-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Tiana Tambyrajah, Jason Diab, Sailakshmi Krishnan, Tariq Cachalia, Dominic Rao, Francis Chu, Recurrent choledocholithiasis following multiple failed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatographies: a case for laparoscopic choledochoduodenostomy, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 9, September 2025, rjaf717, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf717

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Choledocholithiasis is often managed with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) as the gold standard, with indications for surgical intervention being few. In the case of failed ERCP, multiple ERCP procedures or where ERCP is not feasible such as after gastric bypass surgery, choledochoduodenostomy may be considered as an effective intervention. This report discusses a case of an 85-year-old woman who presented with recurrent choledocholithiasis and cholangitis, following multiple failed ERCP procedures. She underwent a laparoscopic choledochoduodenostomy. In the post-operative course, she developed Escherichia coli bacteremia, two peri-splenic collections, and a small bowel obstruction which were all successfully managed. She was discharged after 29 days. Laparoscopic surgical management of recurrent choledocholithiasis is a safe alternative to ERCP. It should be considered in individuals with risk factors for recurrent choledocholithiasis, including elderly patients. Clinical vigilance and a multidisciplinary approach in the elderly are vital for optimal management.

Introduction

Common bile duct (CBD) stones, or choledocholithiasis, affect up to 15% of patients under 60 years and up to 60% of elderly patients [1]. Concomitant choledocholithiasis occurs in 5%–20% of cholelithiasis patients [2]. Presentations vary from asymptomatic to acute cholangitis or pancreatitis. Traditionally, surgical management including choledochoduodenostomy was used. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with sphincterotomy is now the gold standard [3]. Recurrent stones post-ERCP occur in 12.6% of cases, with risk factors including female sex, age > 65 years, CBD diameter > 15 mm, and large and multiple stones on first-episode [4]. In cases of failed ERCP, hepatobiliary flow can be recreated surgically through choledochoduodenostomy. This case discusses laparoscopic choledochoduodenostomy for recurrent choledocholithiasis in an elderly patient.

Case report

An 85-year-old lady of Chinese background presented to the Emergency Department with a 1-day history of generalized abdominal pain and fevers associated with dark urine, anorexia, and lethargy. Her past medical history included open cholecystectomy, hysterectomy, thyroidectomy, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and carotid stenosis. Regular medications included aspirin, atorvastatin, bisoprolol, levothyroxine, pantoprazole, sitagliptin-metformin, telmisartan-amlodipine, and ursodeoxycholic acid. At baseline, she required a mobility aid and cleaning services.

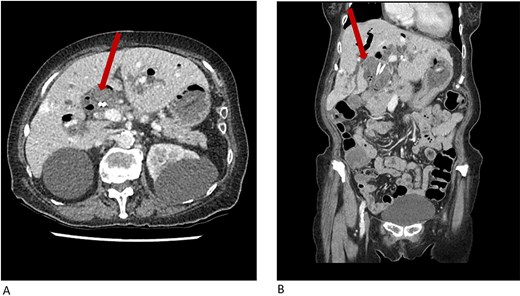

On examination, she was febrile (38.6°C) with otherwise normal vital signs. She had epigastric tenderness with guarding, was Murphy’s negative and non-icteric. Biochemistry revealed mildly deranged liver function and inflammatory markers: bilirubin 15 μmol/l, alkaline phosphatase 69 U/l, gamma-glutamyl transferase 18 U/l, alanine aminotransferase 65 U/l, aspartate aminotransferase 97 U/l, white cell count (WCC) 7.2 × 109U/l, and C-reactive protein (CRP) 71 mg/l. Computer tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis showed CBD dilatation (30 mm) with peripheral enhancement and duodenal reflux (Fig. 1). An incidental hepatic haemangioma was also noted. Her presentation was consistent with cholangitis.

CT abdomen and pelvis showing common bile duct dilatation (arrow) with biliary stents in situ and incidental hepatic hemangioma in (A) axial plane and (B) coronal plane.

Over the preceding 3 years, she had 12 episodes of recurrent choledocholithiasis with acute cholangitis (including extended-spectrum beta-lactamase [ESBL] growths) and had undergone 13 ERCP procedures (including a sphincterotomy and double pigtail stent insertion) in total. The upper gastrointestinal surgical team was consulted for management on this occasion, and the patient and her family consented to an elective choledochoduodenostomy. She was managed with IV meropenem (covering previous ESBL growths), with stepdown to oral ciprofloxacin for 2 weeks until the elective procedure.

The elective laparoscopic choledochoduodenostomy was performed using standard laparoscopic ports. A longitudinal choledochotomy was performed and dozens of stones were collected via endocatch. One existing pigtail plastic stent was removed, while the other remained in situ. A longitudinal duodenotomy was completed and a side-to-side anastomosis was formed using a single-layer absorbable Vloc suture. Remaining stones were washed out of the peritoneal cavity and a Blake drain was placed next to the anastomosis. Post-operatively, she was admitted to intensive care for monitoring.

On Day 2 post-operatively, the patient developed Escherichia coli bacteremia and was commenced on IV meropenem. Three days later, she reported new lower abdominal tenderness and had raised inflammatory markers (CRP 130 mg/l, WCC 7 × 109/l). CT abdomen and pelvis showed a perisplenic collection (95 × 48 × 33.5 mm) and small bowel obstruction. The collection was drained via interventional radiology, although a second subphrenic collection formed, requiring further drainage. Drain specimens grew ESBL Escherichia coli, enterococci and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and vancomycin was added for 2 weeks. The bowel obstruction resolved with therapeutic Gastrografin. Twelve days post-operatively, the surgical drain was removed after confirming no bile leak. Markers of malnutrition were also monitored (peri-operatively: BMI 20.2, albumin 27 g/l, Mg 0.69 mmol/l, corrected Ca 2.05 mmol/l). Geriatric and allied health teams were involved in her care. She was discharged on IV piperacillin-tazobactam and tigecycline for 2 weeks. Her total length of stay was 29 days.

Discussion

This case demonstrates surgical management as a safe alternative to ERCP for recurrent choledocholithiasis in an elderly woman. Risk factors included sex, age, large (≥10 mm) and multiple initial stones, and CBD dilatation (30 mm) post-stenting.

For recurrent choledocholithiasis, ERCP ± sphincterotomy is recommended [5]. Currently, no guidelines regarding surgical management of recurrent choledocholithiasis exist. Literature on thresholds for surgical intervention, such as stone burden or number of prior ERCPs, is limited. While the risk of CBD stone recurrence, post-ERCP is moderately low (12.6%) [4], ERCP with sphincterotomy is associated with duodenobiliary reflux and increased nidus formation, often requiring repeated procedures and anesthesia. Other complications include failed duct cannulation, pancreatitis, perforation, and hemorrhage. Surgical approaches, including choledochoduodenostomy, hepaticojejunostomy, and choledochojejunostomy, provide more definitive solutions, reducing the need for frequent anesthesia. For our patient, surgical management was not previously considered due to age, comorbidities, recurrent cholangitis (ERCP being first-line treatment), technical complexity following previous surgeries, and risk of an open procedure.

Choledochoduodenostomy was first performed in 1888 using a side-to-side anastomosis to facilitate biliary tree drainage and prevent recurrent calculi. A CBD diameter ≥15 mm is recommended for a successful anastomosis [6]; our case measured 30 mm. Common post-operative complications include wound infection, bile leakage, cholangitis, and less commonly, intra-abdominal abscesses, collections, and sump syndrome. The peri-splenic collections in our case were likely secondary to intraoperative bile spillage.

Compared to ERCP, surgical CBD exploration has similar or lower rates of recurrence, complications, and mortality. In patients with previous biliary surgeries [7], laparoscopic CBD exploration offers shorter operative time, reduced hospital stay, and significantly lower complication rates, including post-operative bile leak, compared to an open approach. Systematic reviews demonstrate an average length of stay of 6 days [6] with laparoscopic approaches being significantly shorter [8].

Biliary flow can be reconstructed with side-to-side or end-to-side anastomoses, with similar outcomes [9]. Our case used a single layer of barbed Vloc for the side-to-side anastomosis, which is considered safe, efficient, and adherent [10]. Sump syndrome, albeit rare, can occur with side-to-side anastomoses, when the “sump,” or poorly drained reservoir distal to the anastomosis, accumulates with debris. Management involves improving biliary drainage at the distal CBD often via endoscopic sphincterotomy and duct clearance, or closure of the choledochoduodenostomy [11]. Other complications include cholangitis and reflux. Choledochoduodenostomy may be comparable to hepaticojejunostomy and choledochojejunostomy [6, 12].

Laparoscopic CBD exploration is safe in both elderly (>65 years) and young patients, with no significant difference in stone clearance or mortality [13]. Length of stay is longer in the elderly [14]. Our patient’s prolonged admission was not unexpected given her age, comorbidities, and frailty, the latter reflected by her baseline function and perioperative nutritional status [15]. Literature and our experience favor a laparoscopic approach as a safe option in elderly patients, alongside comorbidity optimization and multidisciplinary care.

Conclusion

In elderly individuals with recurrent CBD stones and subsequent cholangitis, laparoscopic choledochoduodenostomy is a safe alternative to ERCP. Surgical input should be sought early, and the aforementioned procedure should be advocated first in skilled hands. Post-operative complications should be closely monitored for, and a multidisciplinary approach focusing on infection control and functional optimization is needed, particularly in elderly patients.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our acknowledgment to the upper gastrointestinal surgical team members with collection of the data.

Author contributions

The authors contributed to the conception and design of the manuscript, revised it critically for important intellectual content, approved the final version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Conflict of interest statement

No authors have any competing interests. There is no source of financial or other support and no financial or professional relationships which may pose a competing interest.

Funding

None declared.

Data availability

The data is deemed confidential and under ethics cannot be disseminated openly due to confidentiality and privacy.

Consent

Patient consent has been obtained.