-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Bruno Matos Santos, Florence Latinis, Michele Podetta, Cosimo Riccardo Scarpa, Is conservative management safe for mesenteric venous ischemia? Two case reports, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 7, July 2025, rjaf318, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf318

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Acute venous mesenteric ischemia (AVMI) caused by porto-mesenteric thrombosis, is a rare yet life-threatening condition with nonspecific symptoms. It necessitates high clinical suspicion for timely diagnosis. Enhanced computed tomography (E-CT) is the gold standard for diagnosis. Unlike arterial mesenteric ischemia, which requires immediate surgical or interventional radiology interventions, AVMI can be managed conservatively with anticoagulation, antibiotics, and bowel rest, although close monitoring is essential. This report presents two cases of AVMI affecting the small bowel, attributed to extensive porto-mesenteric thrombosis and managed non-surgically initially. One patient later required bowel resection following delayed perforation. AVMI is an often underrecognized diagnosis, making early recognition vital for initiating prompt treatment. While radiological assessments may initially raise concerns and suggest small bowel necrosis, conservative management can be employed to prevent intestinal infarction and perforation and the need for surgical intervention. Nonetheless, follow-up is necessary. Unfortunately, late perforation can occur and must be recognized immediately.

Introduction

Acute venous mesenteric ischemia (AVMI) is an infrequent serious condition caused by mesenteric venous thrombosis, leading to progressive small bowel hypoperfusion. Without treatment, it may progress to irreversible necrosis, perforation, and peritonitis [1, 2]. AVMI represents 0.09%–0.2% of emergency abdominal pain cases and 5%–15% of acute mesenteric ischemia cases. Although splanchnic venous thrombosis is uncommon, its detection has increased with imaging [3, 4]. Predisposing factors include portal hypertension, hypercoagulability, inflammatory bowel disease, and recent abdominal surgery (e.g. splenectomy), though significant cases remain idiopathic [4]. This report describes two cases of small bowel ischemia secondary to extensive porto-mesenteric thrombosis, both initially treated conservatively.

Case report

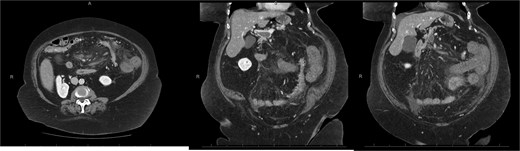

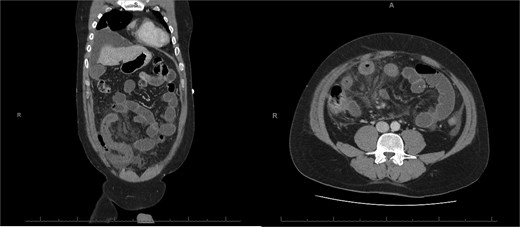

A 76-year-old female with a 3-day history of left upper abdominal pain, vomiting, and haematochezia. Her history included pulmonary embolism, multiple deep vein thromboses, with no ongoing anticoagulation, and an open partial colectomy for complicated diverticulitis a decade earlier. On admission, she was afebrile but tachycardic and showed localized tenderness in the left hypochondrium. Laboratory revealed leucocytosis with a white blood cell count (WBC) of 12 G/L, elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) of 46 mg/L, and hyperlactatemia of 2.6 mmol/l. Enhanced computed tomography (E-CT) revealed jejunal venous ischemia in the left upper quadrant, secondary to extensive porto-mesenteric thrombosis with reduced bowel wall enhancement, distention, and free intraperitoneal fluid (Fig. 1). She was managed conservatively with unfractionated heparin (UFH) with a bolus of 5000 U/l followed by 30 000 U/l/24 h (target INR 0.35–0.7), Piperacillin-Tazobactam, and bowel rest. After 48 h of monitoring in the intensive care unit (ICU), she exhibited marked biological and clinical improvement. E-CT on the third day showed restored bowel wall enhancement and stable porto-mesenteric thrombosis (Fig. 2). She was discharged on therapeutic low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) with enoxaparin sodium 120 mg every 12 h. At the 3-month follow-up, E-CT revealed near-complete thrombus resolution, without intestinal sequelae (Fig. 3).

Abdominal E-CT of the first patient at admission. The white arrows indicate extended porto-mesenteric thrombosis, while the dashed arrows reveal jejunal venous ischemia with a lack of bowel wall enhancement, bowel distension, and free fluid.

Follow-up E-CT 72 h after conservative management in the first patient. Dashed arrows show improved viability of the small bowel with bowel wall enhancement. White arrows revealed the stability of the extended porto-mesenteric thrombosis.

Three-month E-CT of the first patient showing nearly complete thrombosis resolution, with no signs of intestinal distress.

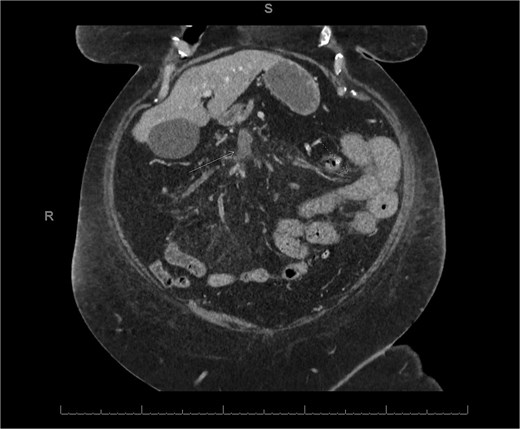

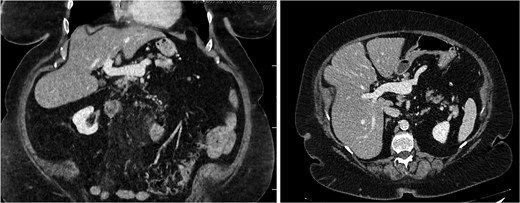

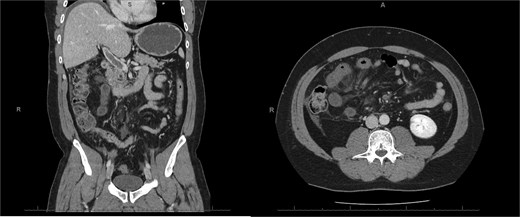

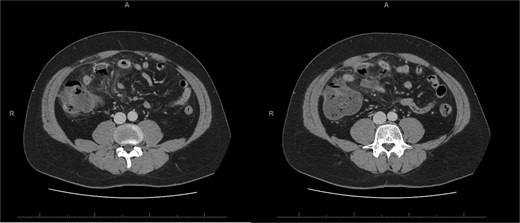

A 45-year-old male presenting with a 10-day history of isolated right lower quadrant (RLQ) abdominal pain. His history included deep vein thrombosis, coronary artery disease with prior STEMI, left anterior descending artery stenting in 2014, and ongoing antiplatelet therapy with aspirin. Upon admission, RLG tenderness was noted. Laboratory revealed leucocytosis (WBC 16 G/L) and elevated CRP (70 mg/L). E-CT revealed superior mesenteric and portal systems thrombosis with ischemia of a small bowel loop in the RLQ, characterized by absent bowel wall enhancement and free fluid (Fig. 4). Besides these findings, he was managed conservatively with a UFH bolus of 5000 U/l, followed by a continuous infusion of 36 000 U/l over 24 h (target INR 0. 35–0. 7), Ceftriaxone and Metronidazole, bowel rest, and ICU monitoring for 48 h. Clinical and biological improvement was rapid. E-CT on the second day showed no signs of perforation (Fig. 5). He was discharged after 7 days on LMWH (enoxaparin sodium 90 mg every 12 h). Twenty days later, he re-presented with acute RLQ pain and localized peritonism. E-CT revealed a covered perforation of the previously ischemic small bowel loop (Fig. 6). A segmental bowel resection with primary anastomosis was performed by laparotomy (Fig. 7). The postoperative course was uneventful, and he was discharged on postoperative day 4 with sodium enoxaparin 90 mg/12 h.

E-CT in the second patient at admission. White arrows showing porto-mesenteric thrombosis. Dashed arrows indicate a portion of small bowel loop ischemia in the right lower quadrant characterized by the absence of bowel wall enhancement and free fluid.

E-CT of the second patient 48 h after conservative management, showing no further complications, including no signs of perforation regarding the bowel wall located with dashed arrows.

E-CT of the second patient, 20 days after the first admission. White arrows show covered perforation concerning the previous ischemic small bowel loop.

Perioperative images of the resected ischemic perforated jejunal segment in our second patient.

Discussion

AVMI is a challenging condition, often misdiagnosed and mismanaged [5]. E-CT is the diagnostic gold standard imaging [5]. Few cases of AVMI have been described in the literature. While current guidelines focus on acute arterial mesenteric ischemia which typically requires urgent surgical or endovascular intervention, conservative management may be appropriate for AVMI [6]. Kumar et al. support this approach in their retrospective study, particularly in large-vessel thrombosis (e.g. portal or splenic vein involvement) with a lower risk of perforation than isolated small mesenteric vein thrombosis often linked to inherited thrombophilia [6]. In our cases, porto-mesenteric thrombosis occurred without evident etiology, suggesting an idiopathic origin. Hematologic workup excluded inherited and acquired thrombophilia (protein C/S deficiency, factor V Leiden, prothrombin gene mutation, antiphospholipid antibodies, and JAK-2 mutation). There were no hematologic signs of neoplasia or myeloproliferative disease.

Both cases involved extensive idiopathic porto-mesenteric thrombosis in atypical locations, leading to small bowel ischemia. Due to the absence of acute abdomen or radiological evidence of bowel perforation at admission, initial conservative management—anticoagulation, antibiotics, and bowel rest—was deemed appropriate. Unfortunately, one patient developed delayed bowel perforation, requiring urgent laparotomy with small bowel resection and primary anastomosis. These cases highlight that while conservative treatment is feasible, vigilant monitoring is crucial. Prompt concern for complications should arise with any clinical changes. The primary goal in managing venous mesenteric ischemia is to prevent thrombus progression and bowel infarction. Current literature supports conservative therapy in select cases, but a high index of suspicion for complications such as perforation must be maintained. Surgical intervention should be guided by clinical and radiological signs of progression to conditions such as bowel wall infarction, perforation, and peritonitis. Anticoagulation is the cornerstone of AVMI management, it prevents thrombus extension, promotes bowel reperfusion, and reduces morbidity and mortality. UFH should be initiated promptly. One study reported 80% of recanalization with anticoagulation within 5 months [7]. UFH is recommended in hospitalized patients, especially with renal impairment or surgical risk. LMWH offers predictable pharmacokinetics but is contraindicated in renal failure [7]. Long-term management involves warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0), while DOACs, though less studied, are supported by some experts [8]. Duration depends on etiology; 3–6 months for reversible causes, lifelong for idiopathic or with thrombophilia. In both presented cases, UFH was initiated during hospitalization due to surgical risk, followed by LMWH for 3 months during hematological workup screening. The first patient, later found to carry a mild JAK2 V617F mutation, was prescribed long-term apixaban (5 mg daily). The second patient, with recurrent idiopathic thrombosis, was discharged on long-term rivaroxaban (20 mg daily).

Conclusion

AVMI is rare but potentially fatal if unrecognized. Early E-CT diagnosis and high clinical suspicion are critical. Conservative treatment may suffice without complications. However, delayed perforation can require surgery. Close monitoring and timely, structured care are essential to optimize its outcomes.

Conflict of interest statement

There are no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise which could influence bias.

Funding

No funding was needed for this case report.