-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Raju Sah, Sushil Bahadur Rawal, Srijan Malla, Jyoti Rayamajhi, Pawan Singh Bhat, Bleeding pseudoaneurysms in postoperative upper gastrointestinal surgery patients: a single -center experience, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 2, February 2025, rjaf048, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf048

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Visceral artery pseudoaneurysms are rare but life-threatening complications following upper gastrointestinal (GI) surgery. This case series reviews six patients (male-to-female ratio 3:3) who developed pseudoaneurysms, presenting with diverse clinical manifestations. Four patients (66.6%) experienced bleeding, including hemoperitoneum and upper GI bleeding, with one also reporting nausea and vomiting. Two patients (33.3%) developed anastomotic site leakage, leading to hemoperitoneum in one and bile-induced intra-abdominal infection in the other. The pseudoaneurysms involved the proper hepatic artery (n = 3), common hepatic artery (n = 2), right hepatic artery (n = 1), jejunal artery (n = 1), and splenic artery (n = 1). All patients underwent interventional radiology procedures, with angioembolization performed in each case. Recurrent bleeding required re-embolization in three cases: two from previously treated sites and one from a new pseudoaneurysm. Bleeding occurred between the 5th and 27th postoperative days, and one patient succumbed. Early diagnosis and timely endovascular management are critical for improved outcomes in these patients.

Introduction

Bleeding from pseudoaneurysm is a rare but severe complication reported after laparoscopic cholecystectomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy, and liver transplantation. It often presents as delayed massive hemorrhage, sudden or intermittent, with high mortality [1]. Predicting and managing this complication is crucial in postoperative care for upper abdominal surgeries. Limited data exists on its incidence, and no consensus on optimal treatment has been established. Traditionally managed by surgical resection and ligation, advancements now include less invasive methods like transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) and endovascular stent grafts, which are equally effective, particularly for high-risk surgical patients [2–4]. This retrospective study reviews our experience managing ruptured pseudoaneurysms and evaluates TAE's effectiveness.

Methods

This retrospective case series reviewed patients with pseudoaneurysm bleeding following upper gastrointestinal surgery at our institution. Data collected included demographics, surgical procedures, complications, pseudoaneurysm location, diagnosis timing, clinical presentation, diagnostic methods, management, and outcomes. A literature review was also conducted via PubMed using terms like ‘pseudoaneurysm AND hepatic artery,’ ‘visceral pseudoaneurysm,’ and ‘pseudoaneurysm management.’ Relevant studies were summarized to compare literature findings with our case series outcomes.

Case 1

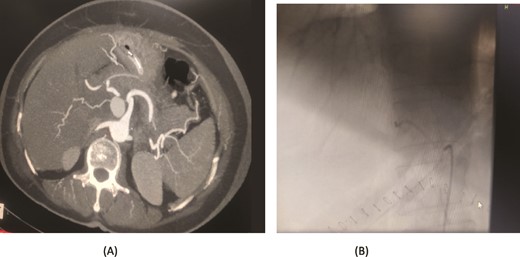

A 57-year-old female underwent a distal pancreatectomy for a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumo. On the 13th postoperative day, the patient presented in a state of shock and intraperitoneal bleeding. A contrast-enhanced CT angiogram revealed the presence of a pseudoaneurysm originating from the splenic artery. The patient underwent endovascular coil embolization of the splenic artery and bleeding stopped and was discharged 3 days following the procedure (Fig. 1).

Case 1. (A) Angiogram pseudoaneurysm from splenic artery. (B) Angioembolization of splenic artery with coil

Case 2

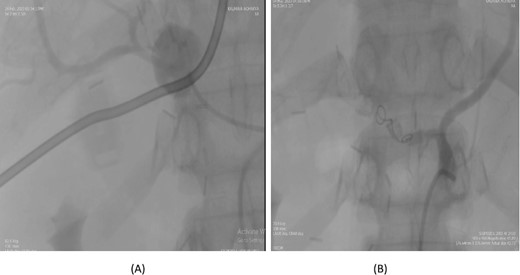

A 56-year-old female underwent a pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) for pancreatic head adenocarcinoma. On the 6th postoperative day, she presented with nausea and vomiting. A contrast-enhanced CT scan revealed the presence of a pseudoaneurysm originating from the common hepatic artery. Angioembolization was promptly performed to control the bleeding. The procedure was successful, and the patient recovered well postoperatively. At follow-up, the patient was doing fine with no further complications (Fig. 2).

Case 2. (A) CT angiogram showing pseudoaneurysm CHA. (B) Angioembolization of CHA with gel foam

Case 3

A 36-year-old female underwent a Whipple’s pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. On the fifth postoperative day, she experienced massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding, confirmed by endoscopy showing massive clots. A contrast-enhanced CT angiogram revealed a pseudoaneurysm from the proper hepatic artery, with abrupt truncation of the left gastric artery. Angioembolization was performed, with coil embolization of the proper hepatic artery and super selective embolization of the left gastric artery using gel foam. However, 32 days later, the patient experienced re-bleeding. A follow-up CT angiogram showed dislodging of the coil in the proper hepatic artery, allowing contrast through the coil and into the pseudoaneurysm. A second angioembolization repositioned the coil and used 70% glue and Lipiodol for embolization. Post-procedure, the patient had no further complications and was stable at follow-up (Fig. 3).

Case 3. (A) Angiogram shows pseudoaneurysm from proper hepatic artery. (B) Angioembolization of proper hepatic artery with coil.

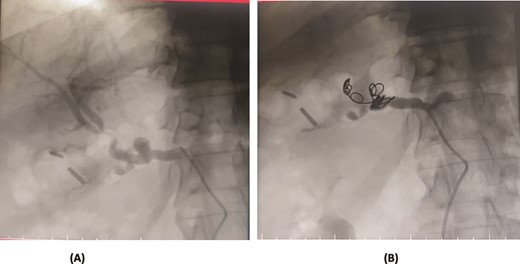

Case 4

A 66-year-old male underwent an extended cholecystectomy with bile duct excision and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy for suspected gallbladder carcinoma. However, the histopathological examination revealed xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. Postoperative patient develops anastomotic site leakage so was discharged with abdominal drain. On the 9th postoperative day, during follow-up for bile leak with an abdominal drain in situ, a contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen identified a pseudoaneurysm at the bifurcation of the gastroduodenal artery and proper hepatic artery. Angioembolization was performed using two coils and 50% glue. The abdominal drain was subsequently removed, and the patient recovered without further complications, doing well at follow-up (Fig. 4).

Case 4. (A) CT scan – pseudoaneurysm at bifurcation of gastroduodenal artery and proper hepatic artery. (B) Embolization of gastroduodenal artery and proper hepatic artery.

Case 5

A 76-year-old male underwent distal gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection for gastric cancer. On the 27th postoperative day, he developed massive upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding, which was confirmed by an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGIE) showing large clots. A contrast-enhanced CT angiogram revealed a pseudoaneurysm arising from the common hepatic artery (CHA) and proper hepatic artery (HA). Angioembolization was promptly performed using two coils, successfully controlling the bleeding. Despite this intervention, the patient experienced re-bleeding 12 days later. Repeat UGIE again demonstrated massive clots, and CT angiography confirmed the presence of a pseudoaneurysm at the CHA. A second angioembolization was conducted using four coils, which successfully halted the bleeding. The patient’s condition stabilized, and he was closely monitored with no further complications noted (Fig. 5).

Case 5. (A) Angiogram shows a pseudoaneurysm at common hepatic artery and another at hepatic artery proper. (B) Common hepatic artery was selected and embolization performed with two coils and gelfoam

Case 6

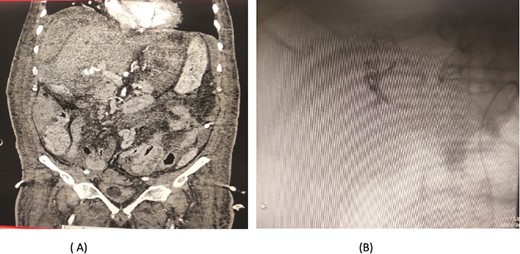

An 80-year-old male diagnosed with Mirizzi syndrome type 3 underwent a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy and cholecystectomy. His postoperative course was complicated by anastomotic site leakage on the 3rd postoperative day (POD). On the 14th POD, the patient presented with a sudden decrease in hemoglobin levels and per rectal (PR) bleeding. A CT angiogram revealed active bleeding from a branch of the jejunal artery, which was controlled through angioembolization. Two days after the first embolization, the patient developed intraperitoneal bleeding. A repeat CT angiogram showed active bleeding from the right hepatic artery, and a second angioembolization was performed to control the bleeding. Despite successful management of the bleeding episodes, the patient developed hospital-acquired pneumonia, which led to his deterioration. Unfortunately, the patient expired on the 30th POD (Fig. 6).

Case 6. (A) CT angiogram showing pseudoaneurysm and bleeding from right hepatic artery. (B) Embolization performed with coils.

Results

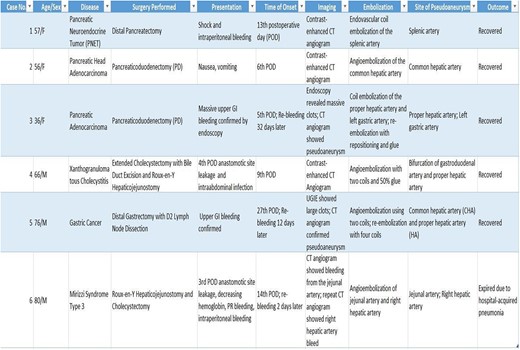

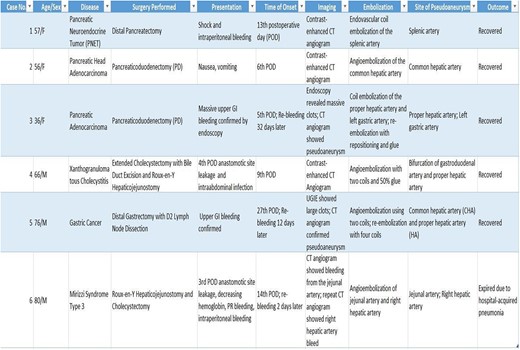

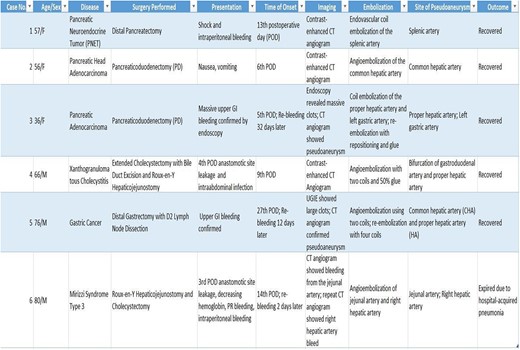

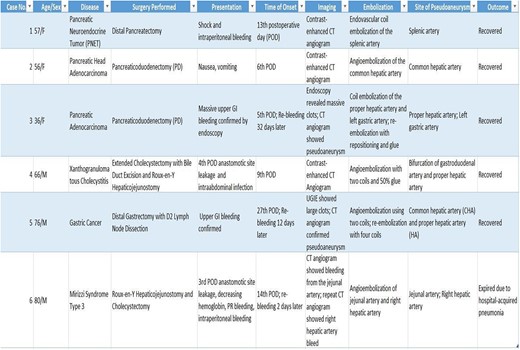

Six patients (three male and three female) with a median age of 61 years (range 36–80) were diagnosed with a visceral arterial PA after surgery. PA location included the following arteries (Table 1): the proper hepatic artery (n = 3), common hepatic artery (n = 2), right hepatic artery (n = 1), jejunal artery (n = 1), and splenic artery (n = 1).

Patient, age, gender, disease, surgery procedure, presentation, time of onset, imaging, treatment, site of pseudoaneurysm, outcome.

|

|

Patient, age, gender, disease, surgery procedure, presentation, time of onset, imaging, treatment, site of pseudoaneurysm, outcome.

|

|

The original procedures included the following: Pancreaticoduodenectomy (n = 2), distal gastrectomy (n = 1), extended cholecystectomy with hepaticojejunostomy (n = 1), Hepaticojejunostomy (n = 1) and distal pancreatectomy (n = 1).

Bleeding was a prominent feature, affecting four (4/6, 66.6%) patients: two presented with hemoperitoneum, and two had upper gastrointestinal bleeding. One experienced nausea and vomiting. Two patient (2/6, 33.3%) developed anastomotic site leakage from their initial procedures in which one presented with hemoperitoneum and other patient had intra-abdominal infection related to bile leakage.

A CT angiogram was done in all six patients, revealing the presence of a pseudoaneurysm. All six patients underwent interventional radiology procedures, with angioembolization performed in each case. Two cases involved rebleeding from previously embolized sites, while one arose from a new pseudoaneurysm at a different location, necessitating re-embolization. The bleeding occurred between 5th and 27th postoperative days. There was one mortality.

Discussion

Pseudoaneurysms occur when arterial wall continuity is disrupted, leading to blood leakage into surrounding tissues and forming a fibrous tissue sac. Unlike true aneurysms, which involve the dilation of the entire vessel wall, pseudoaneurysms result from partial wall damage. They can arise due to inflammation, trauma, tumors, or surgical interventions [1]. Post-abdominal surgery, gastrointestinal bleeding due to pseudoaneurysm formation is rare but carries significant risks of severe complications and death [5].

Hepatobiliary surgery, in particular, is a major contributor to hepatic artery pseudoaneurysms, especially with the growing adoption of aggressive treatments for liver tumors and transhepatic interventions. When pseudoaneurysms rupture, the bleeding path depends on their location. Extra-hepatic pseudoaneurysms may cause hemoperitoneum, while intrahepatic ones can result in haemobilia by allowing blood to enter the biliary tree. Blood can also flow into the duodenum, mimicking gastrointestinal bleeding. Slow bleeding prevents blood and bile from mixing, forming clots that obstruct bile ducts, potentially causing jaundice, cholangitis, or pancreatitis. Haemobilia typically presents with abdominal pain, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and jaundice, though patients may not exhibit all three symptoms. Delayed bleeding can occur due to gradual pseudoaneurysm expansion before rupture, complicating early detection [1, 2].

Several mechanisms contribute to pseudoaneurysm formation. Local infections, like intra-abdominal abscesses, weaken the arterial wall. Other factors include arterial erosion from pancreatic, biliary, or intestinal fistulas, vascular trauma during surgeries like lymphadenectomy, tight arterial ligation, and preoperative radiotherapy, which damages blood vessels [6–11].

Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial to improving outcomes. A drop in haemoglobin or a persistent low-grade fever in the second or third postoperative week may signal local sepsis or pseudoaneurysm formation. Septic complications often precede severe hemorrhages, which carry high mortality risks. Monitoring for minor bleeds in septic patients is vital, as these can indicate an impending major hemorrhage [1].

Diagnostic evaluation is guided by patient history and symptoms. Contrast-enhanced CT angiography (CTA) is the gold standard for pseudoaneurysm detection after upper GI surgery, providing detailed visualization of the pseudoaneurysm, its relationship to the surgical site, and complications like hematoma or bile leakage. CTA effectively localizes arterial bleeding, crucial for endovascular or surgical intervention planning [1].

Upper endoscopy is occasionally used for gastrointestinal bleeding but is less effective in patients with altered anatomy, such as Roux-en-Y reconstructions or esophagectomies [12]. Emergency endoscopy can be challenging and may not reveal deep or inaccessible pseudoaneurysms. Postoperative ultrasound detects fluid collections or hematomas but has limited sensitivity due to surgical dressings, gas, or adhesions. Multi-detector CT angiography (MDCTA) offers comprehensive vascular imaging and excels at identifying pseudoaneurysms missed by conventional CT or ultrasound. MDCTA's precise localization of bleeding vessels supports effective treatment planning, reducing complications and improving outcomes [1].

Management prioritizes bleeding control and maintaining biliary flow. Alongside resuscitation, transfusions, and antibiotics for sepsis, TAE has emerged as a widely accepted treatment for visceral pseudoaneurysms [13].

Emergency reoperations in hemodynamically unstable patients are high-risk, with elevated morbidity and mortality due to inflammation and dense adhesions, especially following multiple surgeries. Another challenge is the anatomical inaccessibility of the bleeding vessel, especially in patients who have had multiple prior surgeries [1].

Up to 95% of bleeding pseudoaneurysms can be managed with embolization. Superselective arterial catheterization allows embolization near the bleeding site using materials like gelatin sponge or microcoils, or covered stents for venous bleeding or arteriovenous fistulas. Embolization is a minimally invasive option, achieving success rates of 63%–79% [5]. It also addresses re-bleeding and surgical ligation failures, particularly in high-risk patients [1]. Post-embolization monitoring for re-bleeding, infection, or bile leakage is essential, and follow-up imaging may be needed in high-risk patients to confirm stability at the embolization site.

Visceral arterial pseudoaneurysms (PAs) are rare but significant complications of abdominal surgeries, often presenting with delayed hemorrhage. Our findings align with studies by Cheung et al. (2007) [1], Boufi et al. (2013) [14], and Sanchez Arteaga et al. (2016) [15], which identify bleeding as the predominant clinical manifestation. Hemorrhage may manifest as hemoperitoneum, GI bleeding, or haemobilia. In our cohort, 66.6% of patients exhibited bleeding, while others presented with bile leakage or infection. Similar patterns were noted by Sanchez Arteaga et al. [15], who observed haemobilia and GI tract bleeding in many cases.

Pseudoaneurysms frequently involved the proper hepatic, common hepatic, and splenic arteries, consistent with Sanchez Arteaga et al. [15] and Boufi et al. [14], who highlighted these arteries, especially following pancreaticoduodenectomy and gastrectomy. In our cohort, median bleeding onset was 16 days post-surgery, aligning with Boufi et al. [14] mean onset of 23 days, emphasizing the delayed nature of this complication.

Angioembolization achieved initial hemostasis in all cases but had a 50% recurrence rate in our cohort. Two cases involved re-bleeding from previously embolized sites, and one resulted from a new pseudoaneurysm, necessitating re-embolization.This relatively high recurrence rate may be attributed to the complexity of vascular anatomy, particularly in the proper hepatic artery, where coil migration or incomplete embolization is more likely. Boufi et al. [14] similarly reported a 50% recurrence rate, while Sanchez Arteaga et al. [15] noted complications requiring surgery in 36% of cases. The integration of stent grafting with angioembolization, as explored by Sanchez Arteaga et al. [15], has demonstrated promise, particularly in anatomically suitable cases, a finding also supported by Boufi et al. [14]

Despite advancements, pseudoaneurysm-associated mortality remains high. In our series, 16.7% of patients succumbed to complications, similar to Boufi et al. [14] 14–20% mortality. Sanchez Arteaga et al. [15] reported a higher 41.6% mortality, likely reflecting more complex cases or delayed treatment. Across studies, recurrent bleeding and procedure-related complications highlight the need for close postoperative monitoring and timely interventions.

Conclusion

Visceral arterial pseudoaneurysms have delayed onset and significant morbidity. While angioembolization is effective, its recurrence risk highlights the need for improved techniques. Stent grafting, especially in patients with favorable anatomy, presents a promising option for more definitive treatment. Future efforts should focus on enhancing interventional methods, early detection, and managing complications like infections and bile leaks to improve outcomes and reduce mortality.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.