-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Liman Zhang, Jie Yang, Qiang Wang, Lili Wang, Tianpeng Zhang, Local excision of perianal skin for pruritus ani: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 8, August 2025, rjaf664, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf664

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Pruritus ani is a neurofunctional dermatological condition frequently encountered in proctology, characterized by persistent perianal itching that can significantly compromise the patient’s quality of life. This case report details a 48-year-old male patient with a 4-year history of perianal itching. Following local excision of the perianal skin, the wound healed satisfactorily on postoperative day 32 and achieved complete resolution of itching symptoms, with the patient attaining full recovery by day 40, thereby demonstrating remarkable clinical efficacy. Additionally, this report reviews relevant literature to investigate the diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for pruritus ani.

Introduction

Pruritus ani is a neurofunctional dermatological condition frequently encountered in proctology. Epidemiological data indicate that in developed countries, pruritus ani has an incidence of ~5% [1], with a male predominance. Its primary clinical manifestation is persistent perianal itching. Initially, patients commonly experience paroxysmal perianal itching without significant skin changes. If left untreated for an extended period, the condition can progress to severe itching, particularly at night. Chronic scratching may subsequently result in skin ulceration, exudation, crusting, thickening, and lichenification [2]. Owing to the condition’s chronic and recurrent nature, some patients may also develop neurasthenia, anxiety, and insomnia [3]. Currently, the treatment of pruritus ani primarily involves maintaining perianal hygiene, using topical washes or ointments, and local block therapy. This case report describes the use of perianal skin local excision for treating pruritus ani, thereby demonstrating the clinical effectiveness of this surgical approach.

Case report

The patient was a 48-year-old male admitted with a chief complaint of ‘perianal itching and discomfort for 4 years’. He had no history of hypertension, diabetes, or other systemic diseases, nor had he undergone any previous perianal surgery. Additionally, he reported no drug or food allergies. Physical examination of the perianal region revealed lichenified and hyperkeratotic skin in the anal folds, accompanied by dry scratch marks, blood crusts, and multiple small fissures (Fig. 1). However, there were no anal fissures, fistulas, or other significant findings. His vital signs were within normal limits: temperature 36.4°C, pulse 72 beats/min, respiratory rate 18 breaths/min, and blood pressure 135/75 mmHg. Laboratory tests, including complete blood count, liver function, renal function, coagulation profile, infectious disease screening, and electrocardiogram, all yielded unremarkable results. Based on these findings, he was diagnosed with pruritus ani.

Preoperative perianal appearance showing lichenified and hyperkeratotic skin in the anal folds with associated scratch marks, blood crusts, and small fissures.

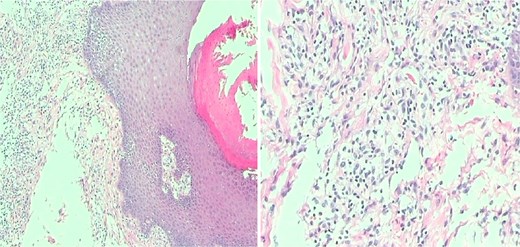

After thorough preoperative evaluation to exclude surgical and anaesthetic contraindications, the patient underwent local excision of perianal skin. During the procedure, hyperplastic, rough, and lichenified areas of perianal skin were meticulously resected. The incisions were designed in a tree-leaf pattern, with intervals of healthy skin tissue preserved between adjacent incisions to facilitate wound healing. Pathological examination of the resected tissue confirmed the presence of chronic dermatitis (Fig. 2). In the postoperative period, the wound was cleaned and dressed daily. By postoperative day 32, the wound had healed completely, with resolution of skin thickening and roughness, and complete alleviation of itching symptoms (Fig. 3). By day 40, the scars had faded significantly, and the patient had achieved full recovery (Fig. 4).

Intraoperative pathological examination of resected lesions demonstrating chronic skin inflammation.

Discussion

Pruritus ani is primarily classified into two categories: primary and secondary [4]. Primary pruritus ani, also referred to as simple pruritus ani, is characterized by perianal itching in the absence

Postoperative wound healing progression and skin changes. Numbers in the lower-right corner indicate postoperative days.

of identifiable pathological factors. It is typically triggered by faecal irritation or chronic scratching, leading to local skin lesions. This form is the most commonly encountered in clinical practice. Secondary pruritus ani often arises from underlying pathological conditions such as infections, systemic diseases, contact dermatitis, anorectal disorders, and drug reactions. It presents with specific skin lesions, with itching serving as a symptom of the underlying condition. Notable examples include pruritus ani secondary to anal fistula, perianal eczema, condyloma, neurodermatitis, and enterobiasis [3]. The pathogenesis of itching involves complex neurophysiological mechanisms. Free nerve endings in the epidermis and superficial dermis function as itch receptors. When perianal skin is exposed to irritants such as dietary factors, faeces, chemicals, or physical agents, various chemical mediators like histamine, kinins, and proteinases are released [5]. These mediators activate the perianal nerve endings, generating neural impulses that transmit the sensation of itching to the central nervous system.

In the treatment of pruritus ani, secondary pruritus ani is largely curable once the underlying cause is addressed. Primary pruritus ani treatment focuses on supportive and local symptomatic relief. Conservative treatments mainly involve oral or topical anti-inflammatory and anti-allergic medications [6]. Common oral medications include antihistamines like loratadine, cetirizine, and fluoropiperox. Topical medications include washes, ointments, and lotions like compound dexamethasone acetate lotion and hydrocortisone ointment. However, many of these topical drugs contain hormones or antifungal agents, which do not align with the aetiology of primary pruritus ani. Consequently, long-term use can lead to drug resistance and dependence, and improper long-term use of topical corticosteroids may cause skin atrophy [7]. Additionally, central nervous system sedatives do not truly cure pruritus ani.

Local block therapy at the site of pruritus ani is also a commonly used treatment. It typically involves injecting a methylene blue solution into the subcutaneous or intradermal tissue. Methylene blue exhibits a strong affinity for neural tissue. Upon local injection, it acts on the nerve endings, reversibly damages the nerve myelin, and disrupts the afferent nerves to achieve an anti-pruritic effect [8], thereby effectively reducing local scratching and promoting the healing of skin lesions and ulcers. Neural remyelination can regenerate within 3 weeks to repair the affected neural tissue. However, in some patients, although pruritus symptoms may improve after methylene blue injection, they cannot be completely eliminated. For instance, a case report documented that a patient’s symptoms improved following the initial injection, but pruritus persisted and required a repeat injection 3 months later for complete relief [9]. Furthermore, a study involving 225 patients indicated that despite the high overall efficacy rate of methylene blue injection, some patients needed a second injection to achieve satisfactory results [10].

Surgery is considered a viable option for patients with chronic, intractable pruritus ani who have shown poor response to conservative treatments or experienced recurrent episodes. By excising the affected skin tissues that are rough, thickened, or lichenified, surgery directly eliminates the source of itching, thereby providing rapid and effective symptom relief and reducing the likelihood of recurrence. In the present case, rather than employing circular resection, the surgical approach involved intermittent, tree-leaf-shaped incisions. This method left some skin tissue between the incisions to prevent scar stenosis. Despite residual hyperplasia, roughness, or scratch marks in the retained skin, these lesions gradually normalized postoperatively. This normalization may be attributed to the following factors: (i) Reduced neurogenic stimulation: With fewer itch-related nerve endings in the resected area and diminished neural impulses in the preserved regions [11]. (ii) Improved inflammatory microenvironment: Removal of the main lesions lowered pro-inflammatory cytokines and alleviated chronic inflammation. (iii) Restored skin barrier function: Postoperative application of moisturizers to the wound promotes recovery by replenishing moisture and lipids, thereby repairing the skin barrier, similar to observations in atopic dermatitis treatment [12]. (iv) Re-established blood supply: Skin bridges preserved local circulation and aided tissue repair.

Given that surgery is more traumatic than conservative treatments, it carries postoperative risks such as infection or poor wound healing. Therefore, surgery should be chosen cautiously. For secondary pruritus ani, skin resection alone may not be effective if the underlying cause is not identified and treated. Additionally, factors such as faecal irritation, clothing friction, excessive cleaning, and diet (e.g. coffee, beer, chocolate) significantly impact the condition [5]. Therefore, patient education to avoid these triggers is essential during treatment.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

Data availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.