-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Alessandro Verbo, Mattia Angelo Bez, Danilo Di Giorgio, Iacopo Verbo, A rare case of deep fibrous histiocytoma with low-grade myxoid and dedifferentiated liposarcoma features: clinical, radiological, and histopathological insights, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2026, Issue 1, January 2026, rjag015, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjag015

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Deep fibrous histiocytoma (DFH), also termed deep benign fibrous histiocytoma, is an uncommon fibroblastic neoplasm that typically arises in the dermis or subcutis. Occurrence in deep soft tissues is rare and retroperitoneal presentation is exceptional. Distinguishing DFH from soft tissue sarcomas can be challenging when lesions show atypical morphology or focal lipogenic change. We report a giant retroperitoneal DFH displaying low-grade myxoid and dedifferentiated liposarcoma-like area and summarize diagnostic pearls and management considerations. A 53-year-old man presented with postprandial dyspepsia and increased bowel movements. Imaging revealed a multilobulated retroperitoneal mass (35 × 32 × 18 cm) displacing the inferior vena cava, aorta, and bowel loops, with the left kidney ectopically located in the right paramedian pelvis. Through a xipho-pubic laparotomy, a well-encapsulated 12-kg tumor was excised en bloc without rupture. Histology showed a spindle-cell proliferation with storiform and meningothelial-like architecture consistent with DFH, with foci of low-grade myxoid change and areas mimicking dedifferentiated liposarcoma. Immunohistochemistry demonstrated CD34 positivity and negativity for S100 and smooth muscle actin in the fibrohistiocytic component. The early postoperative course was uneventful. Retroperitoneal DFH is a diagnostic mimic of liposarcoma and other sarcomas. Correlation of morphology with an appropriate immunophenotype and clinical-radiologic context is essential to avoid overtreatment. Complete surgical excision is the mainstay of therapy; long-term surveillance is advisable given the deep location and size.

Introduction

Deep fibrous histiocytoma (DFH) is a benign fibroblastic/myofibroblastic neoplasm within the so-called fibrohistiocytic tumor group of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of soft tissue and bone tumors. While conventional benign fibrous histiocytoma (dermatofibroma) is common in the skin, DFH accounts for a minor subset and arises in subcutis or deep soft tissue where it may grow to a substantial size. Retroperitoneal involvement is exceedingly rare and may be clinically indistinguishable from primary retroperitoneal sarcomas. Contemporary WHO updates (5th edition) emphasize the heterogeneous morphology and the need for integration of histology, immunohistochemistry, and, when appropriate, molecular testing to distinguish benign fibroblastic tumors from sarcomas. In deep locations, DFH may display increased cellularity, myxoid change, or even areas that mimic low-grade lipogenic neoplasia, blurring the boundaries with myxoid liposarcoma or dedifferentiated liposarcoma (DDLPS). Misclassification can lead to unnecessary multimodal therapy and anxiety regarding prognosis.

We describe a giant retroperitoneal DFH with areas resembling low-grade myxoid and DDLPS and outline the diagnostic approach, operative strategy, and rationale for surveillance. We also provide a concise review of recent literature to contextualize this unusual presentation.

Case presentation

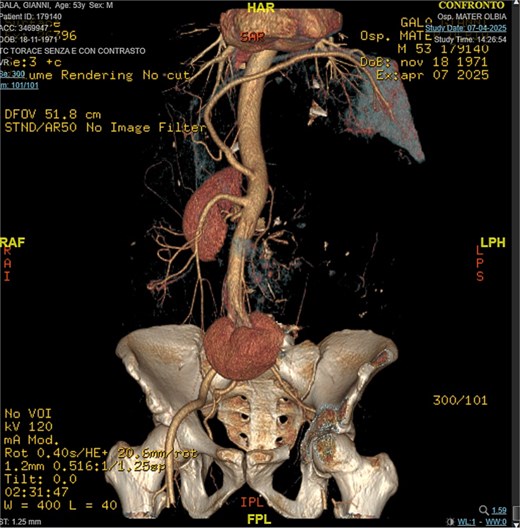

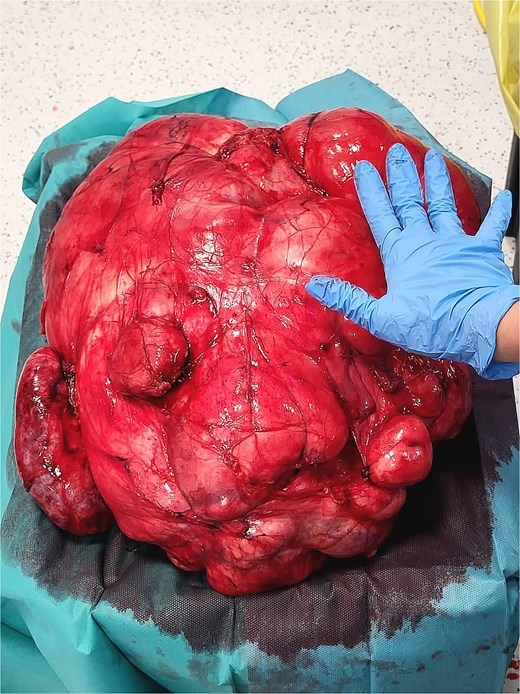

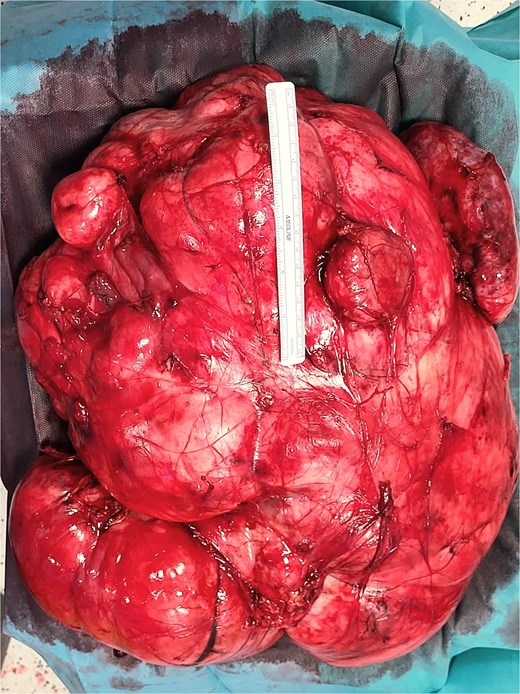

A 53-year-old man, ex-smoker and occasional alcohol consumer, reported several months of postprandial dyspepsia and increased bowel movements (3–4 per day), without weight loss or systemic symptoms. Physical examination revealed a distended, somewhat tense abdomen without focal tenderness. Laboratory tests, including complete blood count, biochemistry, and inflammatory markers, were within normal limits. Cross-sectional imaging demonstrated a multilobulated, predominantly solid retroperitoneal mass measuring 35 × 32 × 18 cm. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed displacement—but no frank invasion—of the inferior vena cava and aorta, encasement of mesenteric vessels, and compression of bowel loops. A notable anatomic variant was an ectopic left kidney located in the right paramedian pelvis. No distant lesions were identified (Figs 1 and 2). Three-dimensional CT angiography delineated the relationship with major vessels and aided operative planning (Fig. 3). After multidisciplinary discussion, primary surgical resection was favored given the well-circumscribed nature of the mass, the absence of metastatic disease, and the patient’s symptoms. Through a midline xipho-pubic laparotomy, a well-encapsulated, firm, tan-white mass occupying most of the retroperitoneal cavity was exposed. Sharp and blunt dissection allowed complete en bloc excision without capsular violation. Estimated blood loss was modest and no vascular reconstruction was required. Grossly, the specimen weighed approximately 12 kg and showed multinodular architecture with focal myxoid areas.

Pathologic findings

Histopathologic examination revealed a spindle-cell proliferation arranged in storiform and meningothelial-like whorls in a collagenous stroma, with scattered foamy histiocytes and occasional giant cells. Foci of low-grade myxoid change were present. In addition, discrete areas exhibited increased cellularity with short fascicles and atypical pleomorphic cells lacking adipocytic differentiation but mimicking the dedifferentiated component of liposarcoma. Necrosis was absent, and mitotic activity was low (up to 2 per 10 high-power fields). Immunohistochemically, the fibrohistiocytic component was positive for CD34 and negative for S100 and smooth muscle actin (SMA); factor XIIIa highlighted scattered dendritic cells. The overall morphologic and immunophenotypic profile supported the diagnosis of DFH with low-grade myxoid areas and regions mimicking DDLPS. Margins were free of tumor. Representative intraoperative photographs are shown in Figs 4 and 5.

Differential diagnosis and immunohistochemistry

The principal differential diagnoses in a deep retroperitoneal mass with spindle-cell morphology and myxoid change include myxoid liposarcoma, DDLPS, solitary fibrous tumor (SFT), desmoid-type fibromatosis, and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma. Myxoid liposarcoma typically shows a delicate plexiform capillary network and lipoblastic differentiation and is often DDIT3-rearranged; DDLPS commonly arises in the retroperitoneum and contains well-differentiated lipogenic areas with MDM2 and CDK4 .amplification and nuclear immunoreactivity. SFT usually shows patternless architecture with staghorn vasculature and STAT6 nuclear positivity. Desmoid-type fibromatosis displays long sweeping fascicles of uniform myofibroblasts with nuclear β-catenin positivity. DFH, in contrast, often exhibits a storiform/whorled pattern, variable myxoid stroma, and a benign immunoprofile with negativity for S100 and myogenic markers; CD34 expression can be seen but is not specific. In the present case, the lack of definitive lipogenic differentiation, negativity for S100 and SMA, absence of STAT6 nuclear staining, and the overall low-grade morphology favored DFH over sarcoma. When available, ancillary MDM2 amplification testing may assist in excluding DDLPS in challenging cases; however, clinicoradiologic-pathologic correlation remained decisive here.

Postoperative course and follow-up

The postoperative course was uneventful. The patient resumed oral intake on postoperative day 2 and was discharged on day 6. At early outpatient review (6 weeks), he reported resolution of dyspepsia and normalization of bowel habits. Given the deep location and immense size, we recommended long-term clinical and imaging surveillance to monitor for local recurrence. Although DFH is biologically benign, incomplete excision of deep-seated lesions may predispose to recurrence; conversely, metastasis is exceptionally rare.

Discussion

This case highlights diagnostic and management challenges posed by deep-seated fibroblastic tumors in the retroperitoneum. The retroperitoneum is a prototypical site for primary sarcomas, particularly well-DDLPS, leiomyosarcoma, and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma; consequently, large masses are often presumed malignant [4]. DFH in deep sites can deviate from classic cutaneous presentations and display increased cellularity, myxoid change, and areas that simulate the dedifferentiated component of liposarcoma, complicating histologic interpretation [1–3]. The stakes of misdiagnosis are high: overcalling a benign lesion as sarcoma can prompt unnecessary systemic therapy or morbid surgery, whereas missing an aggressive sarcoma delays definitive treatment. Contemporary guidance underscores integrating morphology, immunohistochemistry, and, where indicated, molecular testing. MDM2 and CDK4 amplification assessed by FISH or immunohistochemistry supports a diagnosis of DDLPS; their absence, in the appropriate morphologic context, weighs against DDLPS [1, 2, 4]. CD34 expression in DFH is variable and nonspecific, whereas S100 highlights neural and adipocytic differentiation and tends to be negative in DFH [1, 2]. In our case, storiform/meningothelial-like architecture, low mitotic rate, negativity for S100 and SMA, and the clinicoradiologic appearance supported DFH. Imaging was informative: despite massive size, the lesion was well circumscribed and compressive rather than infiltrative, with major vessels displaced rather than invaded. From a surgical standpoint, the goal is complete macroscopic resection with an intact capsule and negative margins while preserving function, akin to principles used in retroperitoneal sarcoma surgery [4]. Preoperative three-dimensional vascular mapping aided planning and helped avoid vascular reconstruction. Given the benign biology, adjuvant radiotherapy or systemic therapy is not indicated after complete resection. Because deep-seated DFH may recur after incomplete excision, interval imaging (e.g. CT or MRI) in the first 2–3 years is reasonable, then symptom-driven thereafter, aligning follow-up with lesion size, location, and margin status. Recent reports continue to clarify the spectrum of DFH in unusual anatomical sites and reinforce the importance of targeted immunohistochemistry and, when necessary, molecular assays [1–3]. Advances in retroperitoneal sarcoma care emphasize how precise classification informs treatment selection and follow-up, underscoring the value of multidisciplinary review for large retroperitoneal masses [4, 5].

Conclusion

Retroperitoneal DFH is an exceptionally rare benign tumor that may mimic liposarcoma histologically and radiologically, especially when low-grade myxoid areas and DDLPS-like regions are present. Close clinicopathologic correlation is essential to avoid overtreatment. Complete surgical excision yields excellent short-term outcomes; prudent long-term surveillance is recommended for deep-seated, very large lesions.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

No specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors was received for this work.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. This is a single case report that did not require formal ethical committee approval. Written informed consent for participation was obtained from the patient.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of this case report and accompanying images was obtained from the patient.

References

- actins

- aorta

- immunohistochemistry

- smooth muscle

- defecation

- cd34 antigens

- dyspepsia

- histiocytoma, benign fibrous

- intestines

- laparotomy

- liposarcoma

- postprandial period

- pubis

- retroperitoneal space

- sarcoma

- inferior vena cava

- diagnosis

- diagnostic imaging

- histology

- neoplasms

- pelvis

- surveillance, medical

- subcutaneous tissue

- kidney, left

- dedifferentiated liposarcoma

- excision

- histopathology tests

- overtreatment

- soft tissue