-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Yogesh Rawat, Mohd Sadik Akhtar, Ankur Rawat, Praveen Raj, Isolated pancreatic tail and splenic hilum tuberculosis: a rare case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 9, September 2025, rjaf754, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf754

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Abdominal tuberculosis (TB) is a rare extrapulmonary manifestation, with pancreatic and splenic involvement being extremely uncommon and often misdiagnosed as malignancy. We present the case of a 22-year-old female with chronic epigastric pain, weight loss, and fever. Imaging revealed a necrotic lymph node mass near the pancreatic tail and splenic hilum with splenic infarction. Fine-needle aspiration cytology confirmed TB, and the patient responded well to anti-tubercular therapy, avoiding surgical intervention. This case underscores the importance of considering TB in the differential diagnosis of upper abdominal masses in endemic regions to prevent unnecessary surgeries.

Introduction

Abdominal tuberculosis (TB), an extrapulmonary manifestation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, accounts for ~5% of all TB cases and poses significant diagnostic challenges due to its nonspecific presentation [1]. Among abdominal TB cases, involvement of the pancreas and spleen is extremely rare, with pancreatic TB constituting <5% of abdominal TB presentations [2]. Clinically and radiologically, this condition often mimics malignancy, leading to unnecessary surgical interventions if not identified early.

Here, we report a rare case of a 22-year-old woman presenting with a pancreatic tail mass and associated splenic infarction, which was ultimately diagnosed as abdominal TB based on biopsy findings.

Case report

A 22-year-old female presented with a 4-month history of epigastric pain, gradually progressive and radiating to the back. The pain was dull, aching, and partially relieved by medication. She also reported intermittent vomiting, low-grade fever for 1.5 months, loss of appetite, and significant weight loss. Her medical history included irregular menses, whitish vaginal discharge, and intake of oral contraceptive pills. Importantly, she had a history of contact with a sibling suffered from pulmonary TB 6 years back.

On examination, the patient appeared cachectic with a body mass index of 15.55 kg/m2, pallor, and no lymphadenopathy. Vital signs were stable. Abdominal examination revealed mild tenderness in the left upper quadrant without organomegaly or ascites. Laboratory findings: Hemoglobin: 8.3 g/dl, Platelets: 1 07 000/mm3, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR): 40 mm/hour, and renal and liver function were within normal limits. Her chest X-ray was normal, which did not show any cavities, lymphadenopathy, or any other TB changes. Her sputum study was normal and did not show any TB organism.

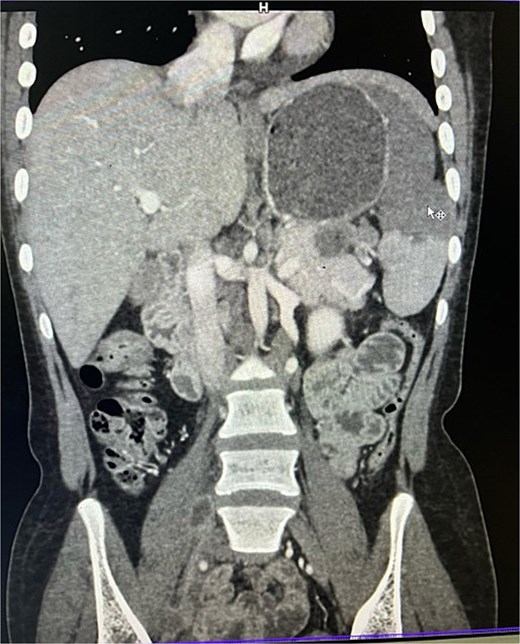

On imaging, ultrasonography showed a lobulated hypoechoic lesion in the region of the pancreatic tail and splenic hilum. This was very not conclusive, so a contrast-enhanced CT scan was planned, which revealed multiple necrotic, conglomerated lymph nodes (30 × 33 × 38 mm) near the splenic hilum and pancreatic tail, abutting the stomach and spleen, with maintained fat planes (Fig. 1). A splenic infarct involving a significant portion of the parenchyma was noted (Fig. 2), with multiple additional necrotic nodes along the retroperitoneum (paraaortic and iliac vessels) and mild pelvic free fluid. Then, CT-guided biopsy from the lymph nodal mass was planned, which showed moderately cellular smears showed caseous necrotic debris, lymphocytes, and clusters of epithelioid cells, suggestive of chronic necrotizing lesion consistent with TB.

Contrast enhanced computer tomography (CECT) abdomen showing necrotic lymph node mass near pancreatic tail and splenic hilum.

CECT abdomen showing splenic infarct involving significant portion of splenic parenchyma—except at the lower pole of spleen.

The patient was started on first-line anti-tubercular therapy (ATT) as per national guidelines. Splenectomy was considered but deferred due to preserved lower pole of the spleen and expected response to medical therapy. She was counseled about vaccination against encapsulated organisms if splenectomy became necessary later.

She was discharged once patient had pain relieved and was taking orally and was then treated on outpatient basis. After six weeks of ATT, the patient showed significant clinical improvement and weight gain. Currently, patient pain is fully relieved, and there is good weight gain.

Discussion

Pancreatic TB is an extremely rare entity, even in TB-endemic countries, due to the bactericidal nature of pancreatic enzymes [3]. It typically occurs through hematogenous spread or contiguous involvement from lymph nodes, and often presents as an abdominal mass mimicking a neoplasm [4]. Patients commonly present with abdominal pain, low-grade fever, weight loss, and sometimes obstructive jaundice [5]. CT imaging usually reveals hypodense lesions with central necrosis and peripheral enhancement, often associated with necrotic lymphadenopathy [6]. In our case, the imaging showed a mass near the pancreatic tail with extensive nodal involvement and splenic infarction, strongly mimicking lymphoma or malignancy. We had multiple differential diagnoses in mind while evaluating the patient, like pancreatic carcinoma, lymphoma, chronic pancreatitis, splenic abscess, or infarction.

Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is the gold standard for diagnosis, showing caseating granulomas with epithelioid cells. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for M. tuberculosis can further confirm the diagnosis [7]. The cornerstone of treatment is ATT for 6–9 months. Surgery is reserved for complications or diagnostic uncertainty [8]. Our patient responded well to medical therapy alone, avoiding unnecessary splenectomy or pancreatic resection.

Conclusion

Pancreatic and splenic TB is rare and often mimics malignancy, creating significant diagnostic challenges. Clinicians in TB-endemic regions should maintain a high index of suspicion in young patients presenting with upper abdominal masses and constitutional symptoms. Early use of imaging and FNAC enables accurate diagnosis and initiation of ATT, thereby avoiding unnecessary surgery and improving patient outcomes [1–3,6,8].

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.