-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Varsha Reddy, Shailesh Solanki, Ravi P Kanojia, Nitin J Peters, Jai K Mahajan, Rectal ectasia in children: challenges in management, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 9, September 2025, rjaf753, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf753

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Rectal ectasia is a condition characterized by significant dilatation of the rectum. It can be either primary or secondary to distal obstruction. The literature does not clarify the embryo-pathogenesis, diagnostic criteria, investigation protocols, or management strategies. A key aspect of diagnosis is to exclude medical causes of constipation and Hirschsprung's disease. Surgical management involves various interventions, but insufficient data support the literature. Here, we describe our experience with two children diagnosed with rectal ectasia. We discuss the presentation, diagnosis, surgical intervention, complications, and the rationale for selecting one procedure over another while reviewing the relevant literature.

Introduction

Rectal ectasia is a condition characterized by massive dilation of the rectum that can extend into various lengths of the colon. Swenson and Rathauser first described this dilatation in 1959 [1]. It can occur as a primary or secondary disease resulting from distal obstruction, like in cases of anorectal malformations (ARM) with fecalomas [2]. Primary ectasia (congenital) is rare but can lead to constipation that resists medical treatment in children. This condition is frequently misdiagnosed as Hirschsprung's disease (HD); the only way to exclude HD is to show functional ganglion cells upon biopsy. There is no established consensus in the literature regarding the diagnosis or management of rectal ectasia. In this report, we discuss the presentation and management of two children with primary rectal ectasia who were treated at our center.

Case 1

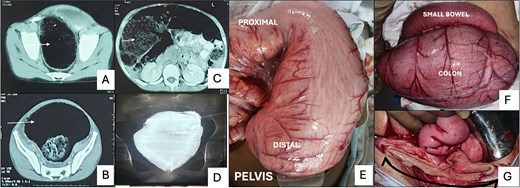

An 11-year-old male presented to the pediatric emergency department with complaints of abdominal distension and obstipation lasting for 10 days. The patient had a 6-year history of functional constipation as defined by the Rome IV criteria [3]. He had been using oral laxatives for this condition for 5 years. There was no history of delayed passage of meconium, and his neonatal and infantile periods were uneventful. Upon examination, the child appeared thin, with a − 1 z-score for height (140 cm) and weight (33 kg). The abdomen was grossly distended, with palpable fecalomas. On digital rectal examination, the rectum was loaded with hard stool, with normal anal sphincter tone. Medical causes of constipation, such as hypothyroidism, were ruled out. An abdominal X-ray revealed a grossly dilated large bowel with fecal loading, and a computed tomography (CT) scan showed a grossly dilated large bowel at the level of the pelvic brim (Fig. 1A and B). The child did not respond to initial conservative management.

(A) and (B) show a grossly dilated colon (white arrow) in the pelvis at the level of the pelvic brim and ischial spines. (C) Cross-sectional image on CT showing air and stool-filled colon (white arrow) displacing the small bowel loops to one side. (D) Contrast enema after 3 months of Hartmann’s procedure, demonstrating persistent dilatation of the rectal stump. (E) Intra-operative picture of Case 1 displays a severely dilated colon extending beyond the peritoneal reflection, lacking features typical of a pouch colon. (F) Intra-operative image of Case 2 showing gross dilatation of the colon in comparison to the small bowel. (G) Illustrates the sizeable luminal caliber of the distal stump (black arrow) after resection at the peritoneal reflection.

The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy; intraoperative findings revealed a normal small bowel, ascending colon, and transverse colon, with abrupt, gross dilatation of the sigmoid colon and rectum beyond the peritoneal reflection (Fig. 1E). Resection of the dilated segment above the peritoneal reflection was done, and the Hartmann procedure was performed. The patient experienced a symptom-free postoperative period. Biopsy results indicated the presence of ganglion cells throughout the resected segment. A subsequent rectal biopsy confirmed the presence of ganglion cells. A barium enema later showed a grossly dilated pouch-like structure (Fig. 1D). After 7 months, a Duhamel pull-through (with Martin's modification) was performed to restore bowel continuity, with an uneventful immediate postoperative course.

Two months later, the patient presented again to the emergency department with abdominal distension and constipation for 4 days. On examination, the abdomen was grossly distended. A digital rectal examination revealed fecal loading with no residual spur. The patient was operated on after the failure of conservative management for 48 h. The entire colon was grossly distended till the peritoneal reflection. A diversion sigmoid colostomy was created. Distal cologram in the postoperative period appeared as a hugely dilated distal pull-through bowel. Eight months later, a standard Swenson pull-through was performed, i.e. resection of the rectum and colo-anal anastomosis with a covering ileostomy, which was closed after 3 months. The patient has been doing well for 18 months, post-restoration of bowel continuity, with no symptoms of enterocolitis.

Case 2

A 9-year-old male presented with abdominal pain, distension, and a 2-week history of non-passage of stool. The patient had a 4-year history of constipation and required laxatives and enemas. Examination revealed a grossly distended abdomen with palpable bowel loops with rectum loaded with stool. A CT scan from an outside center indicated a significantly dilated sigmoid colon with a diameter of 16 cm (Fig. 1B and C).

During exploration, the sigmoid colon appeared disproportionately dilated compared to the descending colon, (around five times the diameter) (Fig. 1F). The dilated segment was resected up to the peritoneal reflection, which was also significantly dilated (Fig. 1G) at the lower end, and a Hartmann procedure was performed. Biopsy results showed no significant abnormalities in the preserved ganglion plexus and muscle layers. In the postoperative period, a contrast enema revealed a pouch-like configuration of the dilated rectum. A rectal biopsy was done, suggesting the presence of ganglion cells.

Bowel continuity was restored after 6 months, during which a complete resection of the dilated rectum and Swenson pull-through of the proximal colon with a colo-anal anastomosis was performed. A diversion ileostomy was also performed during the pull-through, which was closed successfully after 3 months. The patient was doing well at a 1-year follow-up and was experiencing regular bowel movements.

Discussion

Rectal ectasia is a rare pathological entity, with its exact incidence remaining undefined within the Indian population. There are no clear-cut guidelines or investigation protocols to diagnose the condition, and therefore, many fewer cases have been reported. And so the medical management and surgical intervention are also in a gray area for the condition. It appears to exhibit a male predilection, as observed in both of our reported cases. The primary or congenital form of rectal ectasia is hypothesized as a defect from embryological maldevelopment of the cloacal structure. This theory is supported by Brent and Stephen’s observations, which documented neonatal presentations of megarectum associated with megacystis, suggesting a common embryological origin [4]. Alternative hypotheses concerning the etiology include: aberrant overdevelopment of the primitive rectal ampullae, failure of regression and subsequent incorporation of the embryonic tailgut into the rectal architecture, primary neuromuscular dysfunction leading to hypomotility of the distal bowel, resulting in progressive rectal dilatation and anatomical anomalies such as mid-anal sphincteric defects. Approximately 2%–5% of ARM have been associated with concomitant rectal ectasia, indicating a subset within the broader ARM spectrum that may involve significant structural and functional bowel anomalies.

The clinical symptomatology is primarily characterized by chronic constipation, typically refractory to standard medical management, especially in older pediatric populations. Gattuso et al. have noted an earlier clinical onset in cases of idiopathic megarectum as opposed to isolated megacolon [5]. In neonates, presentations may include progressive abdominal distention and urinary dysfunction attributable to extrinsic compression of the bladder.

In children with ARM and associated rectal ectasia, overflow fecal incontinence is a common complaint, often resistant to rectal washout therapy. A critical differential diagnosis includes HD, particularly in cases where there is delayed passage of meconium (Table 1). In our cohort, both patients presented within the first decade of life, manifesting severe, functionally debilitating constipation that failed to respond to conservative measures and laxatives.

| Hirschsprung’s disease . | Rectal ectasia . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptomatology | Neonatal period | Delayed passage of meconium, passing stool only with stimulation | Non specific |

| Childhood | Constipation, enema dependent | Constipation, poor response to enemas leading to encopresis | |

| Rectal examination | Anal canal is empty and hard stool felt at the tip of finger | Stool soiling in the perianal area. Anal canal is filled with stool. | |

| Contrast enema | Reversal of recto-sigmoid ratio, retention of contrast 24 h later | Retention of contrast may be seen but no recto-sigmoid reversal | |

| Intra-operative | Grossly dilated sigmoid colon and rectum till peritoneal reflection with tapering downward | Grossly dilated sigmoid and rectum till the anal canal. No tapering seen. Distal stump has a very large caliber lumen while performing Hartmann’s procedure, usually not seen in HD. | |

| Histopathology | -Absence of ganglion cells -Presence of neuromatoid hyperplasia | -Presence of ganglion cells -Absence of neuromatoid hyperplasia | |

| Hirschsprung’s disease . | Rectal ectasia . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptomatology | Neonatal period | Delayed passage of meconium, passing stool only with stimulation | Non specific |

| Childhood | Constipation, enema dependent | Constipation, poor response to enemas leading to encopresis | |

| Rectal examination | Anal canal is empty and hard stool felt at the tip of finger | Stool soiling in the perianal area. Anal canal is filled with stool. | |

| Contrast enema | Reversal of recto-sigmoid ratio, retention of contrast 24 h later | Retention of contrast may be seen but no recto-sigmoid reversal | |

| Intra-operative | Grossly dilated sigmoid colon and rectum till peritoneal reflection with tapering downward | Grossly dilated sigmoid and rectum till the anal canal. No tapering seen. Distal stump has a very large caliber lumen while performing Hartmann’s procedure, usually not seen in HD. | |

| Histopathology | -Absence of ganglion cells -Presence of neuromatoid hyperplasia | -Presence of ganglion cells -Absence of neuromatoid hyperplasia | |

| Hirschsprung’s disease . | Rectal ectasia . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptomatology | Neonatal period | Delayed passage of meconium, passing stool only with stimulation | Non specific |

| Childhood | Constipation, enema dependent | Constipation, poor response to enemas leading to encopresis | |

| Rectal examination | Anal canal is empty and hard stool felt at the tip of finger | Stool soiling in the perianal area. Anal canal is filled with stool. | |

| Contrast enema | Reversal of recto-sigmoid ratio, retention of contrast 24 h later | Retention of contrast may be seen but no recto-sigmoid reversal | |

| Intra-operative | Grossly dilated sigmoid colon and rectum till peritoneal reflection with tapering downward | Grossly dilated sigmoid and rectum till the anal canal. No tapering seen. Distal stump has a very large caliber lumen while performing Hartmann’s procedure, usually not seen in HD. | |

| Histopathology | -Absence of ganglion cells -Presence of neuromatoid hyperplasia | -Presence of ganglion cells -Absence of neuromatoid hyperplasia | |

| Hirschsprung’s disease . | Rectal ectasia . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptomatology | Neonatal period | Delayed passage of meconium, passing stool only with stimulation | Non specific |

| Childhood | Constipation, enema dependent | Constipation, poor response to enemas leading to encopresis | |

| Rectal examination | Anal canal is empty and hard stool felt at the tip of finger | Stool soiling in the perianal area. Anal canal is filled with stool. | |

| Contrast enema | Reversal of recto-sigmoid ratio, retention of contrast 24 h later | Retention of contrast may be seen but no recto-sigmoid reversal | |

| Intra-operative | Grossly dilated sigmoid colon and rectum till peritoneal reflection with tapering downward | Grossly dilated sigmoid and rectum till the anal canal. No tapering seen. Distal stump has a very large caliber lumen while performing Hartmann’s procedure, usually not seen in HD. | |

| Histopathology | -Absence of ganglion cells -Presence of neuromatoid hyperplasia | -Presence of ganglion cells -Absence of neuromatoid hyperplasia | |

A fundamental prerequisite for diagnosing primary rectal ectasia is the exclusion of distal mechanical obstruction. Although cross-sectional imaging modalities often provide nonspecific findings—typically a markedly dilated colon with significant fecal loading—they are instrumental in excluding strictures or obstructive lesions. Contrast enema studies may demonstrate a characteristic pouch-like dilatation of the rectum without the typical reversal of the rectosigmoid ratio seen in HD. However, in our cases, this imaging was not feasible due to acute abdominal distension necessitating emergency intervention.

Preston et al. have proposed a diagnostic criterion based on imaging, defining megarectum as a transverse rectal diameter exceeding 6.5 cm at the level of the pelvic brim [6]. Notably, persistent dilatation of the rectum was observed in both patients, even after formation of a defunctionalized proximal colostomy. Postoperative barium enemas demonstrated continued ectasia of the distal bowel, suggesting an intrinsic abnormality rather than a functional adaptation. This persistence distinguishes the condition from ultra-short segment HD, which typically features a narrowed distal rectum below peritoneal reflection. Anorectal manometric and electrophysiological assessments, as performed by Gattuso et al., have not yielded definitive diagnostic markers in such cases [5].

Surgical exploration typically reveals a progressive, pouch-like dilatation of the rectum extending beyond the peritoneal reflection—findings not characteristic of classical HD. Features associated with other congenital anomalies, such as a colovesical fistula (typical in pouch colon syndrome), are notably absent. In rectal ectasia, the dilated bowel is the pathological segment, while in HD, the narrow segment of bowel is the pathological part.

Histopathological examination of the ectatic rectal segment reveals preserved ganglion cells within a hypertrophied smooth muscle layer and intact myenteric plexus architecture, thereby ruling out aganglionosis. These findings are crucial for distinguishing rectal ectasia from HD and other enteric neuropathies (Table 2).

Histopathological comparison between the involved bowel segment of various causes for constipation.

| Sr. no. . | Histological parameters . | Primary rectal ectasia . | Secondary rectal ectasia . | Hirschprung's disease . | Congenital pouch colon . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ganglion cells | + | + | − | + |

| 2 | Nerve bundle hypertrophy | − | − | +/− | − |

| 3 | Smooth muscle hyperplasia and hypertrophy | − | + | +/− | +/− |

| 4 | Nitrinergic neurons | +/− | +/− | − | + |

| Sr. no. . | Histological parameters . | Primary rectal ectasia . | Secondary rectal ectasia . | Hirschprung's disease . | Congenital pouch colon . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ganglion cells | + | + | − | + |

| 2 | Nerve bundle hypertrophy | − | − | +/− | − |

| 3 | Smooth muscle hyperplasia and hypertrophy | − | + | +/− | +/− |

| 4 | Nitrinergic neurons | +/− | +/− | − | + |

Histopathological comparison between the involved bowel segment of various causes for constipation.

| Sr. no. . | Histological parameters . | Primary rectal ectasia . | Secondary rectal ectasia . | Hirschprung's disease . | Congenital pouch colon . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ganglion cells | + | + | − | + |

| 2 | Nerve bundle hypertrophy | − | − | +/− | − |

| 3 | Smooth muscle hyperplasia and hypertrophy | − | + | +/− | +/− |

| 4 | Nitrinergic neurons | +/− | +/− | − | + |

| Sr. no. . | Histological parameters . | Primary rectal ectasia . | Secondary rectal ectasia . | Hirschprung's disease . | Congenital pouch colon . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ganglion cells | + | + | − | + |

| 2 | Nerve bundle hypertrophy | − | − | +/− | − |

| 3 | Smooth muscle hyperplasia and hypertrophy | − | + | +/− | +/− |

| 4 | Nitrinergic neurons | +/− | +/− | − | + |

Initial medical management with oral laxatives may be sufficient in mild cases. However, in severe presentations, especially those unresponsive to conservative therapy, surgical intervention becomes imperative. In emergent scenarios with significant colonic dilatation, a proximal diversion colostomy is often required to alleviate obstruction, prior to definitive reconstruction. Due to the presence of a severely dilated and feces-laden rectum, single-stage pull-through procedures are generally considered unsafe, primarily due to risks of contamination and suboptimal visualization.

In cases where rectal ectasia is associated with ARM, resection or tapering of the dilated segment is essential to prevent persistent postoperative constipation [7, 8]. The surgical management of isolated or primary rectal ectasia without associated ARM remains less clearly defined, and multiple reconstructive approaches have been described i.e. Anterior rectal resection, Duhamel pull-through (DPT), Swenson and Soave procedures [2, 9].

In our first patient, a DPT was initially performed; however, due to persistent symptoms and postoperative imaging showing disproportionate dilatation of the pulled-through colon and residual ectatic segment, a subsequent Swenson’s pull-through with complete resection of the dilated bowel was undertaken.

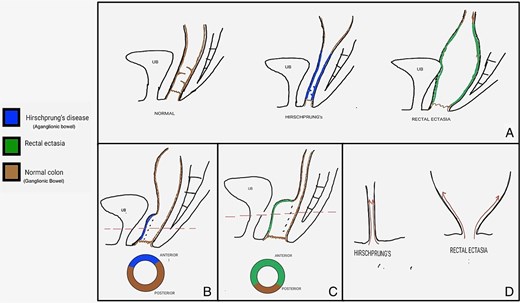

This finding aligns with observations by Gattuso et al., who reported poor functional outcomes when the ectatic rectum was retained in situ [5]. We propose that the significant disparity in luminal diameter between the normal colon (pull-through part) and the retained ectatic rectal reservoir leads to ineffective peristalsis, predisposing to fecal stasis and symptom recurrence (Fig. 2A and B). The ratio of the diameter of the ectatic rectal reservoir to the pulled-through normal colon renders it impossible for the normal colon to generate sufficient peristaltic intensity in the rectal reservoir, leading to symptom recurrence (Fig. 2A and C).

Shows a schematic diagram of various pathologies before and after the surgical procedure. (A) Compares the gross anatomy of a normal colon with that of HD and rectal ectasia. (B) and (C) Show a post-Duhamel pull-through cross-section in HD that illustrates the ratio of aganglionic bowel to normal colon and ectatic bowel to normal colon in rectal ectasia, respectively. (D) Provides an image depicting the direction of dissection for the soave pull-through in HD compared to rectal ectasia.

Considering Soave's pull-through (Fig. 2A and D), unlike HD, the dilated and inverted cone-shaped rectum prevents the creation of a lateral dissection plane in the submucosal layer. The remnant muscular cuff would also be too dilated to accommodate the pulled-through colon. For better surgical outcomes, we propose that bowel restoration must involve the resection of the entire dilated segment, which can only be accomplished through Swenson's pull-through.

Conclusion

Primary rectal ectasia should be kept in the differential diagnosis as a cause of constipation in older children. The surgical intervention should be considered after adequate medical management has failed. We advocate for a complete resection of the ectatic rectal segment to optimize postoperative outcomes. Due to its peculiar anatomy, the Swenson pull-through provides superior outcomes to the Duhamel or Soave's procedure for bowel restoration.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.