supra-coeliac aorta and left CIA cross-clamped, the endograft was divided and explanted. Debridement and lavage of the aneurysm sac, infected clot and calcified intima was then performed. The remaining sac was closed over a Jackson Pratt drain.

Following the aortic component of the procedure, the patient underwent an open appendicectomy.

Once the laparotomy wound was closed, all drapes were removed; gloves, gowns and instruments changed, and further prep and drape performed. The axillo-femoral incisions were then closed with sterile equipment. An on table angiogram confirmed appropriate graft flow.

The patient continued on intravenous antibiotics for 6 weeks and a further 12 months of oral co-amoxyclav. He recovered well from the procedure and was transferred to a rehab facility. At current follow-up the gentleman is now 2 years post-explant and bypass with no sign of infection.

DISCUSSION

EVAR offers an immediate and in-hospital benefit compared with OSR, with similar longer term outcomes [2]. Yet, divergent to OSR, EVAR carries the risk of endoleak, thus warranting closer follow-up. Further complications include graft thrombosis, migration and pseudoaneurysm. In contrast to OSR, stent graft infections following EVAR are a known but rarely reported complication. With an incidence of up to 3%, graft infections are well documented in OSR [3]. Although, mostly limited to case reports and series', the true incidence of stent graft infections post EVAR is not agreed upon. The only population-level study of graft infections to date, by Vogel et al. [4] found a reduced 2-year rate of graft infections in EVAR of 0.16 compared with 0.19% in the open surgical group.

With a reported mortality rate of between 11 and 28%, and an amputation rate of up to 11%, graft infection poses severe consequence [4].

Potential sources of infection include nosocomial infection, peri-operative contamination and erosion causing fistulization [5]. Vogel et al. [4] concluded that blood stream septicaemia and surgical site infection were significantly associated with stent graft infection in both open and endovascular procedures.

A review article by Hobbs et al. revealed that at least 68% of cases identified a likely causative organism [6]. In 55% of 65 cases of infection reviewed by Ducasse et al. [7] they found Staphylococcus aureus as the most commonly cultured organism. Other offending organisms include Escherichia Coli, streptococci, Clostridium perfringens and Bacteroides fragilis [6]. Unusually, blood cultures grew Proteus mirabilis in our patient; an organism not usually associated with aortic endograft infection (AGI).

Stent graft infections generally present as one of the three main clinical scenarios; severe systemic sepsis, low-grade sepsis or unusual in the setting of endovascular repair, with evidence of aorto-enteric fistula [6]. With ongoing fevers, tachycardia and back pain, our patient presented with systemic sepsis.

With the diagnosis of stent graft infection, management principles must mirror those of any infected prosthesis. Operative management must ensure adequate debridement of the infected region, closure through normal tissue and appropriate antibiotic coverage. Revascularization can be via extra-anatomic bypass (EAB) or in situ reconstruction with autologous femoral vein, homograft or rifampicin-bonded prosthetic graft. With the risk of stump blowout and variable patency and mortality rates associated with EAB there is an increasing move towards in situ reconstruction options [8–10]. Nonetheless, EAB still offers a versatile and viable alternative as is evident in our case.

Thus, AGI are indeed a potential complication of EVAR and, elucidated by our case, it is worth considering unusual aetiologies.