-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Toshiyuki Yamaguchi, A giant epidermal cyst preoperatively diagnosed by core needle biopsy, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 2, February 2025, rjaf088, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf088

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Epidermal cysts are common benign cutaneous tumors that usually appear as slowly growing lumps of up to a few centimeters in diameter. They rarely grow >5 cm in diameter and are referred to as giant epidermal cysts. Although soft tissue tumors >5 cm are recommended for imaging examination and biopsy preoperatively, biopsy of giant epidermal cysts has rarely been performed because of the complications that may arise when non-absorbable materials are released from the cyst. Here, I report a case of a giant epidermal cyst in which a core needle biopsy was performed, and the cyst was preoperatively diagnosed. After core needle biopsy, adverse effects that influenced the clinical course did not arise. Clinicians should not hesitate to perform the core needle biopsy, which can mitigate perioperative uncertainty in giant epidermal cysts.

Introduction

Epidermal cysts are common benign cutaneous tumors that usually appear as slow-growing lumps with sizes ranging from millimeters to a few centimeters [1]. Definitive treatment involves the surgical excision of the cyst, including its wall, to reduce recurrence [1]. Judged as epidermal cysts by history taking and visual palpation, most cases are removed without formal imaging examination [2]. They rarely grow >5 cm in diameter and are referred to as giant epidermal cysts [2]. Although imaging examination and biopsy of soft tissue tumors >5 cm are recommended preoperatively [3], giant epidermal cysts have rarely been biopsied [4]. I report a case of a giant epidermal cyst preoperatively diagnosed using core needle biopsy (CNB).

Case presentation

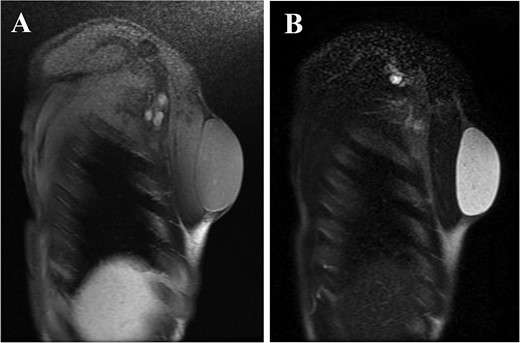

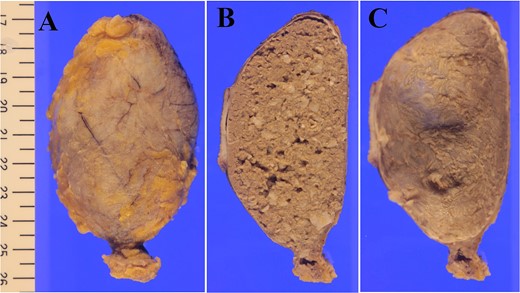

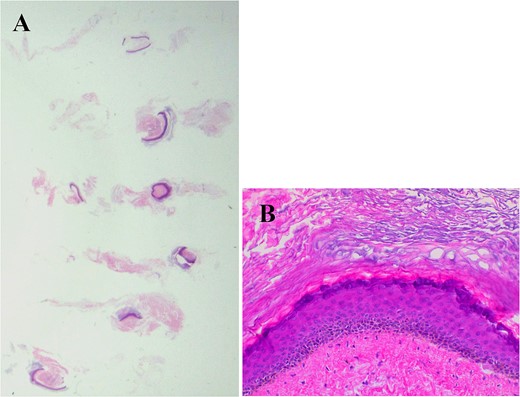

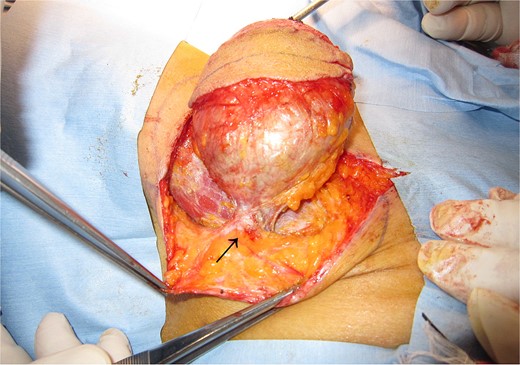

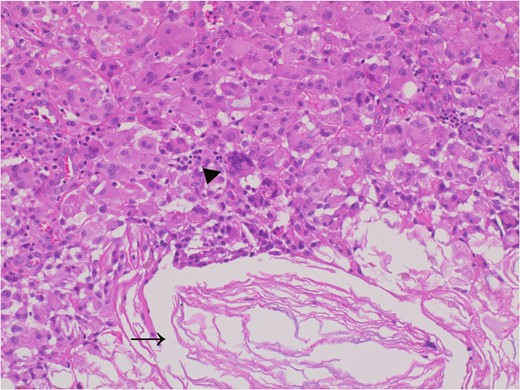

A 61-year-old man presented to the outpatient breast clinic with a painless lump in his right pectoral region. The lump was first noticed 40 years earlier at the size of a small fingertip and gradually increased. The lump was approximately 90 mm in diameter, well-defined, and dome-shaped. The overlying skin appeared glossy with no visible puncta (Fig. 1). Erythema or bruising was not observed. On palpation, the lump was non-tender and doughy with no localized temperature increase. It was not fixed to underlying tissue. On ultrasound imaging, the lump showed a hypoechoic and well-circumscribed oval mass containing variable echogenic foci and filiform anechoic areas without color Doppler signals (Fig. 2). The lump was located in the subcutaneous fat layer, with extensive dermal apposition. In sagittal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the lump showed a unilocular and well-defined cystic mass (70 × 40 × 90 mm) (Fig. 3A and B). The cyst content showed an isointense signal relative to the muscle with no enhancement in the sagittal enhanced T1-weighted image (Fig. 3A), and a hyperintense signal in the T2-weighted image (Fig. 3B). Ultrasound-guided percutaneous CNB was performed, and six core specimens containing cystic walls ware sampled (Fig. 4A). The cystic wall was lined with mature stratified squamous epithelium with a granular layer and did not contain an adnexal structure (Fig. 4B). In addition, many laminated or basket-woven keratin layers were sampled. These findings ware consistent with those of an epidermal cyst. The mass was excised under general anesthesia. The mass was well-defined and did not adhere to the surrounding structures, except for a portion of the CNB (Fig. 5). The mass was easily excised. The formalin-fixed mass was covered with a thick white fibrous capsule (Fig. 6A), which was filled with grey substances, such as bean curd residue, in the cross-section (Fig. 6B). After the removal of the contents, the internal surface of the capsule was crepey, and no nodules were observed (Fig. 6C). The definitive pathological diagnosis was an epidermal cyst without any malignancy. The adhesive region revealed keratin, which flowed outside the cyst, and a granulomatous response to keratin with multinucleated giant cells (Fig. 7). No complications or recurrences were observed during the one-year follow-up after surgery.

Photograph showing the lump of right pectoral region which was 90 mm in diameter, well-defined and dome-shaped.

Ultrasound imaging showing hypoechoic and well-circumscribed oval mass containing variable echogenic foci and filiform anechoic areas.

Six core needle specimens containing cystic walls were sampled by core needle biopsy, hematoxylin, and eosin stain, ×2 magnification (Fig. 4A). Cystic wall was lined by mature stratified squamous epithelium with granular layer and did not contain adnexal structure, hematoxylin, and eosin stain, ×20 magnification (Fig. 4B).

The mass was well-defined and easily removed. There was slight adhesion at core needle biopsy site (allow).

The adhesive region revealed keratin (allow) which flowed outside the cyst and granulomatous response for keratin with multinucleated giant cells (allow head), Hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×20 magnification.

Discussion

There is a possibility of 20% malignancy in any soft-tissue lesion >5 cm in diameter [2]. In addition to history-taking and visual palpation, ultrasound imaging should be considered as the initial triage imaging modality, followed by MRI for soft tissue tumors measuring >5 cm [3]. However, there is a limit to imaging alone in reducing differential diagnosis because many types of soft tissue tumors exit, and cytopathological examination is a pivotal process in narrowing down differential diagnosis in addition to diagnostic imaging [5]. Although all giant epidermal cysts are subject to cytopathological examination considering their size [6], many giant epidermal cysts are excised without preoperative cytopathological examination [4]. For cystic lesions, specimens of the cystic wall that provide the highest yield for pathological diagnosis should be sampled [7]. Although fine needle aspiration cytology has occasionally been performed for epidermal cyst, it does not provide histologic information about the cystic wall but mainly offers cytologic information about the cyst content [8, 9]. CNB or open biopsy is necessary to obtain cystic wall specimens. Open biopsy is performed only when CNB does not correlate with the clinical presentation and imaging or cannot be diagnosed by CNB alone. Image-guided CNB is the gold standard for soft tissue tumor biopsy. However, CNBs for giant epidermal cysts have rarely been performed [4]. Hesitancy in performing CNB is due to concerns about complications that may arise when non-absorbable materials are released from the cyst [4]. Although CNB was performed in this case, adverse effects that influenced the course of treatment did not occur, except for adhesions at the biopsy site. Although Rahman et al. reported a case of an epidermal cyst that became inflamed at the puncture site following abscess formation after CNB [10], serious accidents have not been reported in giant epidermal cysts in which CNBs were performed [11–14]. However, it must be taken into consideration that (i) CNB is performed under ultrasonography to sample the cystic wall specimen [7], (ii) a stab incision is not made at the skin that contacts the cystic wall, which can lead to skin breakdown [15], and (iii) biopsy route should be within the area of subsequent resection [15].

Conclusion

Clinicians should include giant epidermal cysts in the differential diagnosis of soft tissue tumors >5 cm in size [13] and should not hesitate to perform image-guided CNBs to mitigate perioperative uncertainty for giant epidermal cysts.

Conflict of interest statement

There are no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding was received for this case report.

Ethical statement

The patient was informed that data from the research would be submitted for publication, and consent was obtained.