-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

P Ariyaratnam, J Cooke, D Dasgupta, K Wedgwood, Rare benign pathologies mimicking malignancy: A cautionary tale for Whipple’s resections, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2011, Issue 2, February 2011, Page 7, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/2011.2.7

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Benign pathologies demonstrated after a Whipple’s resection (pancreatoduodenectomy) for pancreatic and peri-ampullary lesions are relatively uncommon. Here we report two cases where a Whipple’s procedure was undertaken for suspected pancreaticobiliary cancer and where the final histology revealed, in each case, a rare benign lesion. The first case confirmed a cholesterol polyp in the distal common bile duct whilst the second case revealed ampullary intramural ectopic gland hyperplasia. Although pre-operative imaging helps in differentiating some benign lesions from malignant lesions, rare benign pathology may still mimic malignant conditions leading to a Whipple’s resection.

INTRODUCTION

A Whipple’s resection is associated with a high morbidity and a significant mortality rate (10). The decision to undertake such an operation should, therefore, only materialise after careful consideration of the pre-operative laboratory and radiology data (4). The ability to accurately determine, microscopically, if a pancreatic or peri-ampullary lesion is benign or malignant, pre-operatively, is hindered by the relative inaccessibility of the head of the pancreas and its associated structures to biopsy (8). The literature reports that around 7% of the histology obtained post-Whipple’s resection are benign (5). Here we present two cases initially deemed at the Hepato-Pancreatico-Biliary (HPB) multi-disciplinary team (MDT) meeting to require a Whipple’s resection, which upon post-operative histological analyses were confirmed

CASE REPORT

Case 1

SC was a 46 yr old gentleman who was referred from his district hospital with a six month history of upper abdominal pain and weight loss. His past medical history included a prolapsed lumbar disc and he was not on any regular medications. A family history revealed that his grandfather had gastric cancer. He was a non-smoker and had a moderate alcohol intake. A Computer Tomography (CT) scan of his abdomen and pelvis revealed no significant abnormalities except for changes suspicious of duodenal diverticular disease. Prior to his consultation he had endoscopies of both his upper and lower gastro-intestinal tracts which were reported as revealing no abnormalities. An Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangio-Pancreatogram (ERCP) was precluded due to the difficulty of the duodenal diverticulum obscuring the ampulla of Vater. A subsequent Endoscopic Ultrasound Scan (EUS) revealed an 8mm soft tissue lesion in the distal common bile duct (CBD) causing dilatation of the pancreatic duct (Figure 1). Elastography showed this to be a firm mass. FNA sample were subsequently taken from the mass which revealed no malignant cells. The HPB MDT meeting felt that although the lesion could be benign, a malignant process could not be excluded thus a Whipple’s procedure was advised.

His admission Full Blood Count, Biochemical profile, Liver Function Tests and Clotting were all within normal limits.

Laparotomy revealed no evidence of bilary dilatation and no obvious malignant mass identified although some thickening of the ampulla was seen. A classical Whipple’s procedure was undertaken. SC spent 2 days in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for routine monitoring. On post-operative day 6, SC developed chest sepsis and was commenced on intravenous antibiotics. He subsequently made a full recovery and was discharged home 3 weeks after his operation.

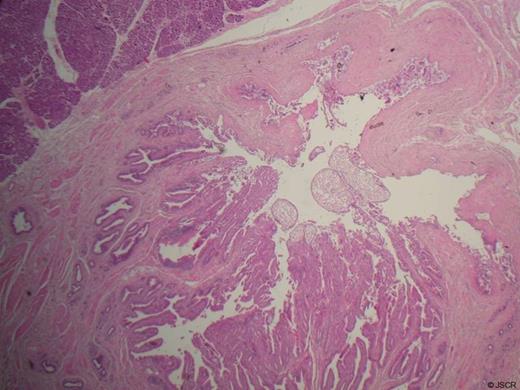

The histology of the operative specimen revealed cholesterol polyps in the distal CBD associated with a juxta-papillary duodenal diverticulum (Figure 2).

Histology at x20 magnification demonstrating cholesterol polyps at the convergence of the distal CBD and main pancreatic duct.

Case 2

PW was a 53 yr old gentleman who was referred from by his General Practioner for recurrent episodes of self-limiting epigastric pain over the course of 3 months which were clinically associated with jaundice. His medical history included a road traffic accident at the age of 7 when he lost his right kidney. He took no regular medication. He was an ex-smoker of 10 pack years and drank one bottle of wine per week. He had a strong family history of ischaemic heart disease and his father died of bowel cancer.

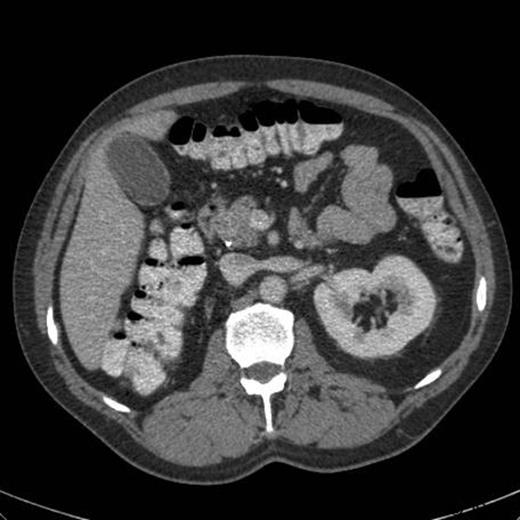

An ultrasound prior to this clinic appointment revealed a dilated Common Bile Duct (CBD) of up to 10mm, a distended thin walled gallbladder, no calculi and a normal pancreatic body. The head of the pancreas was not visualised. Laboratory tests from the GP revealed an elevated bilirubin of 150 umol/L. The CT of his abdomen and pelvis confirmed a dilated CBD and some areas of focal calcification on the head of the pancreas (Figure 3). The EUS demonstrated a thickened distal CBD with a 1.5cm hypoechoic lesion in the pancreatic head (Figure 4). The HPB MDT meeting suspected a malignant lesion and felt that a Whipple’s procedure would offer the best chance of cure.

CT abdomen demonstrating calcification at the head of the pancreas

EUS demonstrating lesion at the pancreatic head with thickening of distal CBD

At laparotomy, the head of the pancreas was felt to be thickened and was adherent to the pylorus of the stomach through fibrotic tissue. A classical Whipple’s operation was undertaken. PW was transferred to ICU post-operatively for routine monitoring for 2 days. His recovery was complicated by sepsis secondary to collection in the gall bladder bed which was drained under radiological guidance. He was discharged one month following his operation.

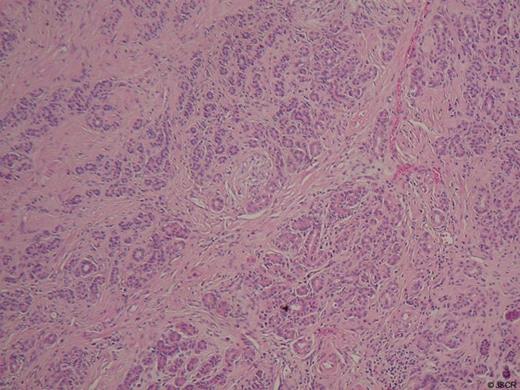

The histology of the resected specimen was reported as showing intramural benign gland hyperplasia within the distal CBD and ampulla (Figure 5).

Histology at x100 magnification demonstrating glandular lobules of duct-like structures within fibrous stroma of the ampulla

DISCUSSION

Cholesterol polyps in the bilary system are most commonly found within the gallbladder (6). They are characterised by mucosal villous hyperplasia with cholesterol-laden epithelial macrophages and are generally asymptomatic (7). In contrast, cholesterol polyps within the CBD are much rarer and can present with obstructive jaundice (9). Such cases have been treated by choledocholithotomy and removal of the polyp. Cholesterol polyps are not proven to have malignant potential (8).

Ectopic glandular tissue at the ampulla of Vater has been previously documented, more commonly of pancreatic origin (3). Many are incidental but occasionally do present with obstructive jaundice (1). Suggested management includes ERCP with a sphicterotomy at the time of biopsy; upon histological confirmation of the diagnosis, limited excision of the ectopic tissue or wide local excision can be undertaken (2).

Both cases illustrate the importance of pre-operative diagnosis as both pathologies can be managed by limited resection rather than a formal Whipple’s procedure. Neither of these patients underwent an ERCP which may have been able to biopsy the lesions in the ampulla and distal CBD. Although an ERCP is a relatively invasive diagnostic procedure with not insignificant risks of pancreatitis, cholangitis and bleeding, it could avoid the need for a higher-risk Whipple’s procedure in rare ampullary or peri-ampullary lesions.