-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Hany Habib, Himsikhar Khataniar, Chandan Dash, Kojo-Frimpong B Awuah, Sheena Mago, Abhijit Kulkarni, Clip-choledocholithiasis: a case of migrated surgical clip causing choledocholithiasis, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2026, Issue 1, January 2026, rjag004, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjag004

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Post-cholecystectomy clip migration is a rare but significant complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy that can manifest years after the initial surgery. We report the case of a 56-year-old female who presented with chronic upper abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting eight years following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Laboratory investigations demonstrated markedly elevated liver enzyme levels, and imaging studies revealed a stone in the common bile duct. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography identified a surgical clip embedded within the stone, serving as a nidus for stone formation. Successful treatment was achieved through biliary sphincterotomy and stone retrieval, resulting in complete symptomatic relief and normalization of liver function tests. This case highlights the importance of considering clip migration as a potential etiology in post-cholecystectomy patients presenting with unexplained biliary symptoms, even many years after the initial surgical procedure.

Introduction

Since its inception in 1985, laparoscopic cholecystectomy has rapidly evolved from a novel procedure to the preferred treatment for gallstone disease, offering shorter recovery times and reduced postoperative pain compared with open surgery [1, 2]. Despite its favorable outcomes, complications, such as bile duct injuries, remain a major concern [3]. Clip migration, although rare, is a serious complication wherein surgical clips used during the procedure migrate into the common bile duct and can serve as a nidus for stone formation, potentially leading to obstruction [4]. We present the case of a 56-year-old patient who experienced metal clip migration 8 years after laparoscopic cholecystectomy, which was successfully identified and treated using endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

Case report

A 53-year-old female with a history of laparoscopic cholecystectomy 8 years prior, presented to our hospital with several months of chronic upper abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Previously, her symptoms were suspected to be ulcer-related, and she was treated with a proton-pump inhibitor. However, she did not experience symptomatic improvement.

Physical examination revealed that she was afebrile and her abdomen was soft with mild diffuse tenderness, but without rebound or guarding. Laboratory results indicated a normal white blood cell count of 9.91 × 109/L, but elevated liver function tests: alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 769 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase at 1543 U/L, total bilirubin at 1.5 mg/dl, and gamma-glutamyl transferase at 508 U/L. Her lipase level was within the normal range (35 U/L).

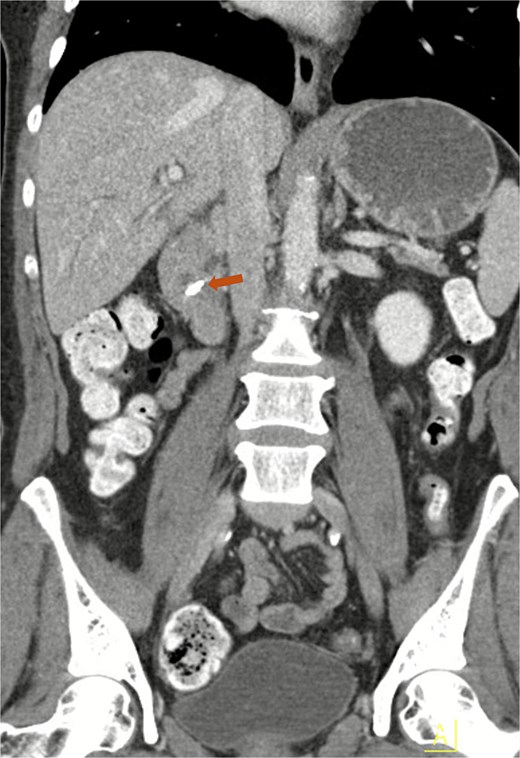

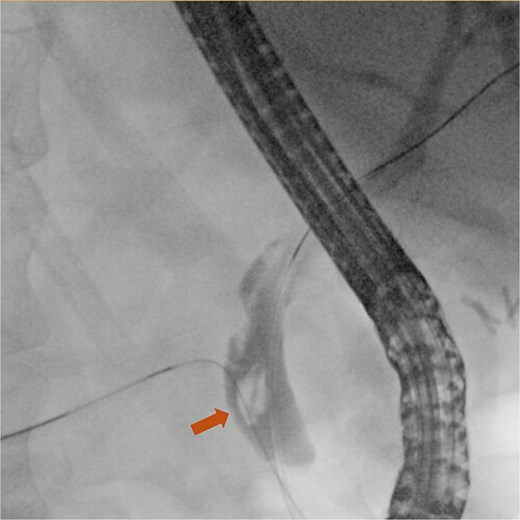

Contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a surgically absent gallbladder. A surgical clip was identified in the region of the ampulla of Vater, and a 4 mm stone was located in the distal common bile duct just proximal to the ampulla (Fig. 1). Subsequently, ERCP was performed, during which a 6 mm brown pigment stone was identified in the middle third of the main bile duct. In addition, a metallic foreign object resembling a surgical clip was noted within the stone (Fig. 2). Biliary sphincterotomy was performed using a traction sphincterotome and electrocautery. The biliary tree was then swept with a 15 mm balloon starting at the bifurcation, and the sludge was removed from the duct. The stone was successfully retrieved using Roth Net (Fig. 3), and a plastic stent was placed in the ventral pancreatic duct. The patient’s liver function test results improved following the procedure, and the patient was discharged. Passage of the pancreatic duct stent was confirmed by abdominal radiography.

Contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen demonstrating a migrated clip in the common bile duct (arrow).

ERCP fluoroscopy image showing a common bile duct stone (arrow).

Discussion

Foreign materials lodged in the bile ducts can serve as a nidus for choledocholithiasis formation. Stones forming on iatrogenic materials used to close ducts, such as both absorbable and non-absorbable sutures and metallic clips, have been reported in the literature [4]. Calculi formed around foreign bodies in the bile ducts vary in composition. Brown pigment stones, composed primarily of calcium bilirubinate and calcium palmitate, predominate, while cholesterol, mixed, and black pigment stones have also been documented [5].

Post-cholecystectomy clip migration (PCCM) is an exceedingly rare complication that can occur after both open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy, first described in 1979 and 1992, respectively [6, 7]. Despite the increasing frequency of laparoscopic cholecystectomies, reported instances of PCCM have been decreasing [8]. Its exact prevalence remains unestablished, with fewer than 100 cases reported in the literature, although a recent literature review found 68 cases in the English literature [8]. The interval between cholecystectomy and clinical presentation varies widely, from 2 weeks to 35 years [4]. A recent case report with a literature review by Tanimu et al. found the mean age of affected patients to be 61.5 years, ranging from 31 to 88 years, with a slight female predilection (62%) [8]. The most common clinical presentations are biliary colic, jaundice, nausea, vomiting, and fever [8]. The diagnosis should generally be straightforward, as the metallic clip is typically visible on radiographic images. In the present case, the patient presented with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Laboratory investigations revealed elevated liver function, and while the initial CT scan showed a stone in the common bile duct, it did not identify the clip. Subsequent ERCP was required to reveal the embedded clip and to successfully remove it.

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the clip migration. Kitamura et al. hypothesized that compression of the cystic duct by surrounding tissues leads to its inversion into the common bile duct along with attached clips. This inversion results in necrosis, which facilitates clip migration [9]. Other contributing factors include improper clip placement, short cystic duct or cystic artery, and ischemic damage leading to necrosis of the cystic duct [5]. The vast majority of documented PCCM cases involve non-absorbable metallic clips, likely reflecting their widespread adoption in laparoscopic cholecystectomy compared to absorbable alternatives [4].

PCCM management is typically minimally invasive. ERCP was the preferred treatment modality, with a success rate of 84.5%. However, if ERCP fails, surgical intervention is necessary. An alternative, though less commonly used method, is percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography [10].

In conclusion, post-cholecystectomy clip migration is a rare but serious complication that can arise years after surgery, with symptoms such as biliary colic or cholangitis. ERCP is the modality of choice for both diagnosis and treatment. Given its infrequency, further research is essential to ensure an increase in the global knowledge of this complication. Additional studies are needed to elucidate the risk factors and mechanisms underlying clip migration, which will aid in preventing its occurrence and in improving patient outcomes.

Acknowledgements

This case was presented at the ACG Conference in October 2024. https://doi.org/10.14309/01.ajg.0001040188.46827.72

Conflicts of interest

No conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors have no funding sources to declare.

Ethical approval

No ethical approval is required.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of details of their medical case and any accompanying images.

Guarantor

Hany Habib is the article guarantor.

References

Keus F, de Jong JA, Gooszen HG et al. Laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy for patients with symptomatic cholecystolithiasis.

Ng DYL, Petrushnko W, Kelly MD. Clip as nidus for choledocholithiasis after cholecystectomy-literature review.

Tanimu S, Coombs RA, Tanimu Y et al. Cholecystectomy clip-induced biliary stone: Case report and literature review.

- abdominal pain

- cholecystectomy

- choledocholithiasis

- endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

- calculi

- common bile duct

- liver function tests

- surgical procedures, operative

- diagnostic imaging

- laparoscopic cholecystectomy

- nausea and vomiting

- sphincterotomy

- liver enzyme

- transaminitis

- causality

- surgical clips