-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Yehia Nabil, Mena Maged, Menna Sarhan, Mahmoud Magdy, Ahmad Alkheder, Mahmoud M Taha, Non-ossifying fibroma: a case report and comprehensive review of clinical presentation, management strategies, and prognostic outcomes, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 7, July 2025, rjaf468, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf468

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Non-ossifying fibroma (NOF), a benign bone lesion common in children’s long bones, rarely involves the occipital skull. A 4-year-old boy presented with painless occipital swelling. Examination revealed a firm, non-tender mass with no deficits. Imaging showed a well-defined lesion suggesting dermoid cyst. Histopathology confirmed NOF with storiform fibroblasts and osteoclast-like giant cells. Unlike spontaneously resolving long bone NOFs, cranial lesions require excision for diagnosis and cosmesis. Histopathology excludes aggressive pathologies. Advanced imaging and multidisciplinary care optimize outcomes. Long-term monitoring is recommended. Surgical excision achieved cure without recurrence. This case underscores NOF in pediatric skull lesions, advocating tailored care and research.

Introduction

Non-ossifying fibroma (NOF), a benign fibrous cortical defect (FCD) in children [1], has unclear etiology but may involve physeal maturation abnormalities [2]. Described by Sontag et al. (1941) and later termed by Jaffe and Lichtenstein [3, 4], it is classified by WHO as a tumor-like lesion [2]. Diagnosis is challenging due to overlap with aggressive lesions (e.g. aneurysmal bone cysts) [5, 6]. Treatment includes casting or curettage with grafting for persistent cases [7–9]. Epidemiological studies show variability: Japan reported 2.3% NOF and 7% FCD in 6222 children [10], while another study noted 54% male vs. 22% female prevalence [3]. Collier et al. identified bimodal age peaks at 5 years and post-skeletal maturity [11]. Though typically in long bones, rare cases occur in the mandible [12] or occipital bone (as in our 4-year-old male). Histopathological confirmation post-excision remains critical.

Case presentation

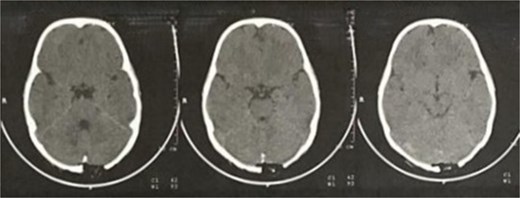

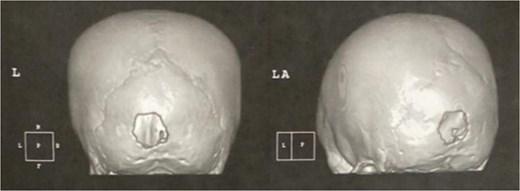

A 4-year-old, otherwise healthy male with no significant past medical history, family history of bone disorders, or prior trauma, presented with a progressively enlarging, painless occipital swelling noticed by his parents over a two-month period. The parents denied any associated symptoms, including fever, headache, vomiting, changes in behavior, or neurological deficits such as visual disturbances or gait abnormalities. There was no history of recent infections or constitutional symptoms. On physical examination, the child was afebrile and hemodynamically stable. A solitary, well-circumscribed, firm, non-mobile, and non-tender mass measuring 1.5 × 1.5 cm was palpated in the midline occipital region. The overlying skin was normal in color and temperature, with no erythema, ulceration, or punctum. No regional lymphadenopathy was detected. Neurological examination, including cranial nerve assessment, motor/sensory function, and reflexes, was unremarkable. Brain computed tomography (CT) with contrast revealed a 14 × 12 mm, well-defined, osteolytic, interosseous lesion in the occipital bone, exhibiting smooth sclerotic margins, cortical thinning, and no periosteal reaction or internal matrix mineralization, the lesion was confined to the diploic space, sparing the inner and outer cortical tables, with no intracranial extension or dural involvement (Figs 1 and 2). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without contrast enhancement, T1-weighted imaging (T1WI) showed an extra-axial space-occupying mass, the mass is iso-intense and well-circumscribed in shape (Fig. 3).

MRI T1WI axial view without contrast enhancement showing an extra-axial space-occupying mass, iso-intense and well-circumscribed in shape.

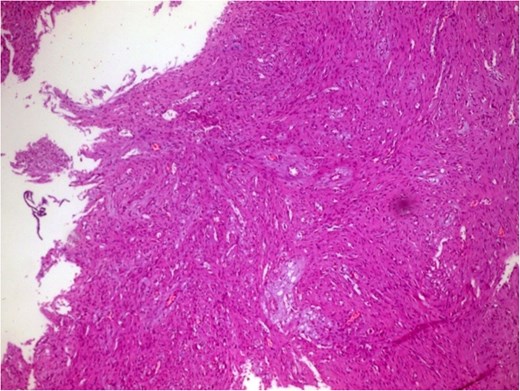

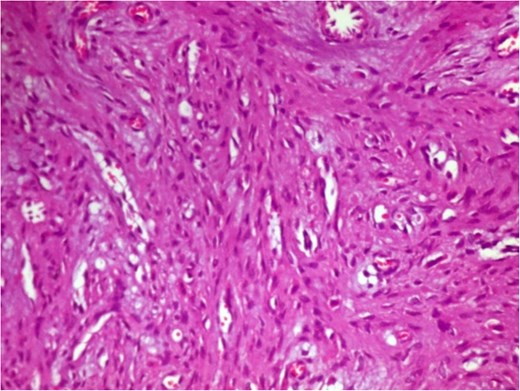

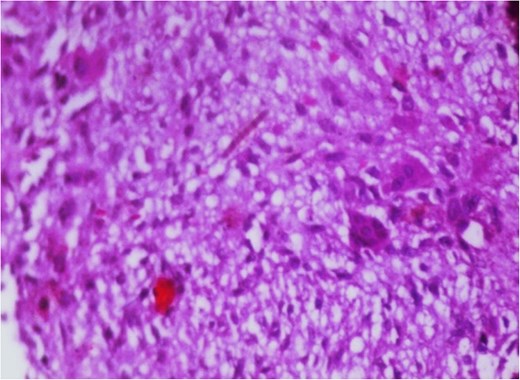

Additionally, magnetic resonance venography (MRV) confirmed a patent superior sagittal sinus with no encroachment of the lesion (Fig. 4). Differential diagnoses included dermoid cyst, eosinophilic granuloma, or benign fibro-osseous lesion. Surgical intervention involved en bloc excision under general anesthesia. A curvilinear incision was made over the mass, followed by subperiosteal dissection, which confirmed the lesion’s confinement to the diploë. Intraoperative frozen section analysis was not performed due to the lesion’s benign radiological features. Histopathological examination confirmed NOF, demonstrating ectodermal inclusion, cellular stroma of spindle-shaped fibroblasts arranged in a prominent storiform pattern, and scattered osteoclast-like giant cells. Notably, no evidence of mitotic figures, nuclear atypia, or necrosis was observed (Figs 5–7). The margins were free of lesional tissue. Postoperatively, the child resumed oral intake within 4 hours and was discharged on postoperative day 2 with analgesics. At the 6-month follow-up, the wound had healed without complications, with no recurrent lesion.

MRV sagittal view showing patent superior sagittal sinus with no encroachment of the lesion.

Photomicrograph in a case of NOF showing interlacing bundles of spindle-shaped fibroblasts in a storiform manner, H&E × 100.

Photomicrograph in a case of NOF showing interlacing bundles of spindle-shaped fibroblasts in a storiform manner, H&E × 400.

Photomicrograph in a case of NOF showing osteoclast-like giant cells, H&E original magnification × 400.

Discussion

NOFs, common benign bone lesions, are developmental anomalies linked to metaphyseal cartilaginous rests or trauma-induced subperiosteal hemorrhage. Affecting ~30% of children [13, 14], they lack genetic/environmental ties. Histologically distinct from FCDs, NOFs are larger, extend into the medullary cavity, and may cause pain or fractures in long bones [2, 13]. Radiographically, long bone NOFs are asymptomatic, eccentric, multiloculated lesions with sclerotic borders and cortical thinning, requiring no biopsy [6, 13]. Cranial involvement, like this occipital case, lacks pathognomonic imaging, complicating preoperative diagnosis. A pediatric occipital NOF, initially misdiagnosed as a dermoid cyst, was completely excised without complications. Histopathology confirmed classic storiform fibroblasts and osteoclast-like giant cells. Recovery was uneventful, with scheduled follow-up for recurrence monitoring. Unlike self-resolving long bone NOFs, cranial lesions demand excision due to cosmetic/compressive risks [8, 14]. Occipital NOFs’ rarity necessitates differentiation from Langerhans cell histiocytosis or osteoblastoma via histopathology. Advanced MRI aids in assessing soft tissue/vascularity. While conservative management suffices for asymptomatic long bone lesions, cranial cases often require surgery. Recurrence rates, <5% in extremities post-curettage, are undefined for skull lesions; 2–3 years of imaging surveillance is advised [4, 10]. Multidisciplinary counseling mitigates family anxiety, particularly for visible lesions. Emerging tools like 3D-printed models and intraoperative frozen sections may refine surgical precision and diagnosis.

The diagnostic complexity of cranial NOF is underscored by its potential to mimic malignant processes on functional imaging. Pagano et al. demonstrated that NOFs in long bones can exhibit significant F18-FDG avidity on PET/CT, erroneously suggesting metastatic involvement in lymphoma patients—a critical interpretive pitfall requiring correlation with anatomical imaging [6]. This metabolic activity, likely reflecting osteoblastic activation during lesion involution, further complicates the assessment of atypical sites like the skull, where benign entities may simulate aggressive pathology. Epidemiologically, our case aligns with the male predominance observed in large cohort studies. Emori et al.’s survey of 6222 Japanese children revealed NOF prevalence of 2.6% in boys versus 2.1% in girls, suggesting biological sex differences in lesion development [10]. Interestingly, their data showed peak NOF incidence at age 14—contrasting with our preschool-aged patient—highlighting that cranial lesions may follow distinct chronological patterns compared to appendicular skeletons. The biological behavior of NOF also warrants consideration. While Herget et al. established that stage B lesions in long bones carry the highest fracture risk (75% transverse diameter involvement in fractured cases) [13], cranial NOFs likely follow different biomechanical principles. The occipital location in our case spared weight-bearing function but posed unique risks due to proximity to dural sinuses, necessitating preoperative MRV assessment to exclude venous compromise. Finally, the epiphyseal involvement documented by Noh et al. [12]—previously considered exceptionally rare—parallels our case’s deviation from classical metaphyseal predilection, suggesting NOFs may exhibit greater anatomical plasticity than historically recognized.

Conclusion

This case highlights the rare occurrence of a NOF in the occipital bone, an atypical site for this benign lesion. While NOFs are well-documented in long bones, their presentation in cranial structures remains exceedingly uncommon, posing diagnostic challenges. In this case, surgical excision was both a definitive diagnostic and therapeutic approach, with histopathological examination confirming the benign nature of the lesion. The patient’s uneventful recovery and absence of recurrence at follow-up further support the efficacy of complete excision in managing symptomatic or atypically located NOFs. Given the rarity of cranial NOFs, further case reports and long-term follow-up studies are needed to better understand their clinical behavior and optimize management strategies.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

We received no funding in any form.

Ethical approval

Ethics clearance was not necessary since the University waives ethics approval for publication of case reports involving no patients’ images, and the case report does not contain any personal information. The ethical approval is obligatory for research that involves human or animal experiments.

Consent of patient

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parents/legal guardians for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Guarantor

The corresponding author.

References

Anderson WJ, Doyle LA.