-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Marie L Jacobs, Kevin M Sigley, William O’Malley, Case report of mesenteric abscess following laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in the setting of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 4, April 2025, rjaf198, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf198

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We report the management of a 38-year-old female with a history of ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt who underwent laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) and presented with infected mesenteric abscess. The patient underwent LRYGB and was discharged on postoperative day (POD) #1. She sustained a syncopal event on POD #15, with workup revealing a mesenteric abscess. She underwent operative drainage of the abscess, small bowel resection and revision of her jejunojejunostomy. The VP shunt was visualized intraoperatively and after discussion with the neurosurgery team, externalized. She was treated with empiric intravenous antibiotics, and serial shunt cultures. After persistently negative shunt cultures, she underwent re-internalization of the shunt on POD #12 after drainage and was discharged home. Complications of bariatric surgery in patients with VP shunts can be successfully managed with a high index of clinical suspicion and timely multi-disciplinary cooperation.

Introduction

Bariatric surgery is commonplace in the United States, with sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass being the two most performed procedures [1]. Comorbidities associated with obesity include idiopathic intracranial hypertension and hydrocephalus. These can be treated with the placement of a ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt to drain excess cerebrospinal fluid into the peritoneal cavity, thereby decreasing intracranial pressure [2, 3].

Case description

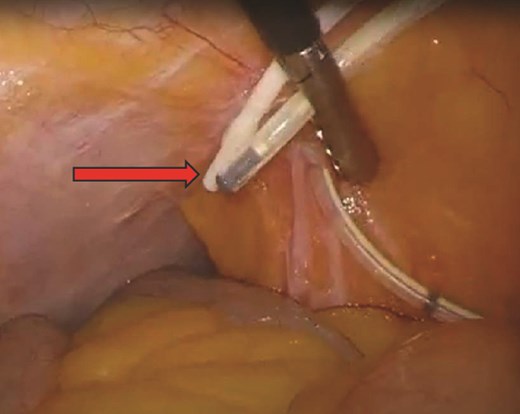

Our patient is a 38-year-old female with a medical history of cerebral palsy, congenital cerebral ventricular dilation and hydrocephalus with VP shunt placement in infancy, sleep apnea and morbid obesity (body mass index (BMI) 43 kg/m2) who underwent laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) and was discharged on postoperative day (POD) #1. On POD#15, she sustained a syncopal event and presented to the emergency department. She was found to be tachycardic to 105 beats/min with epigastric tenderness and a leukocytosis of 15.6 (thou/μL). Computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 4.8 × 10.1 cm air- and fluid-containing collection worrisome for abscess versus contained small bowel perforation (Fig. 1). She underwent diagnostic laparoscopy converted to exploratory laparotomy, revealing an infected hematoma with abscess in the mesentery of the proximal common channel and adjacent ischemic bowel without evidence of perforation. She underwent drainage of the abscess and resection of the compromised bowel, including her jejunojejunostomy (JJ) and 40 cm of the common channel. A new JJ was created. Intraoperatively, two VP shunt catheters were inspected and consultation from neurosurgery was obtained (Fig. 2). One shunt was determined to be nonfunctional and was removed. The functional shunt was externalized. Postoperatively, she was admitted to the intensive care unit for shunt monitoring, placed on cefepime, metronidazole and vancomycin, and her shunt was serially cultured. Intraabdominal fluid cultures from the operating room were polymicrobial, including Klebsiella oxytoca, Citrobacter freundii complex, Enterococcus faecalis, Parvimonas micra, and Prevotella. After persistently negative shunt cultures and 12 days of intravenous antibiotics, her shunt was re-internalized on POD#14 (POD#28). She completed a 14 day total course of antibiotics and was discharged home. She was most recently seen for an annual visit and is doing well, having lost 33% of her total body weight, and 58% of her excess body weight.

Discussion

There are several neurologic conditions that can be treated with VP shunts, such as hydrocephalus (as in our patient) and idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH). Congenital hydrocephalus, most commonly due to obstruction of cerebrospinal fluid drainage, presents with increased intracranial pressure and enlargement of the cerebral ventricles on imaging [4]. IIH, formerly known as pseudotumor cerebri, presents with elevated intracranial pressure and papilledema without an identifiable precipitant or structural changes noted on imaging [5]. IIH has a known association with obesity, and appears to be increasing in tandem [6, 7]. Treatment focuses on decreasing intracranial pressure with medication, medical or surgical weight loss, or VP shunt placement [8, 9]. Bariatric surgery, like other abdominal surgery, is not without the possibility of complication. This includes anastomotic leak, intraabdominal abscess or infected hematoma, or missed enterotomy. Intraabdominal infection in a patient with a VP shunt presents the possibility of ascending infection causing shunt dysfunction, central nervous system infection, or seizure [10]. There are no reports in the literature on management or outcomes of intraabdominal infection following bariatric surgery in patients with VP shunts. However, reports in the setting of other intraabdominal pathology are instructive.

A meta-analysis of 49 patients with appendicitis in the setting of VP shunts was described by Hallen et al.: 10 patients required shunt externalization, 11 patients had shunt infections, and two patients expired [11]. Waldman et al. report a series of patients with variable sources of infection: two patients with appendicitis, one perinephric abscess, one appendiceal abscess, one case of bowel ischemia, one pancreatic pseudocyst, and one case of Clostridioides difficile colitis. Four patients underwent surgery and two underwent percutaneous intervention; none developed peritonitis or shunt complications [12]. Grant et al. report on a spontaneous knotting of VP shunt tubing in a 13-year-old boy, resulting in 135 cm of bowel necrosis; the shunt was exteriorized at the time of bowel resection [13]. Morinaga et al. describe their experience with a 49 year-old woman with a VP shunt who experienced migration of a non-functional shunt into the bowel, resulting in an intra-abdominal abscess managed with shunt exteriorization, washout and antibiotics [14].

Our patient underwent laparotomy, small bowel resection and revision of the JJ anastomosis, abdominal washout, and shunt externalization due to concern for risk of ascending infection in the setting of frank purulence. The decision for conversion to laparotomy was made due to the need for improved visualization, exploration of all four quadrants, and thorough washout. Bowel resection was performed due to concern for ischemic bowel presenting continued nidus of infection. It is possible that if the patient’s abdomen had been left open and a second look operation performed, the bowel may have improved in character. However, the intraoperative appearance of the bowel was favored to represent an irrecoverable situation. The patient had sufficient remaining small bowel that the concern for short gut syndrome was low. Timely consultation with the neurosurgical team intraoperatively was helpful in making the decision for externalization of the shunt. The outcome in this patient was excellent, and the authors attribute this to flexibility in approach and excellent multidisciplinary patient care.

Conclusions

Given the association between IIH, hydrocephalus and obesity, bariatric surgeons can expect to encounter patients with VP shunts in their practice. Intraabdominal complications should be promptly managed to obtain source control and prevent central nervous system infection. Depending on the nature and magnitude of the infection and the patient’s clinical status, laparoscopy versus laparotomy can be performed, broad antibiotic coverage should be initiated, and patients should be carefully evaluated for shunt externalization. Bowel resection in bariatric patients, particularly those who have previously undergone RYGB or duodenal switch should be carefully considered to ensure the patient is not at undue risk for short gut syndrome.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the neurosurgical team involved for their collaboration in the care of this patient.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.