-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Peter L. Z. Labib, Sohail N. Malik, Choice of imaging modality in the diagnosis of sciatic hernia, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2013, Issue 12, December 2013, rjt102, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjt102

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Sciatic hernias are one of the rarest types of hernia and often pose diagnostic difficulty to clinicians. We report a case of an 80-year-old lady with a sciatic hernia who had a falsely negative computed tomography (CT) but was found to have a colonic hernia on ultrasonography. The authors recommend that for patients in which there is a high degree of clinical suspicion for a sciatic hernia and a negative CT, ultrasonography may be considered as a useful imaging modality to confirm the diagnosis.

INTRODUCTION

Sciatic hernias are one of the rarest types of hernia and often pose diagnostic difficulty to clinicians [1]. Imaging is often required to confirm the diagnosis and usually involves computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). To our knowledge, we report the 115th case of sciatic hernia in the literature who had a falsely negative CT but had the diagnosis confirmed using ultrasonography.

CASE REPORT

An 80-year-old lady was referred to the on-call surgical team by her GP with a 3-week history of a right-sided swelling of the buttock. Although associated with a mild discomfort, there were no urinary or bowel symptoms. Her GP had prescribed a trial of clarithromycin to no effect. She had a past medical history of hypertension, osteoarthritis and pemphigus vulgaris and a past surgical history of a perianal abscess requiring incision and drainage. She was allergic to penicillin and took regular oral betamethasone, xylometazoline nasal spray and topical aqueous cream. She did not consume alcohol, was a non-smoker and lived in warden-controlled accommodation. On examination, her cardiac, respiratory and abdominal examinations were normal. Digital rectal examination revealed a non-tender stool-filled rectum with no palpable masses. On standing, a swelling on the medial aspect of the right buttock became apparent which was easily reducible, had audible bowel sounds and a positive cough impulse. Admission bloods were unremarkable. She was reviewed by the on-call consultant who discharged her with a working diagnosis of possible obturator hernia, with a plan for an outpatient CT of her pelvis and follow-up in clinic.

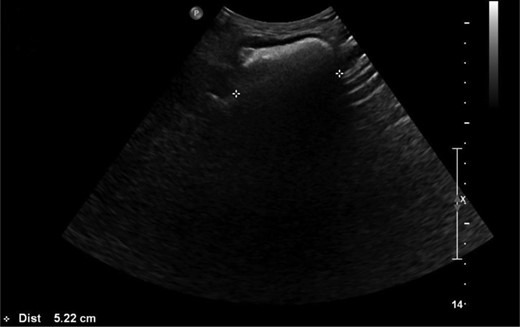

CT scan of the pelvis did not identify a cause for the swelling (Fig. 1). Due to the positional nature of the swelling, a gluteal ultrasound was organized, which revealed a large colonic sciatic hernia (Fig. 2). As the patient had minimal symptoms and was not keen for surgical intervention, a plan for conservative management was agreed and the patient was discharged from clinic.

CT of the patient's pelvis demonstrating a normal right sciatic foramen (arrowed).

Ultrasound image demonstrating the sciatic hernia. (Reported as ‘US Hip Rt: Confirms reducible herniation of colon in the right sciatic region into the buttock.’)

DISCUSSION

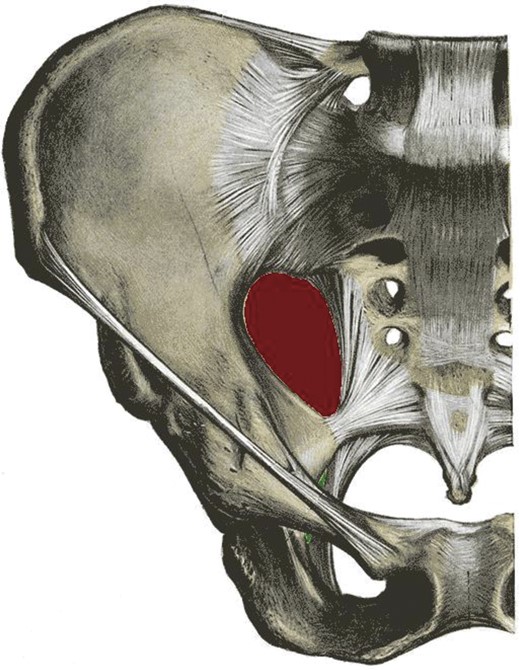

Sciatic hernias are one of the rarest types of hernia and often pose diagnostic difficulty to the clinician [1]. A sciatic hernia is defined as herniation of intraperitoneal contents through either the greater or lesser sciatic foraminae (Fig. 3). The majority of sciatic hernias are found in women (77%) with more than one-third of these being aged 60 or over [1]. The contents are variable and hernias containing ovaries, ureters, bladder, small and large intestine, omentum and dermoid cysts have been reported [1–6]. The wide variability in contents leads in turn to a range of presentations. Cases have been reported with both acute and chronic symptom duration [2–5]. Half of patients report non-specific abdominal or pelvic pain and one third have a mass on clinical examination [1]. Sciatica, intestinal obstruction, urinary sepsis and hydronephrosis have also been described [1–5]. Diagnostic laparoscopy or laparotomy is often required to fully evaluate the sac contents and to repair the defect [2, 3, 5]. In symptomatic patients, surgical repair is indicated due to the high risk of bowel strangulation [1, 3].

Pelvis demonstrating the greater (red) and lesser (green) sciatic foraminae.

Diagnosis by clinical examination alone is possible in only the minority of cases and imaging is frequently used to confirm the suspicion of sciatic hernia. Commonly used imaging modalities are computerized tomography (CT) [2–5] and MRI [3, 4], particularly if the sciatic nerve is thought to be involved. Currently, the most commonly used imaging modality of choice is a CT scan with the patient supine. However, if the hernia is only apparent in a dependent position, this can produce a false-negative result, as in our case. The benefit of ultrasound is that it allows for real-time positional assessment of the region of interest, to reduce the risk of missing this rare but significant hernia.

Due to their rarity, sciatic hernias are often not considered in the differential diagnosis. The authors recommend that all patients presenting with non-specific abdominal or pelvic pain associated with a gluteal swelling should have sciatic hernia considered amongst their differential diagnosis. For patients in which there is a high degree of clinical suspicion for a sciatic hernia and a negative CT, the use of ultrasonography for positional defects may be a useful aid to confirming the suspected diagnosis.