-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Joseph A Attard, Joseph H Mullineux, Debasish Das, Neil Bhardwaj, Liver abscess secondary to ingested cocktail stick: a case of minimally invasive management, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 12, December 2025, rjaf959, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf959

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Liver abscess formation following foreign body ingestion is rare but may occur if the foreign body is lodged in the gastrointestinal tract and persists. Due to the rare nature of the condition, it can easily be missed at the index presentation. Furthermore, the limited number of cases described in the literature means there is no consensus on the optimal management of this condition. Initial treatment generally consists of antibiotics with or without percutaneous abscess drainage. However, referral to the regional hepatobiliary unit may also need to be considered to discuss surgical exploration and foreign body retrieval, especially if it is located within the liver parenchyma, to treat persistent sepsis or prevent abscess recurrence. We describe a case of foreign body detection in the left lobe of the liver on follow-up imaging after the index admission and subsequent elective surgical exploration and removal.

Introduction

Liver abscess formation secondary to foreign body (FB) ingestion is a rare but potentially life-threatening condition [1]. Current literature is limited to case reports and case series [2]. Blunt items may pass through the gastrointestinal tract without incident unless they cause mechanical obstruction. If they become lodged, they may erode into and perforate the gastrointestinal mucosa as a consequence of prolonged pressure [1]. More often, sharp items are involved as they cause direct trauma and perforate the gut mucosa [1]. Depending on location this may lead to peritonitis, a surgical emergency, or, more rarely, FB persistence leading to abscess formation [2]. Prompt diagnosis and treatment of the latter are crucial to prevent further complications [2]. This must be borne in mind given the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges posed by this condition without a high degree of clinical suspicion [2]. In most cases, antibiotics and abscess drainage are insufficient, and FB removal is necessary to ensure complete symptom resolution [1], often done at the index admission due to persistence of the abscess or worsening sepsis [2]. We describe a report of FB removal from the liver using a minimally invasive approach as an elective procedure.

Case report

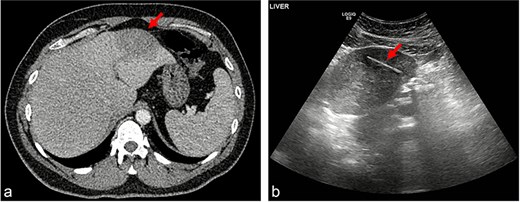

A gentleman in his 30s, previously healthy, presented to the emergency department of a district general hospital with nausea, upper abdominal pain, and fever. He had upper abdominal tenderness but no guarding, leucocytosis, and raised inflammatory markers. A computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 6-cm hypoattenuating lesion in the left liver lobe (Fig. 1a). All other observations were normal, and he was admitted for intravenous antibiotics. Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated a hepatic abscess. His symptoms and fever resolved with conservative management, and he was discharged.

(a) Hypoattenuating lesion in the left lobe of the liver; (b) linear hypoechoic structure within a hypoechoic lesion.

A follow-up outpatient ultrasound (US) scan to assess abscess resolution revealed a 4-cm linear hypoechoic structure within the liver (Fig. 1b), raising the suspicion of a FB. This finding was subsequently linked to the patient presenting to the emergency department with abdominal pain after accidentally ingesting the tip of a cocktail stick, which had broken off while eating, a few weeks before his inpatient admission. At the time, he had been well with normal bloods, a soft non-tender abdomen and normal plain radiography, and discharged with the expectation that the stick will pass through without complications.

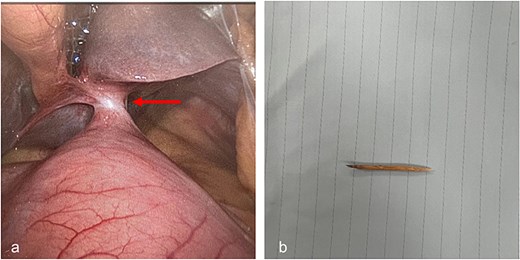

Following the US scan finding, the patient was referred to the regional hepatobiliary unit where he was subsequently admitted electively for diagnostic laparoscopy, FB removal, and liver abscess drainage. At laparoscopy, a fistula was visualized communicating between the inferior surface of segment III, and the lesser curvature of the stomach (Fig. 2a). This was disconnected using hook diathermy, and the FB was seen protruding from the liver surface, from where it was retrieved in its entirety (Fig. 2b). The gastric perforation was sealed primarily using a linear stapling device. A nasogastric tube was left until the patient tolerated a liquid diet. He was discharged on the first post-operative day, and he remained well on follow-up four weeks later.

(a) Fistulous communication between liver Segment 3 and lesser curvature of stomach; (b) retrieved cocktail stick.

Discussion

Liver abscess pathophysiology secondary to FB ingestion involves migration of the ingested FB from the gastrointestinal tract. The FB causes direct tissue damage, leading to local inflammation, perforation, and subsequent abscess formation [1]. Items associated with liver abscesses reported in the literature include toothpicks [3], fish bones [2], chicken bones [4], and dental protheses [5]. Metal wire [6], clothespin [7], sewing needle [8], a pen [9], rosemary twig [10], a lobster shell [11], and a toothbrush [12] have also been implicated. Clinical presentation can vary, and symptoms are often non-specific with many patients being unaware of having swallowed a FB. Common symptoms at presentation include abdominal pain, fever, and even jaundice [1]. Nausea, vomiting, and malaise may also be present [1]. Diagnosis is challenging, as initial imaging studies such as radiography, US and CT may not visualize the FB, although CT is considered the gold standard for diagnosis. Interestingly, in our case, it was not picked up at the initial CT but rather the follow-up US. A high index of suspicion is therefore necessary, as further diagnostic procedures such as endoscopy or exploratory surgery may be required.

There is currently no consensus on the optimal management [1]. A literature review reveals that definitive treatment involves a multidisciplinary approach tailored according to the patient’s clinical condition and location of the object [1]. Systemic antibiotics plus percutaneous and / or surgical drainage and FB removal remain the most frequently cited treatment modalities [1]. Source control is with antibiotics to control infection, with or without abscess drainage [1]. FB on cross-sectional imaging, may help assess the optimal extraction method whether this be endoscopic [13], percutaneous [14], or surgical [3]. FB retrieval removes the offending agent to prevent further complications. If this is located within the liver, referral to a hepatobiliary unit should be considered as retrieval may necessitate a liver resection [3]. The most commonly described location of migrated foreign bodies in the liver is the left lobe [1] due to its proximity to the stomach and duodenum, where the vast number of perforations occur. For this reason, FB retention should be suspected in left lobar abscesses with no apparent cause.

Surgery, both open and minimally invasive, is the most common method of FB extraction from the liver [1]. This is accompanied by drainage of the abscess and collection of fluid for microbiology to direct further antibiotic treatment [1]. In our case, minimal fluid was drained insufficient for further analysis. Laparoscopy enables a thorough intra-abdominal assessment if the site of the perforation is not known. Intra-operative US may also play a role in identifying the FB’s location, allowing for better planning of the optimal incision for open surgery should the need arise. In some instances, a liver resection may be required [3]. Interestingly, complete resolution of a liver abscess solely with conservative management, via a course of intravenous antibiotics and total parenteral nutrition, has also been described [15]. However, this does risk a protracted recovery as well as causing recurrent symptoms or future complications [15]. Long courses of antibiotics and follow-up imaging may therefore be considered in patients not fit for surgical intervention.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.