-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Shahbakht Ilyas, Andrea Winthrop, Sean Bennett, Preduodenal portal vein causing symptomatic duodenal obstruction in an adult: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 4, April 2025, rjaf229, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf229

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Preduodenal portal vein (PDPV) is a congenital anomaly where the portal vein (PV) crosses anterior to the first part of the duodenum. It is commonly associated with other congenital anomalies, typically presenting as a duodenal obstruction in infancy. While rare, PDPV can be diagnosed in adulthood, but is usually asymptomatic and found incidentally during surgery or on imaging. We present a case of chronic postprandial abdominal pain, occasional vomiting, and early satiety in a middle-aged female due to PDPV causing a partial duodenal obstruction. She also had malrotation of the bowel, partial agenesis of the dorsal pancreas, and azygous continuation of the inferior vena cava. We performed a laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy to bypass the obstruction caused by PDPV, resolving the patient’s preoperative symptoms, now with over 3 years’ follow-up. Persistent and unexplained abdominal complaints in adults warrant thorough investigation for uncommon causes such as PDPV and other congenital anomalies.

Introduction

Preduodenal portal vein (PDPV) is a rare congenital anomaly typically seen in the pediatric population as a cause of duodenal obstruction. The condition was first described in 1921 by Harry O. Knight at the University of Texas, Galveston [1]. The normal course of the PV is posterior to the duodenum, as the superior mesenteric vein meets the splenic vein behind the pancreatic neck and continues superiorly. During embryonic development, it is formed due to the obliteration of the caudal segment of the right and the cephalad segment of the left vitelline veins, along with the caudal and cephalad interconnecting veins [2]. PDPV is formed when there is a variation in this process, specifically the atrophy of the caudal and middle interconnecting veins and the left vitelline vein [2]. In adults, it is most often asymptomatic and found incidentally on imaging or during surgery [3, 4]. We present a case where PDPV was found as a cause of partial duodenal obstruction in an adult with chronic abdominal symptoms.

Case report

A 61-year-old female, who has provided informed consent for this report to be published, presented with a history of postprandial epigastric pain. This was longstanding, reportedly present to some degree as far back as adolescence, but had worsened in the past 5 years. She described it as a dull ache that would radiate to the back and would occur consistently after every meal. It would last around 6 h into the evening and would resolve the next morning. This pain was associated with recurrent episodes of vomiting, shortly after eating, alongside bloating, and nausea. She endorsed a decrease in her appetite and early satiety. She described her bowel movements as loose and occasionally having a yellow hue, but no symptoms suggesting occult or obvious bleeding or fat malabsorption. She denied any pruritis, jaundice, or urinary changes. She also did not endorse any weight loss, fever, or chills.

Her past medical history includes long-standing dyspepsia, for which she underwent multiple unremarkable endoscopies and unsuccessful trials of proton-pump inhibitors and prokinetic medications. She underwent a cholecystectomy 5 years ago after which she found some symptomatic relief, but the symptoms recurred after about half a year. She had a remote history of a single episode of mild pancreatitis requiring hospitalization ~20 years ago. She also had anxiety, hyperlipidemia, and had undergone carpal tunnel release and breast reduction surgery. She had a 14 pack-year smoking history and drank alcohol occasionally.

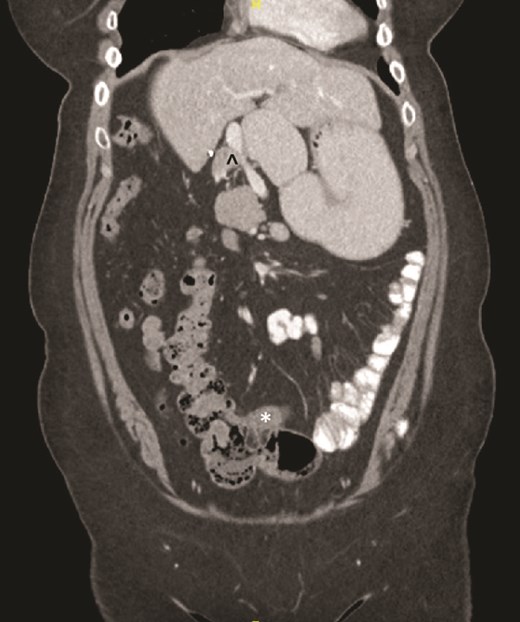

On examination, the abdomen was soft but mildly distended. Bowel sounds were heard, and the epigastrium was mildly tender. Standard bloodwork was normal. Review of an abdominal computerized tomography (CT) scan from 4 years prior showed congenital malrotation of the bowel, with the small bowel to the left of the midline and colon entirely to the right (Fig. 1). There was partial agenesis of the dorsal pancreas (Fig. 2), azygous continuation of the inferior vena cava (IVC), a retroaortic and retrocrural left renal vein, and an unremarkable spleen alongside some splenules. The PV traversed anterior to the first part of the duodenum (Fig. 3). There was relative narrowing of the distal stomach and the duodenum was nondilated.

Terminal ileum (*) seen entering cecum with completely right-sided colon and left-sided small bowel visible. PDPV also seen (^) causing partial duodenal obstruction.

Partial agenesis of the dorsal pancreas (*). Superior mesenteric vein (^) seen to the left of the superior mesenteric artery.

Preduodenal PV seen crossing the duodenum (D) causing partial obstruction.

An esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) was performed, without any mucosal abnormalities. Endoscopic intubation of the duodenum was somewhat more challenging than a typical EGD; however, there were no typical findings of gastric outlet obstruction such as retained food. Given her symptoms, radiographic and endoscopic findings, a diagnosis of partial duodenal obstruction secondary to PDPV was made. We consented her for a diagnostic laparoscopy, possible Ladd’s procedure, and gastrojejunostomy. At laparoscopy, the PDPV could easily be identified coursing anterior to the duodenum, which was distended. The bowel was run, with the small intestine occupying the left side of the abdomen, and the entire colon on the right. No significant congenital bands were identified. A side-to-side stapled gastrojejunostomy was performed in order to bypass the partial duodenal obstruction. The surgery and the postoperative period in the hospital were uneventful. She was discharged home on postoperative Day 3 with a prescription for pantoprazole to reduce the risk of marginal ulcer at the gastrojejunostomy. She reported feeling well on her 1 and 4-month postoperative follow-up appointments with complete resolution of her preoperative symptoms. The pantoprazole was discontinued at the 4-month follow-up as the risk of a marginal ulcer was deemed to be low.

At 1-year follow-up she reported a return of epigastric abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) symptoms. The symptoms of GERD tended to be at night in bed. She restarted her pantoprazole on an as needed basis for the past two weeks, and noticed some mild improvement. After this follow-up, we restarted the pantoprazole twice per day. EGD was arranged the following month, and at the time of scope she noted continued improvement of her symptoms while on pantoprazole. The EGD demonstrated no esophagitis, and normal gastric mucosa. The anastomosis, however, appeared strictured but able to be passed with the gastroscope. The small bowel limbs were normal without evidence of ulcer. The anastomosis was balloon dilated up to 20 mm. The scope could be passed beyond the pylorus into the first part of the duodenum, which was dilated, however it could not be passed into the second part of the duodenum. At 1 month following, the EGD her symptoms had improved completely. She was maintained on twice daily pantoprazole, and at follow-up 3 months later she continued to do well and her pantoprazole was decreased to once daily. She was recommended to likely remain on that drug life-long. She continued to be symptom free at the 2- and 3-year postoperative marks.

Discussion

PDPV is a rare condition, commonly associated with other congenital anomalies. In previous reports, it has presented with situs inversus, bowel malrotation, annular pancreas, biliary atresia, IVC anomalies, polysplenia syndrome, etc. [5–7]. Most cases of PDPV are diagnosed in childhood and infancy due to duodenal obstruction causing severe symptoms. Our case is unique because PDPV is usually asymptomatic in adults. The reason for the delayed diagnosis in our patient could be due to the partial nature of the obstruction not causing significant malnutrition or weight loss. Her congenital anomalies, including the PDPV, were reported on her prior CT scans, but likely were not thought to be contributing to her symptoms.

In a series of 54 cases of PDPV, 20 were diagnosed in adults with 6 of those thought to be causing duodenal obstruction [8]. In the 34 pediatric patients, PDPV was thought to be causing duodenal obstruction in 8, with 15 having other causes of duodenal or small bowel obstruction. This is significant because in our patient the intestinal malrotation was also considered as a potential contributing factor to her symptoms. Thus, our operative approach included an exploration for congenital Ladd’s bands, although no significant ones were found. A gastrojejunostomy was in line with previous reported operations to bypass a PDPV in adults [9, 10]; however, the typical operation for a pediatric patient would be a duodenoduodenostomy or duodenojejunostomy to avoid long-term complications related to bile reflux.

A PDPV needs special consideration during duodenal and biliary tract surgery as there is an increased risk for ligation, tearing, division, and thrombosis due to excessive handling [1]. This is especially important during emergent laparotomy where cross-sectional imaging may not be performed prior to surgery. In our case, a CT scan was beneficial as the PDPV was readily visible traversing anterior to the duodenum and identifiable as a potential cause of duodenal obstruction. This was further confirmed during EGD when there was difficulty passing the gastroscope into the first part of the duodenum. This approach is similar to previous case reports where CT imaging and an EGD were performed prior to surgery [11, 12].

This case report emphasizes the need to investigate potential congenital anomalies in adults, especially where there are long-standing and recurrent abdominal symptoms without another explanation. The presence of a PDPV alone should not necessarily prompt surgical intervention, but only if symptoms are concordant with radiologic and endoscopic findings. It also highlights PDPV as a rare but important anomaly to be aware of prior to gastroduodenal or biliary tract procedures, as failure to recognize it preoperatively or intraoperatively could be fatal, or lead to significant morbidity.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.