-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Vivien Nguyen, Corey Rowland, Travers Weaver, An unusual and incidental diagnosis of acute promyelocytic leukaemia through eye casualty, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 4, April 2025, rjaf228, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf228

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This case study reports a young man with hypertension who presented to eye casualty and was incidentally diagnosed with acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APML). Dilated fundus examination showed multiple retinal flame haemorrhages from the optic discs with scattered exudates bilaterally. Optical coherence tomography showed left cystoid macular oedema. He had preserved vision bilaterally and was systemically well with no constitutional symptoms. This case report is the first of our knowledge that reports on this unusual clinical presentation of APML. The patient successfully completed 29 days of induction all-trans-retinoic acid/arsenic trioxide therapy with repeat bone marrow biopsy showing haematological remission. Ophthalmic review 2 months later revealed resolution of retinal haemorrhages and cystoid macular oedema. Retinal haemorrhages may be the initial and only manifestation of APML. A full blood count should be considered in patients who present to eye casualty with haemorrhagic retinopathy of unknown aetiology.

Introduction

Acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APML) is a rare but life-threatening subtype of acute myeloid leukaemia (AML). It is uncommon for a patient to be diagnosed with a haematological malignancy via eye casualty without any systemic symptoms, especially one that is as rapid and life-threatening as APML. This case report is the first of our knowledge that reports on this unusual clinical presentation of APML.

Case report

A man in his mid-30s presented to a metropolitan eye casualty following 6 days of blurred vision in his left eye. He reported no recent illness, travel, fevers, weight loss, or stressors in his life. Past ocular and medical history were largely unremarkable, besides from a recent diagnosis of hypertension 2 months prior. He was a non-smoker, non-alcohol drinker, and denied intravenous drug use.

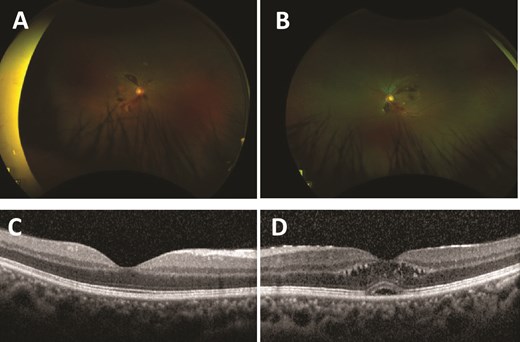

Unaided visual acuity (VA) was right 6/4.8 + 1 (logMAR −0.1) and left 6/7.5 (logMAR 0.1). Intraocular pressures were within normal limits. There was no relative pupillary afferent defect. Ishihara plates, red saturation, and brilliance testing were normal bilaterally. Anterior segment examination was unremarkable bilaterally. Dilated posterior segment examination (with 1% tropicamide and 2.5% phenylephrine) revealed multiple retinal flame haemorrhages of varying sizes superiorly and inferiorly from the optic discs with scattered exudates (Fig. 1A and B). There was no optic disc swelling bilaterally. Optical coherence tomography showed left subretinal and intraretinal fluid, indicative of cystoid macular oedema (CMO) (Fig. 1C and D). His vital signs were within normal limits.

Ultra-widefield red–green retinal image of the right eye (A) and left eye (B), with scattered retinal haemorrhages extending from the optic nerve head. Optical coherence tomography of the macula of the right eye (C) and left eye (D). Right eye (C) shows a normal macula. Left eye (D) shows retinal thickening with intraretinal cystic areas and a foveal pigmented epithelial detachment.

Given the patient’s presentation and background of hypertension, a tentative diagnosis of hypertensive retinopathy was made; however, basic blood tests (full blood count, serum electrolytes, urea/creatinine) was performed to exclude haematological abnormality. Pathology results displayed severe pancytopaenia: haemoglobin 64 g/l (male normal range: 130–180 g/l), white cell count 0.6 × 109/l (normal range: 4.5–11.0 × 109/l), platelets 3 × 109/l (normal range: 150–400 × 109/l), haematocrit 0.19 (male normal range: 0.40–0.54), neutrophils 0.05 × 109/l (normal range: 2.00–7.50 × 109/l), lymphocytes 0.42 × 109/l (normal range: 1.20–4.00 × 109/l), monocytes 0.00 (normal range: 0.20–1.00 × 109/l), eosinophils 0.01 × 109/l (normal range: <0.50 × 109/l). Immediate haematology admission was arranged. Empirical treatment was initiated which included two units of platelets and two units of packed red blood cells. He was commenced on all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) 45 mg/m2, arsenic trioxide (ATO) 0.15 mg/m2, oral prednisone 0.5 mg/kg daily, and intravenous (IV) piperacillin/tazobactam 4 g/0.5 g QID post-blood culture collection. A bone marrow biopsy was obtained the following day. There was a blast population comprising 81% of total cells. The blast count showed abnormal intermediate promyelocytes with a folded nucleus and occasional Auer rods. The translocation of the promyelocytic leukaemia (PML) gene and retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARA) gene was detected, indicating positive PML–RARA fusion and is a diagnostic hallmark of APML.

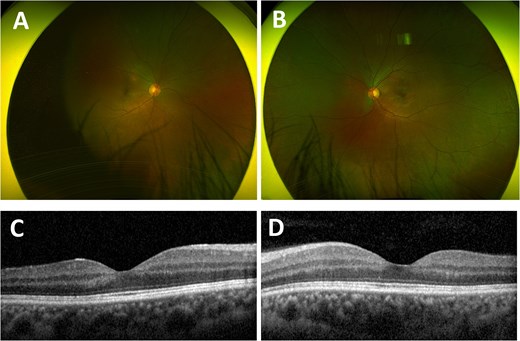

The patient successfully completed 29 days of induction ATRA/ATO therapy. Repeat bone marrow biopsy showed haematological remission with count recovery, and no PML–RARA fusion was detected. Ophthalmic review 2 months later revealed unaided right VA 6/6 (logMAR 0) and left VA 6/6 (logMAR 0), with resolution of retinal haemorrhages and left CMO (Fig. 2).

Ultra-widefield red–green retinal image of the right eye (A) and left eye (B) 2 months after completion of induction therapy, with resolved haemorrhagic retinopathy. Optical coherence tomography of the macula of the right eye (C) and left eye (D) 2 months after completion of induction therapy, both showing normal maculae.

Discussion

APML is rare and has <100 diagnoses in Australia each year [1, 2]. It is characterized by a chromosomal translocation between chromosomes 15 and 17 (15;17)(q24;q21), resulting in the expression of the PML–RARA fusion protein [2]. Like all haematological malignancies, APML can affect multiple organs, including the eye.

There have been many reported cases where patients have been diagnosed with chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) based on ocular findings, as most individuals are initially asymptomatic due to the insidious disease progression of CML [3–7]. However, few cases have been described wherein APML was diagnosed in this way, as the disease develops far more rapidly with profound physical symptoms associated with severe pancytopaenia [8, 9]. In previous cases which described ocular findings leading to a diagnosis of APML, these patients also had significant systemic symptoms with extensive vision deficit. Terada et al. [9] described a 35-year-old man with hand movements’ vision from vitreous haemorrhage and associated widespread subcutaneous haemorrhages, while Lee and Hwang [8] report a systemically unwell 14-year-old boy with fever, bruises, and light perception vision from haemorrhagic retinal detachment. Although Zhuang et al. described a case of leukaemic retinopathy being the initial manifestation of AML, the patient also presented with fever and significant vision loss (VA 6/120; logMAR 1.3) [10]. Contrastingly, our patient had preserved vision bilaterally and was systemically well with no constitutional symptoms. This case report is the first of our knowledge that reports on this unusual clinical presentation of APML, emphasizing the importance of challenging diagnostic bias.

A prompt diagnosis of APML is time-critical, as patients are at risk of disseminated intravascular coagulation and hyperfibrinolysis, which can lead to fatal intracranial and pulmonary haemorrhages [2, 11]. Mainstay management of leukaemic retinopathy involves treating the underlying haematological malignancy [12]. The introduction of ATRA and ATO has been ground-breaking for APML survivorship and acts by differentiating APML promyelocytes into fully mature granulocytes. These treatments have allowed a formerly fatal acute leukaemia to evolve into one that is highly curable [11]. Unwanted sequalae can, however, arise from these treatments such as differentiation syndrome [13]. This lethal complication is caused by the cytokine release from the promyelocyte differentiation of ATRA/ATO treatment [13]. Similarly to our patient, prophylactic corticosteroids are initiated alongside Day 1 of treatment and are continued until the end of the induction period in order to reduce the risk of differentiation syndrome.

Although modern treatment with ATRA/ATO has improved mortality outcomes, the promising long-term survivorship of patients who complete induction treatment remains impacted by the significant early mortality rates reaching up to 30% within 30 days [14]. A 2021 study by Dhakal et al. concluded that this is likely due to the challenge of detecting leukaemic emergencies [15]. Immediate administration of ATRA is therefore extremely important, however, is only possible if healthcare practitioners, including ophthalmologists, recognize the clinical and morphological characteristics of APML [1, 11, 13]. In this case report, haemorrhagic retinopathy and CMO were the first and only presenting signs of APML, with the laboratory confirmed pancytopaenia allowing for prompt diagnosis and treatment. A full blood count should therefore be considered in patients who present with haemorrhagic retinopathy of unknown aetiology.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.