-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Miguel Ángel Moyón, Johan Stephany Añazco, Alex Enrique Vásconez, David Larreategui, María Belén Torres, Natali Moyón, Tatiana Borja, Gabriel Alejandro Molina, Abdominal tuberculosis in a patient with ankylosing spondylitis and infliximab: is the risk still too great? A case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 6, June 2025, rjaf422, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf422

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Ankylosing spondylitis is a chronic inflammatory spondyloarthropathy that will cause severe symptoms and complications if left untreated. Anti-TNF-α inhibitor is the treatment of choice, yet all treatments have difficulties, and opportunistic infections following this therapy are well known. Reactivation of latent tuberculosis (TB) and abdominal TB is a serious problem in this therapy since diagnosis is difficult, as symptoms are nonspecific, and complications can be fatal. We present the case of a 47-year-old female doctor with a past medical history of ankylosing spondylitis; she was treated with infliximab. She began developing abdominal pain that led to an acute abdomen due to abdominal TB. After successful treatment, she fully recovered, and the patient is doing well in follow-ups.

Introduction

Infliximab is an inhibitor of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), which has been used successfully to treat inflammatory diseases [1]. It has various side effects, including immunosuppression, demyelinating diseases, and cardiac effects [1, 2]. One of the most serious complications is the development of latent tuberculosis (TB) [1]. Since TNF-α is essential to fight against Mycobacterium tuberculosis, its inhibition may cause severe complications in endemic areas or latent TB [2]. Therefore, patient selection and surveillance are vital to treat these patients adequately [1–3].

We present the case of a 47-year-old female doctor with a past medical history of ankylosing spondylitis; she was treated with infliximab. Nonetheless, she began developing abdominal pain that led to an acute abdomen. After surgery, abdominal TB was diagnosed and successfully treated. On follow-ups, the patient is doing well.

Case report

The patient is a 47-year-old female doctor with a past medical history of ankylosing spondylitis. She was diagnosed over 3 years ago and since then has been treated with painkillers and corticosteroids. Despite treatment, her disease advanced in the last 2 years, and pain became unbearable at times; therefore, infliximab (5 mg/kg every 6 weeks) was initiated prior to a negative latent TB test with a good response.

Due to her profession, being in a hospital in Ecuador, she has been continuously exposed to several patients with respiratory issues. And 4 months prior, she started to experience night sweats, followed by sudden episodes of acute pain in her lower abdomen. At first, the pain was mild and resolved spontaneously. Therefore, she did not give it the importance it needed and self-medicated, masking many of her symptoms. Nonetheless, after 15 days, the pain worsened until it became unbearable and was accompanied by severe episodes of nausea and vomits; therefore, she was brought immediately to the emergency room.

On clinical evaluation, a tachycardic and febrile patient was encountered. Her abdomen was distended with severe tenderness. The cardiopulmonary examination was unremarkable, and complementary exams were requested. They revealed an 80 mm/h erythrocyte sedimentation rate, a C-reactive protein at 63.6 mg/dl, leukopenia (2.3 × 109/l), and thrombocytosis (498 000/mm3). The remaining exams were normal, including total bilirubin, hematological tests, and renal function.

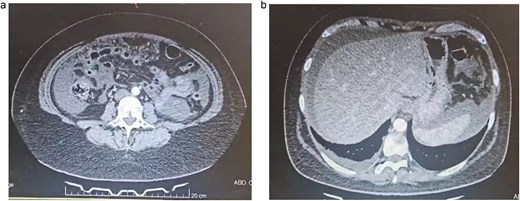

Due to this, a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) was requested to help in the diagnosis. It revealed 1000 cc of free liquid in her abdomen and inflammation of the peritoneum with diffuse peritoneal thickening and right pleural effusion (Fig. 1a and b).

(a) Abdominal CT, multiple bowel loops are seen surrounded by liquid. (b) Abdominal CT, thickening of the peritoneum is seen with free liquid.

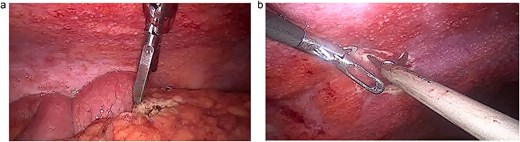

With these findings, the differentials included peritoneal carcinomatosis, pseudomyxoma, peritoneal, and peritoneal lymphoma. Yet none of those could have developed that quickly and with those symptoms. However, abdominal TB due to infliximab was finally considered a diagnosis after a comprehensive diagnostic interdisciplinary assignment, as she was a physician and worked in a TB–endemic area. After researching her history, the medical team became aware of her symptoms and close connection with respiratory patients. Because of this, surgery was planned after consent was obtained. At laparoscopy, 1200 ml of loculated liquid was discovered, and the whole extent of the peritoneum was filled with multiple nodules, some of which created adhesions between the bowel and the omentum. Several biopsies of the omentum and peritoneum were taken, the liquid was drained, and the procedure was completed without complications (Fig. 2a and b).

(a) Laparoscopy, the peritoneum is filled with lesions. (b) Laparoscopy, the intestine and omentum are completely covered in nodules.

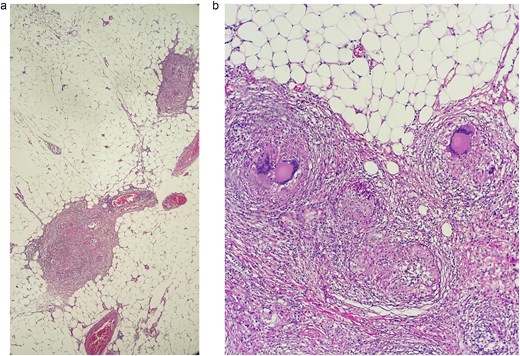

Pathology revealed a lymphocytic-predominant ascitic fluid, with a white cell count of 1100 cells/mm3 and a protein level of 29 g/l; on the biopsy, a thickened peritoneum was seen with dense adhesions and multiple caseating granulomas. A Ziehl-Neelsen stain of the ascitic fluid was also done but was negative, yet the culture for TB was positive (Fig. 3a and b).

(a) Sections processed by hematoxylin and eosin staining. A tuberculous granuloma, multiple lymphocytes, and plasma cells are seen surrounded by a peripheral rim of multinucleate giant cells in the biopsy of the peritoneum. (b) Sections processed by hematoxylin and eosin staining, two granulomas are seen in the biopsy of the omentum.

Abdominal TB reactivation after the use of anti-TNF-α was the final diagnosis.

During her postoperative period, infliximab was discontinued, and a standard 4-drug regimen consisting of isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol was started, and she was discharged 7 days after without complications.

Four months after this event, she has continuously followed up with her rheumatologist, she is on a different treatment and has had no similar events.

Discussion

One of the remarkable achievements of medicine has been the development of anti-TNF-α therapies [1]. TNF-α is a pro-inflammatory and immunomodulatory transmembrane protein expressed by macrophages, CD4+ T cells, mast cells, neutrophils, and NK cells [1, 2]. When activated, TNF-α is cleaved and released, promoting inflammation [2]. Since Kohler and Milstein first developed this therapy in 1975, these antibodies can wield two therapeutic effects: first, by binding to an antigen, they neutralize its biological functions, and second, by opsonizing target cells, they can induce a receptor-mediated immune response [1–3].

There are five FDA-approved anti-TNF-α drugs; one is infliximab, a monoclonal antibody that binds to TNF-α with high affinity, neutralizing its effect [2, 3]. Since its approval in 1999, it has been used for patients with Crohn's disease, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis, among others [2, 3].

Since this antibody has an excellent response rate (up to 81%), it makes ankylosing spondylitis an ideal disease for its use [4]. Treatment of these patients consists of mobility exercises, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, steroids, and anti-TNF-α biological agents [4, 5]. However, these treatments have been regretfully associated with serious adverse effects, such as pneumonia, hepatotoxicity, and reactivation of TB [4, 5].

In our case, since the patient had an inadequate response to standard therapy, anti-TNF-α therapy was initiated with good results. However, abdominal TB emerged. TB is a particular concern in these treatments, since TNF-α plays a key role in the immune system response against M. tuberculosis [6]. TNF-α increases the antibacterial activity of macrophages and causes lymphocyte migration and proliferation by releasing cytokines and chemokines [6, 7]. This contributes to the formation of granulomas and prevents bacilli from reproducing and spreading [1, 6].

About 8 million people fall ill with TB each year, and 1.6 million die from it [6]. In 2020, Sartori et al. found that up to 15%–25% of adults carry a latent TB infection and, therefore, the use of anti-TNF in high-prevalence countries like ours increases the risk of developing TB by 10–20 times [6, 7]. Therefore, latent TB infection must be investigated before initiating therapy to decide whether prophylaxis is needed. Regretfully, this is only partially effective because most patients who develop TB are negative at baseline [1, 6, 7].

If TB appears, the majority of manifestations are pulmonary, 25% of cases are extrapulmonary (abdominal TB is rare), and about one-fifth are disseminated [6, 7]. It should be noted that most TB cases develop within a year and a half of anti-TNF therapy [8, 9].

In our case, the patient had a negative latent TB infection test. However, she was a physician in Ecuador, which predisposed her to TB infection. Although she and her physician were aware of the risk, she ignored several signs and symptoms and did not promptly see her physician, who failed to follow-up with her adequately. This series of errors led to the patient's illness.

With the increasing use of anti-TNF agents, physicians treating inflammatory diseases in regions where TB is endemic must be highly aware of their efficacy and troublesome side effects. TB may not be an issue in developed countries, but it is still a burden we continue to carry in Ecuador. Therefore, we cannot lose sight of its diagnosis and consider that every therapy can have consequences.

Conclusions

There is a definite risk of TB in patients using anti-TNF. Still, proper follow-up and risk assessments are necessary for this and every therapy to minimize risks, prevent complications, and provide appropriate medical care.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.