-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

MJ Lin, C Sinclair, Retropharyngeal haematoma – an unusual cause of airway obstruction, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2011, Issue 10, October 2011, Page 5, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/2011.10.5

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Retropharyngeal haematoma is a rare and potentially fatal cause of airway obstruction. The treatment of retropharyngeal haematoma is contentious. We report a case of an 84 year old woman on aspirin and warfarin who developed a retropharyngeal haematoma following minor blunt head and neck trauma. The patient presented insidiously with Capp’s triad and developed delayed airway obstruction necessitating emergency fibreoptic endoscopic intubation. Both tracheostomy and surgical drainage were avoided and she recovered well.

INTRODUCTION

Retropharyngeal haematoma is a rare and potentially fatal cause of airway obstruction. Management is controversial. We report a case of a female patient on aspirin and warfarin who developed a retropharyngeal haematoma following minor blunt head and neck trauma.

CASE REPORT

An 84 year old woman had a mechanical fall at ground level resulting in neck hyperextension. She complained of headache and neck pain. Her vital signs were normal. There were no neurological deficits and no dysphonia, stridor nor respiratory distress. A rigid cervical collar was applied and anterior neck and chest swelling and bruising were noted beneath this. Her International Normalized Ratio (INR) was 3.9.

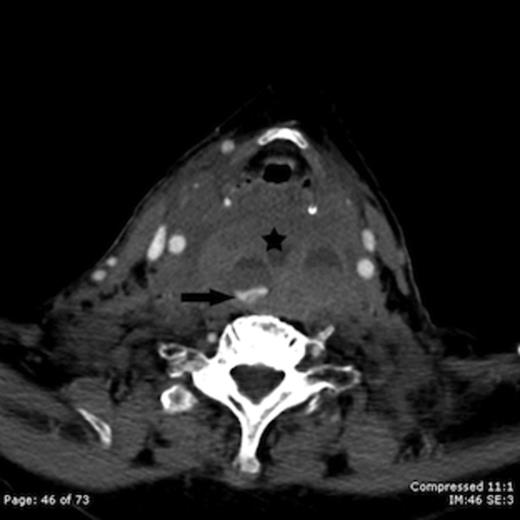

Computed tomography (CT) of the brain, neck and chest was performed. A massive retropharyngeal haematoma was observed extending between C2 and T4 vertebral body levels with displacement and compression of the trachea (Figure 1,2). There was no evidence of carotid, vertebral or internal jugular vein injury and no cervical fracture.

Contrast enhanced axial CT image taken at the level of the hyoid bone shows a large retropharyngeal haematoma (star) with active intravenous contrast extravasation (arrow)

Contrast enhanced sagittal CT image shows a large retropharyngeal haematoma (star) extending from the C2 vertebral level to below the level of the sternal notch with tracheal compression (arrow)

Nine hours from the time of injury the patient developed stridor. Awake fibreoptic endoscopic intubation was performed in the operating theatre with surgical airway backup. Although significant subglottic swelling was evident at intubation, a 6.5mm diameter endotracheal tube was successfully and atraumatically positioned into the distal trachea.

A four vessel angiogram was then obtained which revealed an actively bleeding branch of the right inferior thyroid artery. This small vessel was unable to be selected for safe coil embolisation. The patient was managed non-operatively with intravenous antibiotics, steroids and INR reversal. Over the coming days her neck swelling decreased and serial CT showed a reduction in size of the haematoma. She was extubated on day eight. Dysphagia necessitated nasogastric feeding for a further week and mild dysphonia persisted for two weeks. The patient otherwise made a good recovery, returning to her previous level of function by six weeks. Follow up CT at six weeks showed the haematoma to have completely resolved.

DISCUSSION

Aetiological factors implicated in retropharyngeal haematoma include blunt head and neck trauma, cervical spine injury, anticoagulation, bleeding diatheses and tumors. Most cases are thought to be due to bleeding from vessels covering the anterior longitudinal ligament.(2) Less commonly bleeding has been reported to originate from the thyrocervical trunk (3) as was likely the situation in this case.

The classic clinical presentation comprises Capp’s triad of airway compression, displacement of the trachea anteriorly and bruising of the neck and chest.(1) However, the clinical presentation is highly variable and may range from mild sore throat to hoarseness, dysphagia, odynophagia, dyspnoea or stridor.(1,–,5) An asymptomatic interval between time of injury and onset of stridor has been described(4) as in this case.

The treatment of retropharyngeal haematoma is contentious. The first step is to secure the airway if there is any evidence of airway obstruction. The haematoma may distort the anatomy of the upper airway making visualization of the cords difficult. Oral intubation may be particularly challenging especially if cervical fracture cannot be excluded. A surgical airway is advocated by some authors as the preferred method because endosopic intubation may be difficult and carry a higher risk of perforating the haematoma.(3) We elected to trial an awake endoscopic intubation method with tracheostomy equipment available if required. This intubation method allowed direct visualization of the laryngeal anatomy with minimal manipulation of the haematoma whilst maintaining cervical spine alignment.

With the airway secured, most patients are successfully managed conservatively with observation, supportive treatment and monitoring with serial CT. The haematoma usually resolves but can take four weeks or more.(5) Surgical evacuation or transoral aspiration is generally reserved for a haematoma that is rapidly expanding, impeding mechanical ventilation or failing to resolve. Although surgery may lead to an earlier extubation and recovery, it does carry an increased risk of infection. (1)

We have presented a case of a large retropharyngeal haematoma in an elderly anticoagulated patient following minor blunt head and neck trauma. The patient presented insidiously with Capp’s triad and developed delayed airway obstruction necessitating emergency fibreoptic endoscopic intubation. Both tracheostomy and surgical drainage were avoided and she recovered well. Conservative management may be appropriate in patients with non expanding haematomas that show improvement on serial CT.