-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jennifer H. Fieber, Jórunn Atladóttir, Daniel G. Solomon, Linda L. Maerz, Vikram Reddy, Kisha Mitchell-Richards, Walter E. Longo, Disseminated enteroinvasive aspergillosis in a critically ill patient without severe immunocompromise, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2013, Issue 11, November 2013, rjt091, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjt091

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Invasive aspergillosis (IA) is a rapidly progressive and often fatal infectious disease described classically in patients who are highly immunocompromised. However, there has been increasing evidence that IA may affect critically ill patients without traditional risk factors. We present a case of a 47-year-old man without conventional risk factors for IA who presented with impending sepsis and proceeded to have a complicated hospital course with a postmortem diagnosis of invasive gastrointestinal aspergillosis of the small bowel.

INTRODUCTION

Aspergillus is a ubiquitous fungus that causes opportunistic infections in the immunocompromised patient population and has a high mortality. Up to 60% of patients with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis will have extrapulmonary dissemination of disease [1]. The gastrointestinal tract is the third most common location for dissemination [2]. The presentation of invasive gastrointestinal aspergillosis (IGA) most commonly includes abdominal pain and gastrointestinal bleeding but may rarely present as an acute abdomen [2, 3]. Diagnosis of IGA infrequently occurs before autopsy [4]. We present a unique case of IGA leading to intestinal infarction and ultimately death in a critically ill patient.

CASE REPORT

A 47-year-old man with a history of hepatitis C, hemophilia A managed on home Factor VIII and, recently, diagnosed ulcerative colitis on prednisone 40 mg for 10 days was transferred to our facility for concern for toxic megacolon and admitted to the medical intensive care unit (MICU). Admission vital signs were temperature 34.4°C, heart rate 96 bpm, blood pressure 107/51, respiratory rate 14 breaths per minute and oxygen saturation 97% on 3 l/min by nasal cannula. On physical examination, the patient was cachectic and his abdomen was distended and diffusely tender but without rebound tenderness or guarding. The rectal examination was positive for gross blood. A non-contrast abdomen and pelvis computed tomography (CT) scan was significant for pancolitis and the patient was started on antibiotics.

Emergency general surgery was consulted, and the patient was transferred to the surgical intensive care unit (SICU). The patient developed hypotension requiring vasopressors and respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. Over the next 2 days, leukocytosis and lactic acidosis normalized, and the patient was weaned off vasopressors and extubated. Clostridium difficile antigen was negative and antibiotics were narrowed.

On hospital day 6, the patient complained of sudden onset sharp abdominal pain and developed peritoneal signs on abdominal examination. Non-contrast abdominal CT scan demonstrated pneumoperitoneum, colitis and ascites. In the context of the patient's co-morbidities, the patient was deemed too high a surgical risk for exploratory laparotomy. The patient was taken to the operating room for a loop ileostomy rescue procedure. Intraoperatively, the small bowel appeared normal, and ascites appeared clear. The patient was extubated postoperatively and initially improved.

On postoperative day 3, he developed supraventricular tachycardia, respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation, hypotension requiring vasopressors and large-volume serosanguinous ascites drainage from the intra-abdominal drain. Concurrently, intraoperative ascites cultures grew Candida, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and E. coli and appropriate antibiotic therapy was initiated. Sputum cultures grew 1+ Aspergillus fumigatus. A repeat endotracheal (ET) aspirate culture was negative for fungus, and a non-contrast chest CT scan demonstrated no evidence of a fungal pneumonia. For the next week, the patient remained intubated but was successfully weaned off vasopressors, and his abdominal examination improved.

On postoperative day 14, peritoneal signs and acute hypotension requiring vasopressors recurred. The patient developed black ileostomy output, bleeding from the intra-abdominal drain and bright red blood per rectum. The patient underwent an emergent exploratory laparotomy. Intraoperatively, the small bowel was necrotic from the distal jejunum to the distal ileum. Seventy-three centimeters of small bowel were resected, and a primary anastomosis was performed.

Postoperatively, the patient had profuse, uncontrollable intra-abdominal bleeding and remained hemodynamically unstable. Despite massive transfusion and aggressive attempts to correct coagulopathy, the patient continued to deteriorate. Goals of care were changed to comfort measures, and the patient died the next morning. Concomitantly, a third ET aspirate culture was positive for 2+ A. fumigatus. The family refused autopsy.

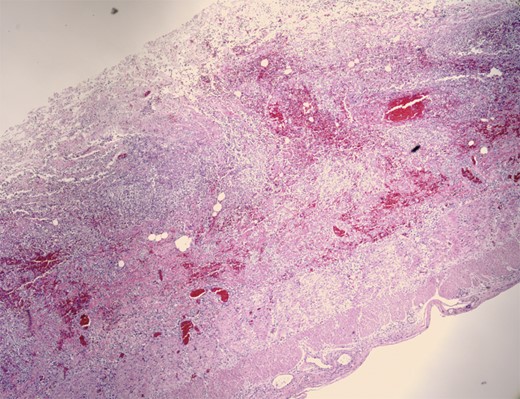

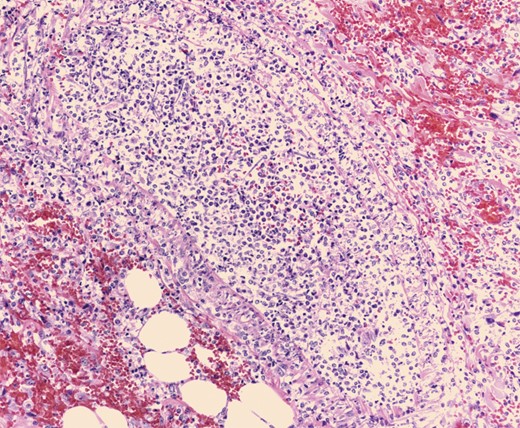

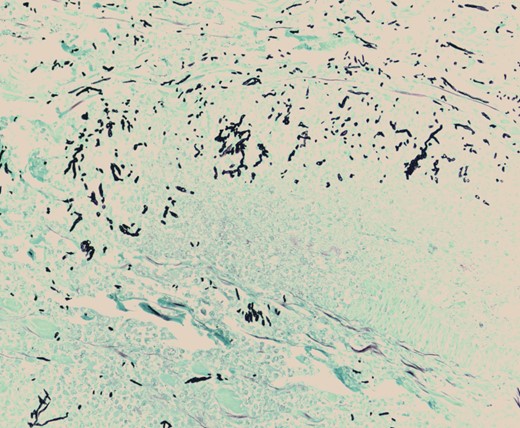

Pathologic evaluation of the resected bowel revealed hemorrhagic, gangrenous bowel (Fig. 1) and granular friable, ulcerated mucosa (Fig. 2). Microscopically, there were areas of transmural bowel necrosis (Fig. 3) and fungi within the bowel wall, artery wall and lumen (Fig. 4). Gomori Methenamine Silver stain was characteristic of Aspergillus species (Fig. 5).

Hemorrhagic bowel with dark purple–black areas of gangrene and foci of serosal fibrinopurulent exudate.

Admixed blood clot and fecal material, focally adherent to the granular, friable mucosa with associated exudate and edema.

Mononuclear cells associated with scattered neutrophils and prominent fungal hyphae in subserosal arteries and invading vessel walls.

Gomori Methenamine Silver stain highlighting fungal forms, some dichotomous, with frequent septation, characteristic of Aspergillus species.

DISCUSSION

We present a case of fatal IGA in a critically ill patient with newly diagnosed ulcerative colitis managed with low-dose steroids, hemophilia A and hepatitis C. Traditional risk factors for IA include neutropenia, stem cell transplants, organ transplants and advanced AIDS [4]. Steroid courses longer than 3 weeks and prednisone dosage ≥1.25 mg/kg/day also increase risk of IA [5, 6]. Critical illness is increasingly being considered as possible risk factor of IA in non-neutropenic patients [7].

The diagnosis of IA is difficult in classically high-risk patients, as symptoms are ill defined, radiologic studies are only suggestive of the diagnosis and cultures are not sensitive [8]. Invasive aspergillosis provides a further diagnostic challenge in critically ill patients, as symptoms can often be explained through other aspects of the patient's presentation [6]. Diagnostic methods for IA have only been thoroughly studied in traditional immunocompromised patients [8]. Differentiating colonization from invasive infection in positive ET culture aspirates continues to be difficult, and the value of newer antigen-based testing in non-neutropenic patients has been questioned [4, 6, 9]. Invasive testing for histopathological diagnosis is often contraindicated in critically ill patients.

The diagnosis of IGA was extremely challenging in our patient because of his complex clinical presentation and lack of classic risk factors. He presented with gastrointestinal bleeding, colitis and sepsis in the context of ulcerative colitis, corticosteroids and coagulopathy. His gastrointestinal symptoms were nonspecific and readily explained by his comorbidities. Our patient did have comorbidities known to impact immune function, including critical illness, short course corticosteroid use, malnutrition and liver dysfunction but was not considered to be at high risk of developing IA.

When the initial sputum culture grew A. fumigatus, the possibility of IA was investigated through imaging that was not consistent with fungal infection and a negative repeat ET aspirate culture. The initial sputum culture was thought to be a contaminant or colonization. We believe that our patient had a primary subclinical lung infection with secondary angioinvasion of the small bowel leading to this severe complication. In conclusion, the diagnosis of IGA is difficult, especially in nontraditional hosts, but should be considered as part of the differential diagnosis in critically ill patients with nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms.