-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

A Reid, A Dettrick, C Oakenful, AL Lambrianides, Primary rectal melanoma, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2011, Issue 11, November 2011, Page 2, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/2011.11.2

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Primary rectal melanoma is rare and only represents up to 4% of anorectal malignancies. The prognosis of such a diagnosis is significantly different to a metastatic melanoma deposit in the anorectal area and therefore differentiation between the two is of the utmost importance with regards to initial treatment and long-term management. Various immunohistochemical markers have been shown to be associated with primary melanoma and strongly aid in diagnosis. Surgical management is still widely disputed and multiple papers have been published comparing wide local excision with abdominoperineal resection. Here a case of primary rectal melanoma is presented with a brief discussion exploring diagnostic techniques, treatment options and prognostic factors.

INTRODUCTION

Anorectal malignancies are commonly adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma(1), with melanoma having a relative incidence of 0.5% – 4% of all malignancies in this region (1,–,3). This site is the third most common primary location for melanoma after the skin and retina and yet only 0.4-1.6% of all primary melanomas arise here(3,4).

CASE REPORT

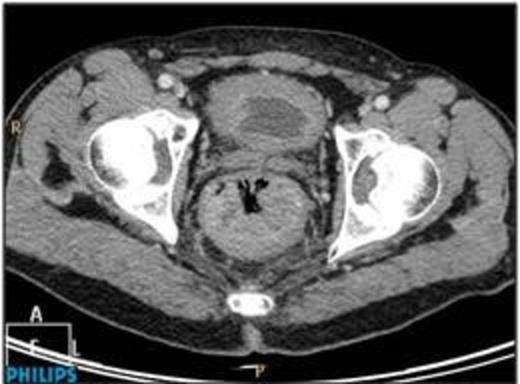

A 61 year old male was admitted having collapsed at home. He was pale, in sinus tachycardia, and normotensive with a palpable lesion per rectum. There was no hepatomegaly or regional lymphadenopathy. A colonoscopy, performed fourteen months earlier, showed tubular adenoma with low grade dysplasia in the transverse colon. Contrast CT abdomen and pelvis on admission revealed a large mass in the posterior rectum extending to the lateral wall (Figure 1).

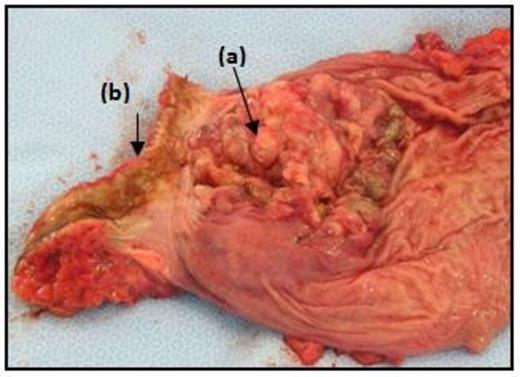

Repeat colonoscopy revealed a circumferential non-pigmented poorly-differentiated low rectal tumour at the anorectal junction. The patient proceeded to surgery and underwent an abdominoperineal resection with stoma formation, recovery was uneventful. The operative specimen revealed a large circular fungating lesion in the anorectum (Figure 2). Histologically, sections showed poorly-differentiated malignancy extending into surrounding connective tissue, with solid sheets of cells containing eosinophilic cytoplasm, focal pigmentation, S100 immunoreactivity and foci of in situ melanoma. Lymphovascular invasion was extensive. Regional lymph nodes showed reactive changes only. The isolated lesion and absence of a clinical history of primary melanoma elsewhere, together with the histological findings, favour a primary malignant melanoma.

DISCUSSION

Anorectal melanoma (ARM) may be difficult to identify grossly, and may be misdiagnosed as a haemorrhoid, rectal polyp, or occasionally following prolapse through the anal orifice with ulceration (2,5). The majority of lesions are polypoidal and pigmented (2), however many are amelanotic(16-53% ) (3,5).

Rectal bleeding is the commonest presentation along with other non-specific symptoms including local pain or discomfort, pruritus, tenesmus, palpable mass, prolapse, change in bowel habit and diarrhoea (1,3,5). At the time of diagnosis, up to 70% of patients with ARM have metastasised, probably secondary to the rich vascular and lymphatic channels in the anus (4). Mesorectal lymph nodes are involved in preference to inguinal lymph nodes in contrast to squamous cell carcinoma of the anus(4). Distant metastases include liver, lung, brain and bones (2). ARM has a clear female predominance(1), percentages varying from 54 – 76% (5), and most commonly presents in the 5th to 6th decade of life (1,5).

Immunohistochemical markers help to establish the diagnosis as features may be very similar to cutaneous melanoma (CM). Helmke et al identified that primary ARM is more likely to be positive for protein DMBT1 (70%) than CM (23%) (6). ARM is a mucosal melanoma and displays a remarkably different course and prognosis to CM, therefore making distinction between the two of upmost importance (5).

Optimal treatment is controversial due to a lack of randomized controlled trials and the rarity of the condition (2,5). Traditionally abdominoperineal resection (APR) with bilateral inguinal lymphadenectomy was performed, however the latter lacks evidence and is questionable given that nodal disease in ARM is thought not to carry the same significance as for CM (2,7).

Radical surgery has been challenged with wide local excision (WLE) when technically feasible with the goal of minimizing morbidity (7). WLE proves to have a quicker recovery, is a less invasive procedure with minimal impact on bowel, urinary and sexual function, and there is no indication for stoma formation (3,8). Patients report better quality of life with WLE than APR. Some studies provide supporting evidence for APR showing improved long term survival over WLE (7), while others show no difference (3). Yap et al found no statistically significant survival advantage for APR over WLE with patients compared by stage. Other authors propose there is no advantage to either approach as treatment of the primary tumour does not influence the systemic course of the disease (3,8). All studies indicate that relapse is usually distant and lethal with 75% of patients having disease recurrence despite the extent of resection (3,5).

APR should be undertaken only when WLE is not amenable to local excision (if tumour is circumferential or involves notable portion of the anal sphincter) or for palliative reasons in the presence of large obstructing tumours (2,5,7). APR is advocated for bulky lesions (thickness greater than 4mm) to achieve local control of disease and symptoms and to avoid complications and for recurrent disease or more advanced cases (8,9). WLE is proposed as the treatment of choice for early stage disease (9). Laparoscopic approach to APR may be beneficial in terms of reduced morbidity (2).

When adjuvant therapy is used with local excision it reduced mortality (7). Radiation may offer possibilities for future therapy (2). In our case no adjuvant therapy was given.

Despite the low rates of regional relapse and with 70% of patients presenting with localised and apparently curable disease (3), the prognosis is poor. Outcome is not predicted by lymphovascular invasion, ulceration or nodal status or related to the presence of melanin or in situ melanoma (3). Tumour necrosis, tumour size >20mm and thickness (Breslow >2mm) are associated with disease recurrence and represent a more aggressive tumour with worse outcomes (2,3). Other factors associated with poorer prognosis include duration of symptoms > 3 months, tumour perineural invasion, presence of inguinal lymph nodes, and amelanotic melanoma on histology (2).

The median survival in most patients ranges from 12 to 24 months (1,7), and five year survival is between 10-22% (1,2). This is in vast contrast to primary CM which has an 80% 5 year survival rate (3). Mortality in the majority of patients with ARM is due to distant metastases (1,3). Compared to CM, stage of disease has not been found to be a significant prognostic factor for ARM(2). Anorectal melanoma has a poor prognosis with early dissemination despite aggressive surgical and adjuvant treatment (4).