-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Danah Aldulaijan, Abdulrahman Subaih, Turki Almuhaimid, Deena Abdulhadi Alnuaimi, Rare case of skull metastasis from endometrial carcinoma sparing lymph nodes: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 12, December 2025, rjaf987, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf987

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Endometrial cancer is common especially among females. It could disseminate through direct, lymphatic, and hematogenous spread. On the other hand, cutaneous metastases are extremely rare. We reported a case of a 70-year-old female with a history of early-stage endometrial carcinoma (Stage IB, Grade 2) who developed a rare skull metastasis sparing lymph nodes. Given the patient's poor performance status and comorbidities, she was deemed unfit for systemic chemotherapy. Palliative care was initiated, focusing on symptom management. This case underscores the importance of considering atypical metastatic presentations in endometrial cancer and highlights the challenges in diagnosis and management.

Introduction

Endometrial carcinoma commonly spreads by local extension and lymphatic routes, and distant metastases especially to bone or skin are extremely rare. Involvement of the skin or skull usually indicates extensive disease and is associated with a poor prognosis [1]. In this report, we highlight the unusual occurrence of a skull metastasis in a 70-year-old woman with early-stage (Stage IB, Grade 2) endometrial carcinoma sparing the lymph nodes. The CT of the brain shows metastasis to the brain. A brain biopsy confirmed that there was brain metastasis sparing lymph nodes.

Case presentation

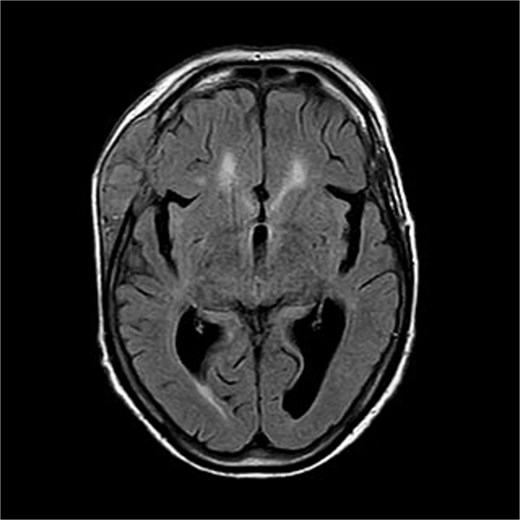

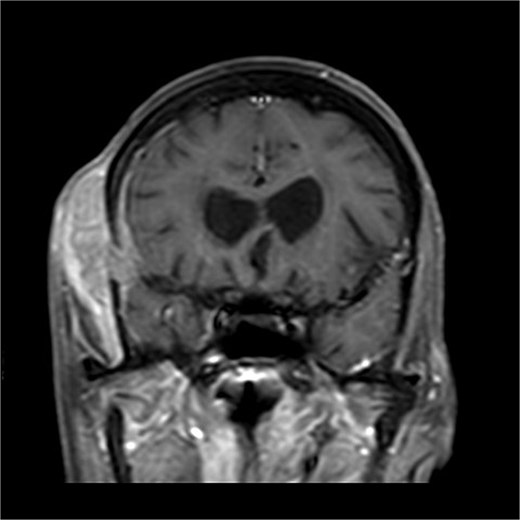

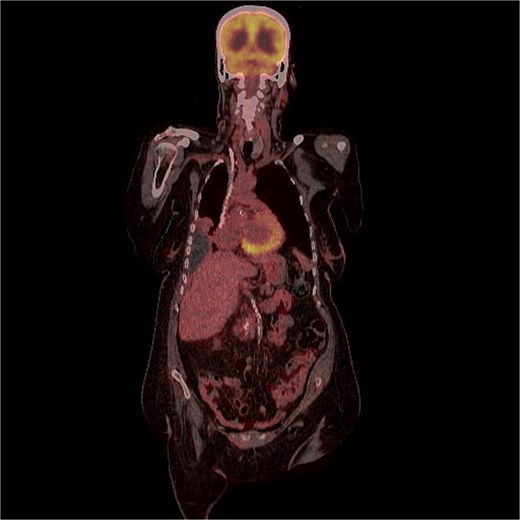

A 70-years old female came to the tertiary hospital, with a gradually enlarging right frontal-temporal scalp swelling associated with headache. She presented to the ER with abnormal movement, described by the son was gazing upward toward specific point with right upper limb jerky movement lasting for 15 s and frothy secretions, not responding during the event. Whole event lasted for 40–45 s. No reported pre-event symptoms and for post event patient was back to baseline after one-to-one hour and half. The son noticed this event repetitively happens on exertion, positioning the patient from lying to siting position, and before the dialysis sessions. Regarding her surgical and medical history, she is a known case of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, end-stage renal disease on dialysis, and cardiac disease with low ejection fraction. In addition, the patient had undergone a total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy under spinal anaesthesia in for endometria carcinoma, stage IB, grade 2 and subsequently received vaginal vault brachytherapy. Upon physical examination, the patient was noted to have a large, non-tender, soft to firm swelling in the right frontal-temporal region, with no other remarkable findings. CT with contrast (Figs 1 and 2) of the brain revealed metastasis to the right frontal bone and the greater wing of the sphenoid, with large extra-cranial and small intracranial soft tissue components with no parenchymal brain lesions were observed. A brain biopsy confirmed that there was fibromuscular and adipose tissue with focal necrosis and atypical cells, with crushed and scarse atypical cells likely neoplastic or reactive. Also, PET CT scan (Figs 3 and 4) confirms that there was brain metastasis sparing lymph nodes. Given her poor status and significant comorbidities, she was deemed unfit for systemic chemotherapy. The patient received palliative radiotherapy to the scalp lesion 20 Gy in 5 fractions.

There is a bone lesion involving the right frontal bone and, to a lesser extent, the right greater wing of the sphenoid, with a sizable extracranial soft tissue component in the temporal fossa measuring 5 × 1.8 × 5.4 cm in CC, TV, and AP dimensions respectively. There is also a small related intracranial extra-axial soft tissue component with associated pachymeningeal mild thickening and enhancement over the frontotemporal cerebral convexity. No obvious brain parenchymal invasion is noted, No midline shift or brain herniation. There is generalized brain tissue volume loss in the form of prominence of sulci, gyri, and ventricular system. A tiny focus of blooming effect is noted at the right cerebellar hemisphere.

There is a bone lesion involving the right frontal bone and, to a lesser extent, the right greater wing of the sphenoid, with a sizable extracranial soft tissue component in the temporal fossa measuring 5 × 1.8 × 5.4 cm in CC, TV, and AP dimensions respectively. There is also a small related intracranial extra-axial soft tissue component with associated pachymeningeal mild thickening and enhancement over the frontotemporal cerebral convexity. No obvious brain parenchymal invasion is noted, No midline shift or brain herniation. There is generalized brain tissue volume loss in the form of prominence of sulci, gyri, and ventricular system. A tiny focus of blooming effect is noted at the right cerebellar hemisphere.

FDG uptake was noted in the scalp lesion, while no other areas of abnormal uptake were identified elsewhere.

FDG uptake was noted in the scalp lesion, while no other areas of abnormal uptake were identified elsewhere.

Furthermore, patient was managed palliatively with analgesics and prophylactic antibiotics. On follow-up, her surgical site was noted to be clean with no evidence of infection.

Discussion

Endometrial adenocarcinoma is among the most prevalent gynaecological malignancies. The disease typically propagates through direct local invasion and lymphatic dissemination, primarily affecting the pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes. Although less frequent, hematogenous spread can result in distant metastases, commonly involving lungs, liver, and bones [1] The most common site is the lung (1.5%) followed by liver (0.8%) and bones (0.6%) and lastly brain (0.2%) [2]. Cutaneous metastases from endometrial carcinoma are extremely rare, and the presence of the mass on the scalp in our case suggest hematogenous rather than lymphatic spread, as was reported by others [3].

Most patients present with localized disease, with nearly 20% showing regional spread and 9% exhibiting distant metastases. According to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database and other studies, 5-year survival rates are stage-dependent. The 5-year survival rate in early-stage EC exceeds 95%, but it drops to 56%–69% in patients with loco-regional spread and plummets to 17%–20% in patients with distant metastases [4]. The median age for bone metastasis is 60 [2]. According to a systematic review study, there were 40% of cases with isolated brain metastasis without extracranial metastasis, 23% cases with isolated brain metastasis with extracranial metastasis, 9% with multiple brain metastasis without extracranial metastasis, and 28% with multiple brain metastasis with extracranial metastasis [2]. These results suggest that brain metastasis is very rare and the pathogenesis is not clear enough even in our case. A patient with recurrent endometrial cancer can initially present with an isolated scalp lesion and may have a normal pelvic exam. Thus, extensive metastatic evaluation is needed in these cases to rule out any other primary site [5]. Thus, this indicates that a whole-body imaging technique, such as a fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (F-FDG PET/CT) scan, is useful in detecting distant or atypical metastases and in guiding the diagnosis [6]. Often cutaneous metastasis from endometrial carcinoma reflects advanced spread. The sculp although highly vascular, is an uncommon site of metastasis. Its presence usually indicates disseminated disease and is associated with a poor prognosis with most patients surviving a few months after diagnosis [3]. Furthermore, according to a case report study in literature done in 2018, there are low and high grades of endometrial stromal sarcoma, and they are divided based on gene rearrangement, also the low grade can transfer to a high grade over time which will metastasis to the scalp as in this case [7].

Conclusion

This case highlights an exceptionally rare presentation of skull metastasis from early-stage endometrial carcinoma, occurring without lymphatic involvement. Such atypical distant spread emphasizes the need for clinicians to maintain a high index of suspicion when evaluating new cranial lesions in patients with a history of endometrial cancer, regardless of stage or disease-free interval. Given the poor prognosis and limited treatment options in such cases, palliative care remains essential to optimize quality of life and manage symptoms effectively.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

Ethical approval

This study did not require ethical approval as it is a case report.