-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ahmad Nouri, Islam Rajab, Qutayba Z Ayaseh, Abdallah Hussein, Alisa Farokhian, Yana Cavanagh, Unmasking systemic mastocytosis: a case of gastrointestinal involvement misdiagnosed as achalasia, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 8, August 2025, rjaf590, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf590

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Systemic mastocytosis (SM) is a rare myeloproliferative neoplasm characterized by the clonal proliferation of mast cells in various organs, including the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. GI manifestations of SM, often non-specific, can lead to misdiagnosis, with symptoms overlapping those of common disorders such as achalasia, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, and inflammatory bowel disease. This case report details the diagnosis and management of an 83-year-old female with progressive dysphagia and weight loss, initially suspected to have achalasia. Following further investigation, SM was diagnosed based on histopathologic findings, including mast cell infiltration and CD117 and tryptase positivity, as well as molecular confirmation of the KIT D816V mutation. The case emphasizes the importance of a multidisciplinary diagnostic approach combining endoscopy, histopathology, and molecular testing to distinguish SM from other GI disorders. Early recognition, along with tailored treatment strategies, is essential for improving patient outcomes in SM with GI involvement.

Introduction

Systemic mastocytosis (SM) is a rare myeloproliferative neoplasm characterized by the pathological proliferation and accumulation of mast cells in extracutaneous organs, including the bone marrow, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, liver, spleen, and lymphatic system. The clinical presentation varies, with potential for significant morbidity [1]. The disease encompasses a spectrum of subtypes ranging from indolent to aggressive forms, as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) classification [2, 3].

GI involvement occurs in 14%–80% of patients with SM and may be the initial or predominant manifestation in some cases [1, 4, 5]. Symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and dysphagia result from both local tissue infiltration by mast cells and the systemic effects of bioactive mediators like histamine, prostaglandins, and leukotrienes [3, 6].

Esophageal involvement in SM is uncommon but clinically significant, as mast cell infiltration and mediator release can disrupt esophageal motility and mimic primary motility disorders such as achalasia [7].

Accurate diagnosis of SM requires integration of histopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular data. GI biopsy specimens are essential for diagnosis, especially in patients lacking cutaneous signs of mastocytosis [5, 8].

We present the case of an elderly woman with progressive dysphagia initially diagnosed as achalasia. Subsequent histologic and molecular analysis revealed GI involvement by SM. This case underscores the importance of maintaining a broad differential diagnosis for esophageal dysmotility and the diagnostic value of mucosal biopsies in uncovering rare underlying systemic diseases.

Case presentation

An 83-year-old female with a history of hypertension presented with progressive dysphagia for solids and liquids, accompanied by a 10-pound weight loss over 2 months. She reported undergoing esophageal surgery approximately three decades ago, accompanied by persistent dysphagia that had remained largely unchanged over the intervening years, although specific details regarding the procedure were unavailable. Over the preceding months, she experienced increasing difficulty swallowing, requiring significant modifications to her diet. She also reported occasional postprandial chest discomfort and regurgitation.

A computed tomography (CT) scan revealed distal esophageal dilatation, which appeared increased compared to a prior CT performed a few years earlier, raising suspicion for achalasia. Additional findings included a small hiatal hernia and mild esophageal wall thickening. Given the patient’s advanced age, significant dysphagia for both solids and liquids, and substantial weight loss, there was clinical urgency to proceed with intervention. Although a contrast swallow or esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) would typically be part of the initial diagnostic approach, these were not performed at the outset due to imaging findings suggestive of achalasia. The patient underwent endoscopic peroral endoscopic myotomy (E-POEM). During the procedure, EGD revealed retained food in the esophagus, which was successfully removed. The esophagus appeared tortuous, and the endoscopic findings were consistent with achalasia. Pre-procedural functional lumen imaging probe (FLIP) measurements showed a distensibility index of approximately 3.5 mm2/mmHg with a minimum diameter of 8 mm, indicating impaired esophagogastric junction compliance. Post-POEM FLIP demonstrated the same distensibility index with a mild increase in diameter to 10.5 mm. The Z-line was regular and located 38 cm from the incisors.

The day following the E-POEM, a post-procedural contrast swallow study was performed to evaluate for structural complications or leakage. The imaging demonstrated bifurcation of contrast superior to the level of the endoscopic clips, which was favored to represent an impression of an esophageal fold rather than contrast entering a false lumen.

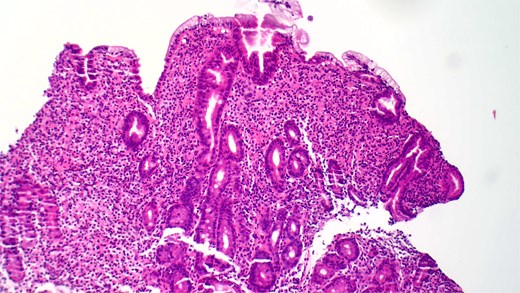

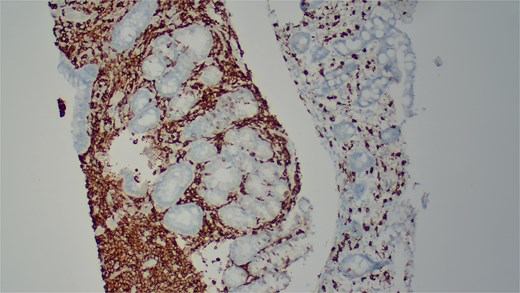

She underwent an EGD, which demonstrated mild chronic duodenitis and erythematous gastric mucosa. Biopsies were obtained from the gastric body, antrum, and duodenum. Histopathological examination revealed abnormal mast cell proliferation in the duodenum (Fig. 1), confirmed by positive staining for CD117 and tryptase, with aberrant CD25 expression (Fig. 2). The gastric mucosa exhibited focal intestinal metaplasia, though no dysplasia was noted. Molecular analysis identified C-KIT D816V mutation. Given these findings, serum tryptase levels were obtained, and additional hematologic evaluation was recommended to assess systemic involvement. The patient was referred to hematology for further assessment of potential bone marrow involvement and systemic treatment options.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining reveals abnormal proliferation of mast cells.

Immunohistochemical staining demonstrates positive expression of CD117.

Discussion

SM represents a rare yet clinically significant myeloproliferative neoplasm, characterized by the clonal proliferation and infiltration of mast cells across multiple organ systems [8]. The disorder is classified according to the 2017 WHO criteria into subtypes that range from indolent SM (ISM) to more aggressive variants such as smoldering SM, aggressive SM (ASM), SM with an associated hematologic neoplasm (SM-AHN), and mast cell leukemia [4].

SM exhibits a broad phenotypic spectrum, with clinical manifestations influenced by both the direct infiltration of mast cells into organ systems and the systemic release of mast cell mediators, including histamine, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and proteases [1, 4, 8]. Common clinical features include cutaneous symptoms such as urticaria pigmentosa and pruritus, systemic symptoms like hypotension and anaphylaxis, and musculoskeletal complaints [1, 8, 9]. GI involvement is frequently reported, with prevalence estimates ranging from 14% to 85%, underscoring the variability in disease expression across different patient populations [1]. Mast cell infiltration of the GI tract into the muscularis propria and myenteric plexus leads to dysmotility mimicking achalasia, in addition to, increased mucosal permeability, and inflammation, leading to symptoms that range from diarrhea and abdominal cramping to peptic ulcer disease and malabsorption syndromes [1, 7, 8, 10]. Organ involvement extends beyond the GI tract, frequently affecting the liver, spleen, and lymphatic system, contributing to hepatosplenomegaly and systemic symptomatology. The delayed diagnosis often seen in patients lacking cutaneous manifestations highlights the necessity of a multidisciplinary approach to evaluation and management [1, 6].

The diagnostic framework necessitates the presence of either one major and one minor criterion or at least three minor criteria [8, 10]. The major criterion is defined by the presence of multifocal dense aggregates of mast cells in extracutaneous tissues, predominantly within the bone marrow, while minor criteria include aberrant mast cell morphology, the presence of c-KIT D816V mutations, aberrant expression of CD25 and/or CD2 on mast cells, and elevated serum tryptase levels [8, 11].

The diagnostic evaluation of SM with GI involvement requires a multifaceted approach that integrates clinical, endoscopic, histopathologic, and molecular data [4]. Endoscopic findings are variable and may include nodularity, mucosal thickening, or ulcerations, but nearly 50% of affected patients present with normal-appearing mucosa, necessitating a high index of suspicion [5, 8]. Histopathologic confirmation relies on the identification of mast cell aggregates within tissue biopsies, along with aberrant expression of CD25 and CD2 [5, 12]. Given that mast cells may be present in increased numbers in other inflammatory conditions, immunohistochemical staining for tryptase and CD117 remains critical for distinguishing SM from other GI disorders [8, 13]. Molecular diagnostics, including KIT D816V mutation analysis, enhance diagnostic accuracy and are positive in over 90% of SM cases [4, 12].

Several conditions mimic the GI manifestations of SM, including achalasia, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, autoimmune atrophic gastritis, and inflammatory bowel disease [4, 7, 8]. Malignancies such as GI lymphoma and metastatic carcinoma must also be excluded, particularly in patients with systemic symptoms and weight loss [6, 14]. The distinction between SM and eosinophilic gastroenteritis is of particular relevance, given their overlapping histologic features; however, SM is uniquely characterized by mast cell aggregates expressing CD25 and the presence of KIT mutations [5, 13].

Pseudoachalasia, a condition mimicking primary achalasia, is commonly caused by malignancies such as esophagogastric junction carcinoma or paraneoplastic processes but can also result from infiltrative diseases, including amyloidosis and SM. The presence of esophageal wall thickening, rapid symptom progression, and older age should prompt suspicion for pseudoachalasia, necessitating biopsy prior to intervention [15].

The therapeutic strategy for SM is contingent upon disease severity and symptomatology, with an emphasis on symptomatic relief and, in advanced cases, targeted molecular therapies [6]. H1 and H2 antihistamines serve as the mainstay for managing mediator-related symptoms, while proton pump inhibitors alleviate acid-related GI manifestations [4, 6]. Cromolyn sodium, a mast cell stabilizer, may offer symptomatic benefit in select patients [4]. Targeted therapies, including midostaurin, a multikinase inhibitor with activity against KIT, have demonstrated efficacy in advanced SM subtypes [4, 14]. Hematologic consultation is essential in cases of SM-AHN, where treatment approaches may necessitate chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation [1, 16].

The prognosis of SM varies significantly by subtype, with ISM typically demonstrating an indolent course, whereas ASM and SM-AHN are associated with high morbidity and reduced survival [4]. The presence of hepatosplenomegaly, bone marrow involvement, and high serum tryptase levels correlates with disease severity and prognosis [8, 9]. Regular monitoring via serum tryptase, endoscopic surveillance, and periodic bone marrow assessment is essential for tracking disease progression [4, 10].

Conclusion

SM with GI involvement represents a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge due to its protean manifestations and potential for misdiagnosis. A high index of suspicion, rigorous histopathologic and molecular assessment, and interdisciplinary management are paramount in ensuring optimal patient outcomes. Advances in targeted therapies and molecular diagnostics continue to refine the treatment landscape, offering improved prognostic potential. Future research should focus on elucidating novel therapeutic targets, refining early diagnostic algorithms, and expanding the understanding of mast cell biology in systemic disease states. Enhanced screening strategies and risk stratification models may further contribute to improving patient outcomes through earlier intervention and personalized therapeutic approaches.

Conflict of interest statement

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethical approval

Our institution does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series.

Informed consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient herself. The participant has consented to the submission of the case report to the journal.

References

Author notes

Ahmad Nouri and Islam Rajab contributed equally to the manuscript

- esophageal achalasia

- mutation

- weight reduction

- deglutition disorders

- inflammatory bowel disease

- eosinophilic gastroenteritis

- endoscopy

- gastrointestinal diseases

- mast cells

- myeloproliferative disease

- proto-oncogene protein c-kit

- signs and symptoms, digestive

- diagnosis

- tryptase

- mastocytosis, systemic

- misdiagnosis

- histopathology tests

- patient-focused outcomes