-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Derar I I Ismerat, Barah K S Alsalameh, Raneen T M Farash, Bayan Qnaibi, Amal Mahfoud, Afnan W M Jobran, A typical presentation of previable HELLP syndrome: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 4, April 2025, rjaf255, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf255

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The rare condition known as HELLP syndrome is typified by hemolysis, low platelet counts, and high liver enzymes. We report a case of a 25-year-old primigravida who presented at a previable gestational age with nonspecific symptoms. She was diagnosed with hepatic infarction, a rare but severe complication of HELLP syndrome, and was managed promptly to prevent maternal morbidity and mortality.

Introduction

HELLP syndrome is a condition that occurs in pregnant and postpartum women and is characterized by hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count [1]. It can be a complication or progression of severe preeclampsia; however, recent evidence suggests distinct causes. Hypertension or proteinuria is absent in at least 15%–20% of patients with HELLP syndrome [1].

HELLP syndrome is diagnosed biologically in the presence of hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia (< 100 000 /ul), and elevation of aminotransferases, whereas the most frequent clinical symptoms are nausea, vomiting, and epigastric, and right upper quadrant pain [2, 3].

Hepatic infarction is not a common complication of HELLP syndrome, but it is very severe and leads to death in 16% of cases [2].

This is a case of a woman who presented at 23 + 5 weeks of gestation with HELLP syndrome, highlighting the occurrence of this condition before the limit of viability. This case report aims to emphasize the need to be vigilant that PET/HELLP syndrome can occur in very early gestation, albeit rarely.

Case report

A 25-year-old woman (G1P0A0) at 23 weeks and 5 days of gestation presented with mild right upper quadrant and epigastric pain, along with decreased fetal movement for 3 days. She had a history of thrombocytopenia (100 K) post-COVID-19 infection and no significant medical history.

Vital signs were blood pressure: 153/102 mmHg, heart rate: 88 bpm, SpO2: 96%, and afebrile. Abdominal examination revealed mild tenderness. Fetal ultrasound showed a single fetus with a positive heart rate, fundal placenta, oligohydramnios (AFI 3 cm), fetal weight of 450 g, and absent end-diastolic flow on Doppler.

She was admitted for further evaluation and stabilization. Laboratory results indicated Hb: 11.8 g/dl, platelets: 46 K, uric acid: 6.9 mg/dl, BUN: 11 mg/dl, creatinine: 0.65 mg/dl, SGPT: 28 U/l, SGOT: 43 U/l, LDH: 234 U/l, proteinuria +2, and a protein-to-creatinine ratio of 11.8.

The patient had severely elevated blood pressure, requiring intravenous antihypertensive medications, including labetalol, hydralazine, and magnesium sulfate. During the first six hours following the patient's admission to the hospital, her worsening liver function tests (LFTs): SGPT: 90 U/l, SGOT: 188 U/l, LDH 620 U/l, and severe abdominal pain developed associated with mild vaginal bleeding necessitated an urgent termination of pregnancy, achieved through medical and mechanical preparation followed by evacuation and curettage. Immediate pregnancy termination was prioritized due to the patient’s deteriorating condition, characterized by severe hypertension, elevated liver enzymes, thrombocytopenia, and vaginal bleeding. Urgent termination was necessary to prevent further maternal morbidity and potential mortality. Medical approaches to HELLP syndrome are non-invasive and allow for gradual stabilization, but risks include prolonged harm to maternal health and potential fetal demise. Surgical approaches can quickly prevent deterioration and remove the placenta, that is why it was the chosen way; however, it carries risks such as infection, hemorrhage, and anesthesia complications.

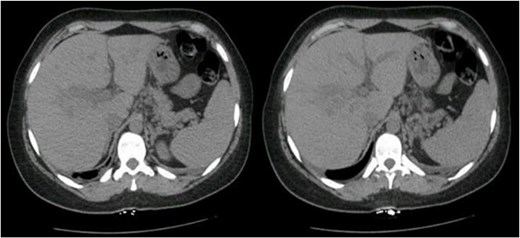

Postoperatively, her liver enzyme level continued to increase. Abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) with IV contrast revealed multiple ill-defined, non-enhancing liver lesions, the largest measuring ~2.7 cm in segment VII, suggestive of hepatic infarction with mild periportal edema (Fig. 1). The liver appeared normal in size and shape with no focal lesions.

Abdominal and pelvic CT with IV contrast showed multiple scattered, ill-defined, and non-enhancing liver lesions, the largest measuring ~2.7 cm in segment VII.

The patient received supportive multidisciplinary intensive care, and LFTs returned to normal by postoperative day 30. Her blood pressure returned to normal after 50 days of multiple antihypertensive medication regimens, primarily calcium channel blockers and beta-blockers.

Discussion

Pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders contribute significantly to maternal and perinatal mortality globally [4]. Preeclampsia, characterized by new hypertension and proteinuria after 20 weeks, includes conditions such as gestational hypertension and can progress to severe forms such as eclampsia and HELLP syndrome [4]. There are two types of preeclampsia: early-onset (before 34 weeks) and late-onset (after 34 weeks). The late-onset is rare but linked to a higher risk of HELLP syndrome and mortality [5]. Preeclampsia accounts for 2% to 8% of pregnancy complications, resulting in over 50 000 maternal deaths and 500 000 fetal deaths globally [4]. The pathophysiological causes of preeclampsia remain elusive. However, the consensus currently indicates this is due to vascular placental invasion [6]. Elevated liver enzymes in preeclampsia are believed to stem from endothelial cell damage, which decreases prostacyclin and increases thromboxane levels, causing liver vasoconstriction, hepatic hypoxia, necrosis, and hepatocyte degeneration [7]. Severe preeclampsia could be advanced to HELLP syndrome [1].

Screening strategies for early-onset HELLP syndrome may include regular monitoring of blood pressure, urine protein, complete blood cell count, in particular platelet count, and liver function throughout pregnancy. Additionally, the use of ultrasound and Doppler studies is important for assessing fetal well-being and placental health [8].

The prevalence of HELLP syndrome ranges from 0.5% to 0.9%. Approximately 70% of cases present between 28 and 37 weeks of pregnancy, while the rest occur within the first week after delivery [1]. HELLP syndrome occurring early, before 24 gestational weeks (GWs) is extremely rare, and patients often exhibit underlying maternal disease or fetal abnormalities [1].

Several pregnancy-related problems have characteristics comparable to HELLP syndrome, such as acute fatty liver of pregnancy, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura/hemolytic uremic syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, and anti-phospholipid syndrome (APS) [9].

The clinical features of HELLP syndrome typically involve pain in the right upper quadrant or epigastric area (65%), nausea and vomiting (35%), and headaches (30%) [10]. In addition, symptoms such as headaches, alterations in vision, and those linked to thrombocytopenia like mucosal bleeding, hematuria, petechial hemorrhage, or petechiae have also been documented. Hypertension and proteinuria are found in the majority of patients; however, hypertension is absent in 12%–18% of cases, and proteinuria might be absent in 13% of individuals [10].

The mortality rate of women with HELLP syndrome ranges from 0% to 24%, while the rate of perinatal fatalities can reach as high as 37% [1]. HELLP syndrome is associated with a 1% risk of maternal mortality and a variable risk of maternal morbidity depending on the complication, disseminated intravascular coagulation (15%), premature placental abruption (9%), pulmonary edema (8%), acute kidney injury (3%), and liver dysfunction and bleeding (1%) [11].

HELLP syndrome paired with liver infarction is very rare because of the liver’s unique dual blood supply. The majority of liver infarction cases occur due to disruptions in arterial blood supply to the liver, often caused by pregnancy-induced hypertension, APS, ischemic hepatitis, and portal vein thrombosis [12].

Complicated eclampsia is managed mainly with stabilization, including ventilator support, vasopressor support, pain control, monitoring of volume status, and nutritional support. As these patients can rapidly deteriorate, they are best managed at tertiary care centers with appropriate maternal and neonatal intensive care units. Then, the appropriate time of pregnancy termination should be determined according to the clinical state and suspected outcome improvement. HELLP syndrome that develops in the early second trimester is more likely to result in poor prognosis for maternal and neonatal health, which necessitates termination to interrupt the deterioration course and improve predicted intrauterine fetal complications.

In the mid-trimester, a combination of mifepristone and repeated doses of prostaglandins provides a safe and effective alternative to dilatation and evacuation.

Liver infarction presents with nonspecific signs, such as sudden upper abdominal pain, fever, jaundice, and elevated liver aminotransferases [12]. A liver biopsy helps to differentiate it from other conditions, and imaging tests are crucial for diagnosis. Abdominal CT is particularly useful in managing HELLP syndrome to rule out hepatic hematoma. In this case, liver infarction was attributed to HELLP syndrome [12]. Rupture usually occurs in the right hepatic lobe, causing right upper abdominal pain radiating to the back, shoulder discomfort, anemia, and low blood pressure [12].

The management of HELLP syndrome depends on the patient’s clinical status. Hemodynamically stable patients may be treated conservatively with high-dose dexamethasone, antihypertensive agents, and magnesium sulfate. Unstable patients should undergo perihepatic packing and should be transferred to a specialist liver unit for surgical intervention. Planned delivery within 48 hours of diagnosis is recommended to prevent severe maternal morbidity [12]. Our patient’s history of thrombocytopenia after COVID-19 may have worsened her disease severity, as low platelet counts can increase bleeding risk and complicate the management of preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome [13].

Conclusion

The occurrence of HELLP syndrome at an early gestational age below the fetus viability level is an extremely rare condition, but obstetricians must be vigilant about it because this rapidly progressing disease might endanger a mother's life. Therefore, a timely diagnosis and pregnancy termination are essential.

Author contributions

Derar I.I. Ismerat: The supervisor, patient care, drafting, critical revision, and approval of the final manuscript.

Barah K. S. Alsalameh: The supervisor, patient care, drafting, critical revision, and approval of the final manuscript.

Raneen T. M. Farash: Data collection, data interpretation and analysis, critical revision, and approval of the final manuscript.

Bayan Qnaibi: Data collection, data interpretation and analysis, critical revision, and approval of the final manuscript.

Amal Mahfoud: Drafting, critical revision, approval of the final manuscript, and corresponding.

Afnan W. M. Jobran: Drafting, critical revision, and approval of the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors declare that they have obtained patient consent.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.