-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Orlando Sanchez-Orbegoso, Jhon E Bocanegra-Becerra, Jorge Rabanal-Palacios, Hector Yaya-Loo, Single frontotemporal approach for microsurgical clipping of bilateral ophthalmic artery aneurysms: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 2, February 2025, rjaf042, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf042

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Bilateral ophthalmic aneurysms represent a distinct niche of brain aneurysms located in a complex skull base region. When considering surgical treatment, a single-stage approach is often advantageous to minimize operative time, tissue manipulation, and damage to neural and vascular structures compared to a two-stage surgery. Nonetheless, this procedure is not exempt from risks, given that thorough knowledge, preoperative and intraoperative judgment can be necessary to reduce the significant risk of bilateral vision loss. Thus, a tailored approach often is needed. In this study, we present the case of a 53-year-old female who was diagnosed with bilateral ophthalmic aneurysms during the work-up for chronic headaches. Because of the growth pattern and imminent risk of rupture, she underwent elective microsurgical treatment. A frontotemporal approach ipsilateral to the most lobulated aneurysm was performed. Both aneurysms were successfully clipped in a single craniotomy. Her postoperative imaging demonstrated adequate clipping and an uneventful clinical course. Our case outlines the feasibility of a single approach and contributes to the tailored selection for patients when considering microsurgical treatment for these complex lesions.

Introduction

With an estimated worldwide prevalence of 3.2%, intracranial aneurysms (IAs) are vascular dilations that can lead to subarachnoid hemorrhage and detrimental clinical outcomes [1–3].

Multiplicity is a feature that can occur in about one-third of IAs [4]. The pathophysiology for this presentation is complex, but commonly associated factors include hypertension, smoking, age, and family history [4]. In addition, roughly 40% of multiple aneurysms are located in a symmetric or similar bilateral configuration of parent vessels, which confers the designation of mirror aneurysms [3–7].

Paraclinoid aneurysms constitute IAs located near the anterior clinoid process, with ophthalmic aneurysms being the most frequent type in this area [8]. The deep location in the skull base often challenges the surgical access of these aneurysms [8]. Moreover, when mirror ophthalmic aneurysms are present, neurosurgeons frequently face the complex decision-making process of approaching through a single or bilateral craniotomy [5].

In this case report, we present the surgical nuances of a patient who received treatment for bilateral ophthalmic aneurysms via a single craniotomy.

Case report

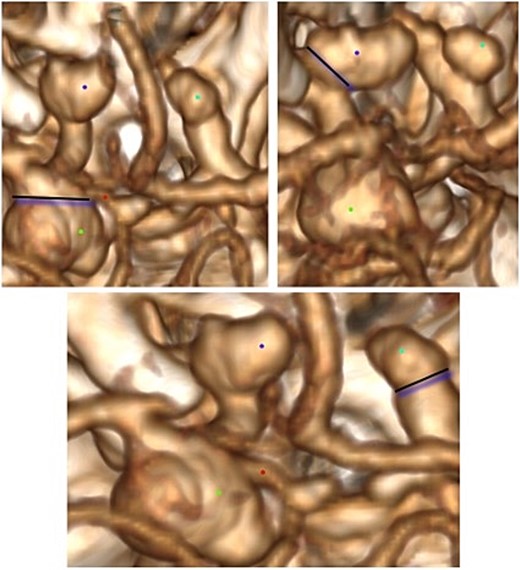

A 53-year-old female patient presented with a 2-year course of chronic headaches, described as intermittent, located in the frontal region, and with partial response to over-the-counter analgesics. Her medical history was not relevant for neurological disorders. A cerebral computed tomography angiography (CTA) revealed three cerebral aneurysms, two in a mirror configuration at the ophthalmic segment of the internal carotid artery (ICA) and the other at the left posterior communicating aneurysm (Fig. 1).

Three-dimensional imaging reconstruction of the circle of Willis from a superior view. Bilateral ophthalmic aneurysms are marked in blue, and the dysmorphic posterior communicating aneurysm is labeled in green.

We decided to perform a left frontotemporal approach for clipping, considering the more prominent and lobulated lesion on the left side. If anatomical features in the operative field appeared favorable, we expected to place a contralateral clip at the right ophthalmic aneurysm.

Operative note

Surgery was started by placing the patient in a standard position for a left frontotemporal craniotomy. No complications emerged during the anesthesia induction. A left arcuate incision was performed, followed by a standard left frontotemporal craniotomy, extradural anterior clinoidectomy, and a C-shaped dural opening.

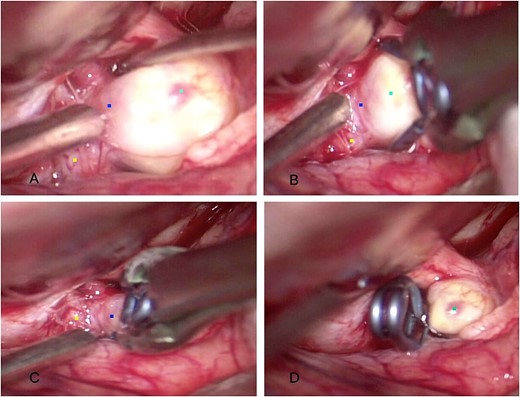

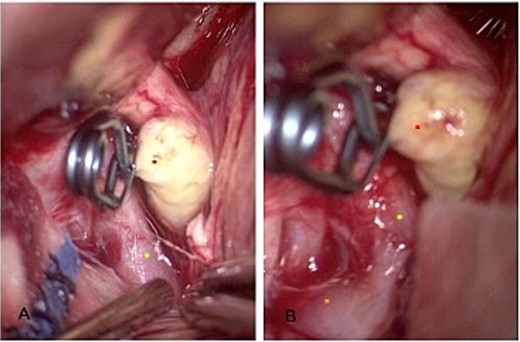

The brain parenchyma appeared relaxed, facilitating the opening of the Sylvian fissure. Then, the left optic nerve and ICA were identified. A medium-sized saccular aneurysm came into view (Fig. 2) with an atheromatous wall in the neck and aneurysmal sac. Gently dissection of the surrounding aneurysm was performed, and the ophthalmic artery was identified. Then, a 7-mm straight clip was placed at the aneurysm neck, which resulted in the aneurysm exclusion from circulation. We reviewed the configuration of the dysmorphic posterior communicating aneurysm (Fig. 3), which compromised the posterior communicating and choroidal arteries, thus making clipping unplausible because of the imminent risk of arterial branch occlusion. Next, we dissected the chiasmatic cisterns and identified the optic chiasm. The contralateral optic nerve became visible along with the contralateral ophthalmic aneurysm.

Intraoperative findings. (A) Dissection of the saccular ophthalmic aneurysm (light blue) emerging from the internal carotid artery (yellow). (B, C) A 7-mm straight clip was placed at the aneurysm neck (blue). (D) Final configuration of the aneurysm clip.

Revision of the surrounding anatomy. (A) The left communicating segment of the internal carotid is shown with the aneurysm adequately clipped. (B) The ipsilateral dysmorphic posterior communicating aneurysm came into view.

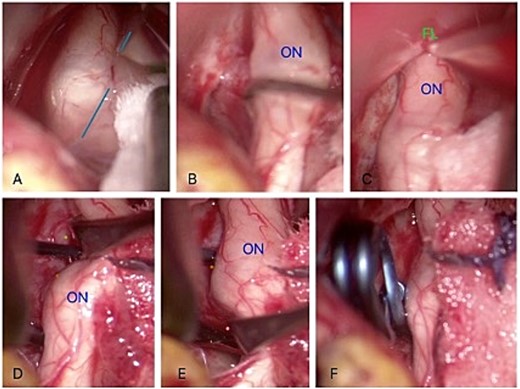

The right falciform ligament and lamina terminalis were opened for better exposure to the aneurysm (Fig. 4). Then, a 9-mm semi-curved clip was placed cautiously to avoid occluding the ophthalmic artery. Finally, the brain parenchyma remained relaxed, and closure was performed in a standard fashion. The patient was admitted to the neurointensive care unit in a stable condition without vasopressors. A postoperative CTA showed complete exclusion of mirror aneurysms, no signs of bleeding, and absent edema (Fig. 5). She is currently awaiting management of her posterior communicating aneurysm.

Intraoperative findings. (A) Dissection of the contralateral sylvian fissure (sky-blue line). (B) Dissection of the contralateral optic nerve (ON). (C) Dissection of the falciform ligament (FL). (D) Identification of the right ophthalmic aneurysm neck (brown) and contralateral ophthalmic artery (green). (E) Visualization of the inferior part of the aneurysm neck (orange) and perforating arteries. (F) Placement of the 9 mm semi-curved clip.

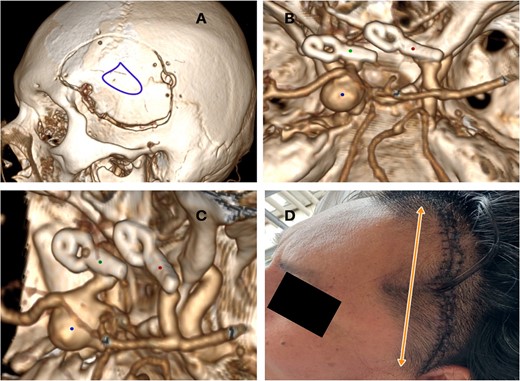

Postoperative imaging and course. (A) Left frontotemporal craniotomy (purple). (B) Postoperative three-dimensional computed tomography angiography showed adequate clip placement. (C) 7 mm straight clip (green), 9 mm semi-curved clip (red). (D) Wound without signs of infection or edema.

Discussion

The distribution of mirror aneurysms is heterogeneous. A large case series involving 3120 patients revealed that they could be commonly present at the middle cerebral artery (34%) and the noncavernous portion of the ICA (32%) [4]. When aneurysms involve ophthalmic aneurysms bilaterally, the treatment decision-making is often multifaceted, given the complex location near the compacted and deep-seated paraclinoid region [8].

Approaching these lesions can be done in a single or two-stage craniotomy. However, appropriate treatment selection is required to reduce excessive manipulation of the optic nerve and minimize the associated morbid course of surgery [7, 9, 10]. A single or unilateral craniotomy can be advantageous in reducing the overall surgical time, minimizing the trauma to the brain and optic apparatus, and shortening the recovery period from a two-stage surgery [11, 12]. Preoperative assessment of the visual function and configuration of aneurysms is relevant in selecting the side and angle of clipping for both aneurysms [12]. Nonetheless, as demonstrated in our case, the intraoperative anatomic configuration and state of brain parenchyma relaxation often determine the appropriateness of clipping the contralateral aneurysm. In addition, comprehensive knowledge of the basal cisterns, neural structures, bone protrusions, and vascular structures cannot be underestimated to exclude both aneurysms [5, 8, 10, 12, 13].

For example, in a case series of 11 patients, Nacar et al. demonstrated the feasibility of a single approach for bilateral ophthalmic aneurysms by achieving a complete occlusion rate of 96% and good neurological outcomes after a mean follow-up period of 2 years [14]. The authors outlined that among the surgical nuances, rarely a second anterior extradural clinoidectomy is required for contralateral aneurysms. Moreover, a favorable dome projection for contralateral aneurysms includes a medial, superior, superior medial, or inferior medial position. On the other hand, those contralateral aneurysms projecting laterally or superolateral can be obscured by the optic nerve and, thus, increase its manipulation and damage [14]. Consequently, neurosurgeons must outweigh the benefits of a single approach versus the major risk of bilateral vision loss.

Conclusion

Our case outlines the feasibility of a single approach and contributes to the tailored selection for patients when considering microsurgical treatment of these complex lesions.

Acknowledgements

Patient consent was obtained.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: O.S.O., J.R.P., H.Y.L.; Methodology: O.S.O., J.E.B.B., J.R.P., H.Y.L.; Investigation: O.S.O., J.E.B.B.; Writing—original draft preparation: O.S.O., J.E.B.B.; Writing—review and editing: O.S.O., J.E.B.B., J.R.P., H.Y.L.; Supervision: J.R.P., H.Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding was received for this article.

Data availability

Not applicable.