-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Hendrik Jansen, Sönke P. Frey, Stefanie Doht, Rainer H. Meffert, Simultaneous posterior fracture dislocation of the shoulder following epileptic convulsion, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2012, Issue 11, November 2012, rjs017, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjs017

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Shoulder dislocations with fractures are a possible complication of an epileptic seizure and are often missed on the first sight. The incidence of sustaining an avascular humeral head necrosis (AVN) is high, and primary prosthetic replacement is the choice of treatment. In this paper, we describe such a rare case: a 48-year-old male patient sustained simultaneous bilateral posterior shoulder dislocation with fractures of both humeral heads following the first episode of an epileptic convulsion. On the left side, open reduction and internal fixation were performed with angle stable plate osteosynthesis. In the same operation, a hemi-prosthesis was implanted on the right side. One and a half years postoperatively, function on the right side is unsatisfying and AVN is seen on the left side and secondary prosthetic replacement had to be performed. In case of a shoulder dislocation with a complex fracture after an epileptic seizure, prosthetic replacement is the choice of treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Bilateral fracture dislocation of the shoulder is a rare event [1–3]. In the presented case, the epileptic seizure of these patients was the causation for the injury. In literature, there are less than 40 cases of this type of injury described. High forces are needed to sustain this uncommon injury. This has been described by Brackstone et al. as the ‘triple E syndrome’: epilepsy, electrocution and extreme trauma [1]. For correct diagnosis, proper imaging is mandatory [4, 5] as this injury is often not or misdiagnosed in up to 80%. The treatment in most cases was open reduction with either osteosynthesis or prosthetic replacement of the humeral head.

CASE REPORT

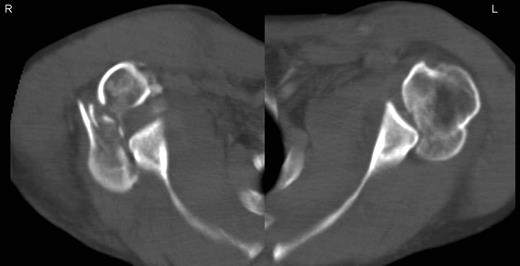

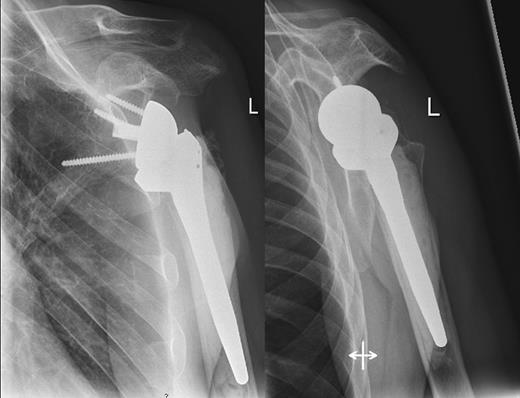

A 48-year-old patient was referred to a level I trauma center after the first incidence of an epileptic convulsion. The patient was alert and oriented with retrograde amnesia from the time of convulsion. Peripheral neurology was normal. The X-rays showed bilateral posterior shoulder dislocation with fractures of both humeral heads (Fig. 1). A CT of the head and both shoulders was performed to exclude intracerebral pathology and to achieve better demonstration of the shoulder fractures (Fig. 2). According to the AO fracture classification, he had a 11-C3.1 fracture on the left side and a 11-C3.3 fracture on the right side. The right side fracture was treated with a cementless hemiarthroplasty (OrTra®, Zimmer, Germany), while an open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) with an angular stable plate (Philos®, Synthes, Germany) was performed on the left. Despite the high incidence for humeral head necrosis after ORIF in this fracture type, this option was chosen based on the young age of the patient. Postoperative X-rays and CT showed adequate positions of the implants (Fig. 3). The shoulders were immobilized in Gilchrist bandages followed by passive mobilization for the first 6 weeks by physiotherapy with a limitation for abduction and anteversion to 90°. There were no complications intraoperatively or in the first postoperative time. Patient was discharged after 8 days. Antiepileptic therapy was initiated with 5 mg clobazam and subsequent increasing doses over the following weeks. There were no more signs of epilepsy in the follow-up. A CT 4 months after operation showed dislocation of a fragment on the left side which was subsequently resected. At the 1-year postoperative review, the patient showed impingement of the left shoulder with abduction limited to 50° by both the plate and an osteophyte. Radiological assessment revealed signs of necrosis of the head. The plate was removed and the osteophyte resected. Eighteen months after injury, the left shoulder showed progressive avascular osetonecrosis of the head (Fig. 4) and after plate removal an inversed prosthetic replacement had to be performed (Fig. 5). At the last follow-up 3 years after injury, the patient was free of pain with a bilateral range of motion of 90° abduction and elevation.

Postoperative X-rays after hemiprothetic replacement on the right and angle stable plate osteosynthesis on the left side.

Avascular head necrosis over the following one and a half years on the left side with ongoing necrosis after plate removal.

DISCUSSION

Avascular necrosis of the humeral head is a common complication following displaced humeral head fractures [6]. Conservatively treated fractures show an incidence of avascular necrosis of between 3–14 and 13–34% in the cases of three fragments and four fragments, respectively [7]. There is a much higher rate in dislocated fractures. Povacz et al. [8] described a rate of necrosis in 21.7% in four-fragment fractures and as much as 50% in the case of dislocated four-fragment fractures. Plate osteosynthesis of these fractures can also lead to avascular necrosis with rates up to 35% in complex articular fractures as reported by Gerber et al. [9]. When considering prosthetic shoulder replacement, elderly patients seem to receive the most positive outcomes when compared with younger patients. In young patients, the results after prosthetic replacements are unsatisfactory, with a mean Constant–Murley score of 62.65 [6]. Despite this, Habermeyer describes better results in primary replacement compared with secondary replacement after failed osteosynthesis [10]. This complicates the decision for the surgeon in cases of younger patients with fractures.

In our case, both operative procedures were performed. Owing to the young age of the patient (48 years), we tried to avoid acute prosthetic replacement of both sides. As the left side was less comminuted (AO 3.1 fracture type vs. AO 3.3 contralateral), we gave osteosynthesis a chance, being aware of the high incidence of avascular humeral head necrosis (AVN) in the literature with up to 50% as mentioned above. Unfortunately, AVN occurred over the time. The function of the right side after hemiprosthesis and on the left side after switching to an inversed prosthesis is free of pain with moderate range of motion.