-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Andrej Nikolovski, Radomir Gelevski, Ivan Argirov, Cemal Ulusoy, Uncommon degloving intestinal injury accompanied by complete disruption of the rectus muscles in patient with seat belt sign: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 7, July 2025, rjaf445, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf445

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Blunt abdominal trauma rarely causes injury to hollow intraabdominal viscus. Still, in victims with seat belt sign, a high index of suspicion should be raised. Additionally, accompanied injury to the abdominal wall muscles is reported. We present a case of a male patient injured in a high-velocity car accident presented with seat belt sign and peritoneal signs. Laparotomy revealed uncommon degloving injury of the small intestine with additional mesentery lesions and lacerations of the ascending and descending colon. Concomitant transection of both rectus abdominis muscles was also encountered.

Introduction

Intestinal injury resulting from blunt abdominal trauma in high-velocity accidents is uncommon, with an incidence of 1%. One of the mechanisms of injury in victims with fastened seat belts is an aggressive deceleration moment that can lead to intestinal lacerations, perforations, mesentery tearing, and even intestinal transection [1]. Both operative and conservative treatment are described as therapeutic options, depending on certain clinical and radiological parameters [2]. The current case presents injuries to both the small and large intestines due to a high-velocity car accident.

Case presentation

A 25-year-old male patient was injured as a driver in a high-velocity light vehicle incident (slipping off the road at a speed of 120 km/h, followed by the car tumbling). On admission, he was conscious with a main complaint of abdominal pain. Blood pressure was 100/60 mmHg, heart rate of 90/min, and blood oxygen saturation of 93%. Abnormal laboratory values were Leucocyte count of 19.4 × 109/L (3.5–10), neutrophils count of 83 (45–70), serum glucose level of 8.42 mmol/L (3.5–5.5), and C-reactive protein serum value of 8.8 mg/L (<5).

A physical exam presented with seat belt sign injury upon inspection (Fig. 1) and diffuse abdominal tenderness suggestive of an acute abdomen. Since the patient was hemodynamically stable, a computerized tomography (CT) scan was ordered. It excluded trauma to the head and neck but was positive for right-sided partial pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, zones of bilateral pulmonary concussions, and non-dislocated fracture of the left 11th rib. A thoracic surgeon was consulted regarding the thoracic injuries and it was advised to manage the injuries with symptomatic therapy (analgesics, oxygen) and close follow-up. Abdominal CT scan revealed free intraabdominal fluid presence, no solid organ injury, and disrupted continuity of both rectus muscles. Indication for emergency laparotomy was set.

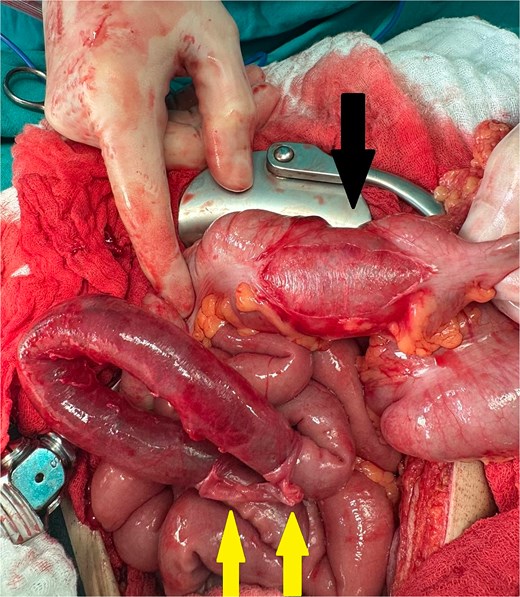

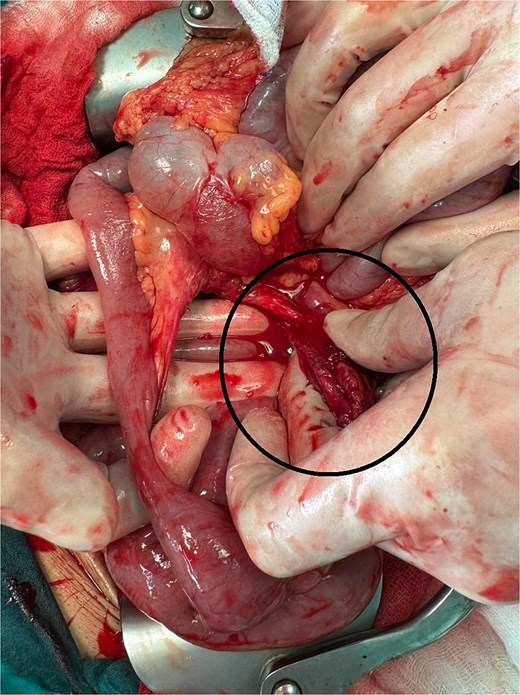

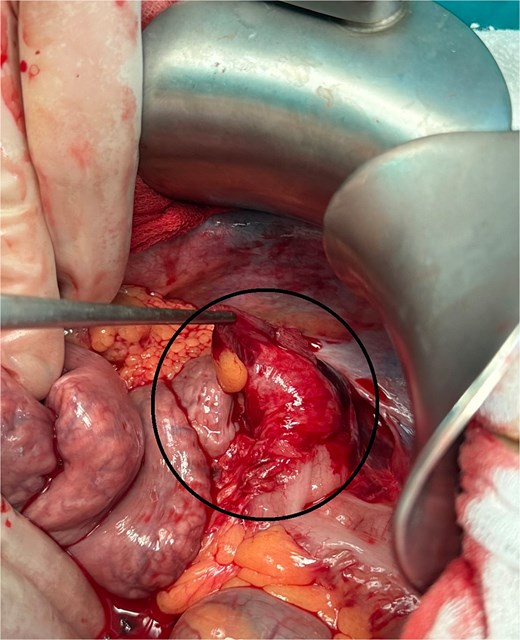

During laparotomy, a rectus abdominis muscle disruption was noted (Fig. 2). Intraoperatively, one liter of free blood was encountered. After its evacuation, exploration revealed zones of intestinal lacerations to the small intestine, the ascending and the descending colon, and injury of the mesentery with active bleeding (Figs 3–6). According to the Organ Injury Scaling (OIS) 2020 update [3], the ascending colon injury (from Fig. 3) was classified as OIS grade II (laceration <50% of circumference without transection) and was treated with seromuscular sutures. The descending colon injury (from Fig. 6) was classified as OIS grade III (laceration >50% of circumference without transection). Finally, both small intestine injuries with long degloving segment (from Figs 3 and 4) and the one with the de-vascularized segment from Fig. 5 were classified as OIS grade V (de-vascularized intestine segment). Respectively, the last three bowel injuries were treated with segmental resection and termino-terminal (one-layered hand-sewn anastomosis) each. Laparotomy closure was done without rectus abdominis muscles repair (only fascial closure was employed). In the postoperative course repetitive chest X-ray exams presented with pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum resolution. The wound presented with surgical site infection (superficial) that was treated with daily dressings in the patient ward. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 10.

Ascending colon laceration <50% (black arrow) and degloving injury to the small intestine (yellow arrows).

Small intestine from Fig. 3 (instruments holding the torn intestinal serosa).

Devascularized intestine with mesentery defect and bleeding point (encircled) manually compressed by the 1st assistant.

Discussion

Solid organs (liver, spleen, and kidney) are most commonly affected in blunt abdominal trauma. Hollow viscus and mesentery lesions are rare and pose diagnostic challenges. High-energy trauma in motor vehicle accidents associated with deceleration moment in victims with fastened seat belt is particularly pointed as a risk factor for intestinal and mesentery injuries [4]. The small intestine is the most common hollow viscus injured followed by the colon, duodenum, stomach, and rectum [5].

The Organ Injury Scaling (OIS) 2020 update [3] comprehends the following grades of intestinal injury (grades are the same for small and large intestine):

Grade I: Contusion or hematoma laceration – partial thickness, no perforation;

Grade II: Laceration <50% of intestinal circumference;

Grade III: Laceration >50% of intestinal circumference without transection;

Grade IV: Transection of the intestine and

Grade V: Laceration-transection of the intestine with segmental tissue loss; vascular-devascularized segment.

The mechanism of injury that leads to intestinal wall disruption and degloving is explained with a deceleration that produces a shearing force. This results in intestinal wall disruption, especially between its fixed and mobile parts. Such a mechanism is likely to explain the injuries to the ascending and the descending colon in this case. On the contrary, small intestine injuries (degloving and mesentery injury) are probably caused by a combination of the deceleration force and the direct damage due to increased intraabdominal pressure between the seat belt and the victim’s spine.

Whenever a patient presents with a visible seat belt sign, a high index of suspicion for hollow viscus injury should be maintained, especially if the CT scan excludes solid organ lesions despite the presence of free fluid in the abdominal cavity. According to Biswas et al. [6], almost 60% of the victims with seat belt signs suffered from small intestine injuries. Besides free fluid, free intraperitoneal air, intramesenteric fluid, and alterations in the gastrointestinal wall and mesentery may be seen on the CT scan if an intestinal injury is present. In such cases, the sensitivity of the CT scan for hollow viscus injury ranges from 83.5% to 99.4% [1, 7]. Intestinal injuries due to blunt abdominal trauma may be missed in up to 20% of patients [8], as seen in this case.

In hemodynamically stable patients with the absence of abdominal tenderness, despite the presence of intraabdominal fluid, non-operative management should be initiated, with hospital admission, close monitoring, and repetitive diagnostics. Any sign of deterioration in hemodynamics and/or the occurrence of peritoneal signs should prompt conversion of treatment to surgery.

Transection of the rectus abdominis muscle following seat belt trauma in combination with intraabdominal organs although rare, was reported previously [8]. Delayed or immediate rectus muscle repair is described to be employed depending on the patient’s condition, comorbidities, and the extent of the damage [9, 10].

Conclusion

Intestinal lesions resulting from blunt abdominal trauma, though uncommon, can occur in patients exhibiting a seat-belt injury sign and may necessitate exploratory laparotomy followed by multiple intestinal resections. Early diagnosis and the decision to proceed with surgery prevent delayed treatment and subsequent abdominal contamination, thereby facilitating intestinal resection with safe primary anastomosis.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

There is no funding to declare.

Data availability

Data is available upon reasonable request.