-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mohanad Ibrahim, Ali Toffaha, Mahwish Khawar, Hamza A Abdul-Hafez, Mohamed Kurer, A rare case of perforated giant mesenteric fibromatosis causing acute peritonitis, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 7, July 2025, rjaf459, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf459

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Desmoid tumors (DT) are rare benign tumors originating from myofibroblasts in the mesentery. Although benign, DTs exhibit local invasion and recurrence and may present sporadically or with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and Gardner’s syndrome. The clinical presentation ranges from asymptomatic abdominal masses to severe complications such as bowel obstruction and perforation. This case report highlights a 46-year-old male with acute diffuse peritonitis due to perforation of a mesenteric fibromatosis (MF). Imaging revealed a large mesenteric mass causing bowel perforation, necessitating an urgent exploratory laparotomy. Surgical intervention entailed resection of the affected small bowel and mesentery with temporary stoma formation. Histopathology confirmed MF with negative margins, and the patient was discharged in stable condition. This case highlights the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in managing such complex cases, the challenges in diagnosing and treating intra-abdominal DTs, and the role of surgical resection with careful postoperative monitoring despite recurrence concerns.

Introduction

Desmoid tumor (DT), or mesenteric fibromatosis (MF), is a condition characterized by the proliferation of myofibroblasts in the mesentery [1]. It accounts for 8% of all DTs, which comprise 0.03% of all neoplasms. It is histologically benign; however, it may invade locally and recur following excision. It can occur sporadically or in conjunction with the Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) mutation and as a component of Gardner’s syndrome [2]. The morphologic heterogeneity and variable clinical presentation, as well as the low incidence of DT (estimated at 3–5 cases per million person-years), make the diagnosis of the disease a difficult task [3]. The presenting features of MF can vary from being an asymptomatic abdominal mass to having abdominal discomfort or pain, bowel or ureteral obstruction, intestinal perforation, fistula, and functional impairment of ileoanal anastomosis following colectomy in FAP [2]. In this case, we examine a case of intra-abdominal DT that was complicated by acute diffuse peritonitis due to mass perforation. This is one of the rare cases to be reported that shows the management of large MF presenting with acute abdomen.

Case presentation

This is a 46-year-old gentleman with no past medical or surgical history who presented to the emergency department with a 3-week history of episodic abdominal pain that increased in intensity 2 days before admission. The pain was associated with constipation and complete obstipation. He also reported a 5 kg unintentional weight loss over a period of 2 months. He denied any bleeding per rectum or melena, and there was no family history of cancer.

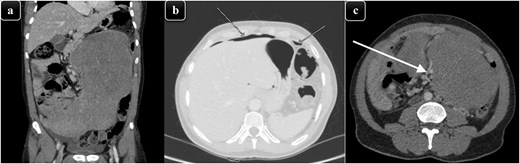

On examination, he looked ill and in pain, was tachycardic with a pulse of 110 bpm, and had a blood pressure of 100/60 mmHg. His abdomen was distended and severely tender with signs of peritonitis, and a huge palpable mass was noted in the entire lower abdomen extending up to the umbilical region. Laboratory tests showed a white cell count of 6.4 (103/μl), C-Reactive protein of 7 mg/l, and lactate of 3.9 mmol/l. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a large neoplastic mass centered in the abdomen with possible bowel invasion resulting in perforation and pneumoperitoneum, and it was encasing the mesenteric vessels in the lower abdomen (Fig. 1). The radiological differential diagnoses included lymphoma, sarcoma, desmoid, and/or gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST).

(a) A coronal view of CT abdomen showing large soft tissue density, homogenously enhancing mass predominantly occupying the left side of the abdomen and reaching to the midline approximately measuring 31 × 19 × 11.7 cm. (b) CT abdomen with an axial view, showing significant pneumoperitoneum. (c) CT abdomen with an axial view showing the mass encasing the mesenteric vessels (white arrow) in the lower abdomen with marked compression and displacement of the adjacent abdominal structures.

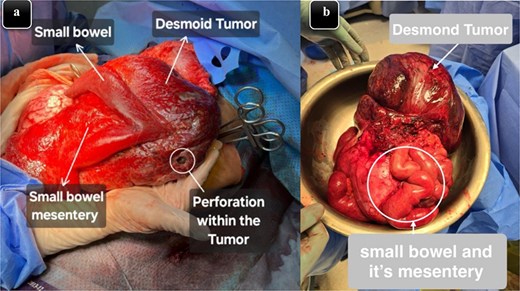

The patient was resuscitated and taken to the operating theater for an exploratory laparotomy via a midline incision with a left rooftop extension to accurately determine the mass’s extent and resectability. Upon exploration, purulent fluid was noted in the upper abdomen and left paracolic gutter, as well as a huge small bowel mesenteric mass involving the ileum and its mesentery with a perforation on the left upper side (Fig. 2). This mass was sitting on the descending colon causing proximal dilatation, but the colon itself was intact. Further dissection led to the resection of the involved small bowel and cecum along with its mesentery, leaving 170 cm of small bowel (Fig. 2). The ileocolic artery was ligated due to its anatomical course through the mass. During dissection, a small iatrogenic injury to the infrarenal abdominal aorta and to the proximal jejunum occurred; both injuries were repaired primarily. In addition, the right ureter was transected due to its proximity to the mass and was repaired primarily over a DJ stent. The abdomen was irrigated and left open for a second-look laparotomy involving vascular and urology teams.

(a) An intra-operative image illustrating the mass that originated from the mesentery along with small bowel adhesion and perforation within the tumor. (b) Specimen image showing the excised well-circumscribed lesion with a smooth external surface along with a portion of the small intestine and its mesentery that was involved.

Postoperatively, the patient was transferred to the ICU, and after optimization, a second-look laparotomy revealed a healthy residual bowel. The distal jejunum and ascending colon were brought out as a double barrel stoma, and the abdomen was closed. The patient was monitored for 10 days, gradually advanced to a full diet, and managed for high stoma output with loperamide. Histopathology confirmed MF completely excised with clear margins. Subsequent scopes ruled out FAP, and MRI surveillance was initiated. Following a normal MRI and an uneventful stoma closure, the patient remained clinically well at 9 months with continued MRI surveillance.

Discussion

The term “desmoid” was introduced by Müller in 1838, derived from the Greek word “Desmos,” meaning a band or tendon. DT represents only 0.03% of all neoplasms, malignant or benign, with an estimated incidence of two to four cases per million individuals annually [3]. There is a slightly higher incidence in women than in men [4]. Although DTs are generally benign, with a 5-year survival rate of 92%, they can recur locally after surgical removal [4, 5]. They most often arise from the abdominal wall or limbs in women of reproductive age but can occasionally develop from the mesentery [4, 6]. MF is defined by fibroblastic overgrowth impacting the mesentery, usually developing following surgical history, though sometimes without any apparent cause. Individuals with FAP, as in Gardner’s syndrome, are particularly susceptible; approximately 10% of FAP patients develop DTs, most of which are abdominal, and fibromatoses associated with FAP tend to be more aggressive and recurrent [7].

The clinical behavior of DTs is variable and depends on the tumor’s location, size, and other factors. Church categorized the clinical course of DTs into four main pathways: spontaneous remission (10%), alternating phases of improvement and deterioration (30%), stable clinical condition (50%), and aggressive progression (10%) [8, 9]. These tumors may present as either a symptomless or painful abdominal mass and can obstruct the intestine or ureter, compromise mucosal blood flow, lead to intestinal perforation, fistulas, unexplained fever, or cause problems with the ileoanal anastomosis after colectomy in FAP cases. In our case, the patient exhibited acute peritonitis due to perforation, necessitating an emergent exploratory laparotomy [2, 6].

Imaging is important for diagnosing, surgical planning, and monitoring intra-abdominal DTs. Ultrasound is commonly used initially to minimize radiation exposure, though its diagnostic significance is limited. CT scan is then recommended to better delineate tumor size and nature; on nonenhanced CT, DTs often show increased density compared to muscle, while contrast-enhanced CT displays varying degrees of heterogeneous hyperenhancement [10]. MRI characteristics vary with cellularity and fibrous content: on T1-weighted images, DTs may appear hypointense or isointense relative to muscle, and on T2-weighted images, they are typically hyperintense, with hypointense bands corresponding to dense collagen fibers [11].

Misdiagnosis is common in DT, with approximately 30%–40% of cases incorrectly identified after histologic analysis due to resemblance to other myofibroblastic disorders [12]. When DT involves the stomach or intestinal wall, it mimics primary gastrointestinal neoplasms such as GIST [13], and radiological methods, including MRI, do not allow for clear discrimination. A case report by Albino et al. highlighted a 27-year-old male whose desmoid fibromatosis was initially misdiagnosed as GIST [5]. Thus, immunohistochemistry remains key for accurate diagnosis [14].

Treatment options include wide excision, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and antiestrogen therapy. Recently, initial observation has been recommended unless rapid progression mandates urgent intervention [4, 15]. Abdominal desmoids can be excised in 53% to 67% of cases [16], yet 25%–50% of mesenteric and retroperitoneal DT recur after radical surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy [4]. Intra-abdominal DT resection is associated with high intra- and postoperative morbidity and mortality, including hemorrhagic complications and bowel loss, potentially resulting in short bowel syndrome and fistula formation [17]. In our case, diffuse peritonitis necessitated urgent exploration via a multidisciplinary team approach.

In conclusion, MF typically progresses gradually and asymptomatically, with emergent conditions such as perforation being rare. Surgical resection remains the primary treatment, although it carries significant perioperative risks, emphasizing the need for a multidisciplinary approach.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

References

- abdominal mass

- abdominal pain

- familial adenomatous polyposis

- gardner's syndrome

- alcohol withdrawal delirium

- fibromatosis, abdominal

- fibromatosis, aggressive

- intestinal perforation

- intestine, small

- mesentery

- peritonitis

- stomas

- surgical procedures, operative

- abdomen

- diagnostic imaging

- neoplasms

- peritonitis, acute

- laparotomy, exploratory

- myofibroblasts

- excision

- histopathology tests