-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Julia Haugaard, Andreas Jørgensen, Karen Dyreborg, Hans Gottlieb, Subungual exostosis and osteomyelitis: a case series, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 12, December 2025, rjaf950, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf950

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Subungual exostosis (SE) is a rare benign osteocartilaginous tumor, most often affecting the great toe. While complications such as nail deformity and recurrence are known, the coexistence of osteomyelitis within SE has not previously been reported. We describe three adolescent patients with SE complicated by osteomyelitis at the same anatomical site. Diagnosis was established by clinical examination, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and intraoperative bone cultures. All patients underwent surgical excision with debridement, application of intramedullary antibiotic-loaded bone void filler, and a 6-week systemic antibiotic regimen. At follow-up, all patients showed complete resolution of infection with no recurrence or postoperative complications. This case series introduces a novel association between SE and osteomyelitis. MRI should be considered in SE cases to assess for underlying infection, and management should integrate surgical debridement, intraoperative cultures, and targeted antibiotic therapy to ensure optimal outcomes.

Introduction

Subungual exostosis (SE) is a rare, benign osteocartilaginous tumor of unknown etiology that typically occurs beneath the nail bed of the toes, particularly the great toe [1–4]. Histologically, it is characterized by a proliferation of bone and cartilage, often leading to pain, deformity, and sometimes secondary infections [1, 3, 5]. The exact cause of SE remains unclear, but it is often associated with repeated trauma, chronic irritation, or infections [1, 2, 6]. The primary treatment of SE is surgical excision [7–10].

Osteomyelitis, first described in modern medical literature by Nelaton in the 19th century, is most associated with trauma or surgical interventions [11]. However, it can also occur in the presence of predisposing factors such as chronic irritation, infections, exposure of bone tissue through skin defects, or structural abnormalities of the bone. Pathogens commonly implicated include Staphylococcus aureus and various streptococcal species. Diagnosis typically involves clinical examination, radiographic imaging, and microbiological culture. Treatment of osteomyelitis requires surgical debridement and antibiotics.

To our awareness, the co-occurrence of SE and osteomyelitis within the same anatomical site represents an underexplored clinical phenomenon. The objective of this study is to present osteomyelitis as a simultaneous condition with SE and to propose a treatment protocol for managing this combined presentation. We describe a case series of three patients who were diagnosed with SE and osteomyelitis affecting the same anatomical site. Diagnosis was based on clinical examination, imaging, and microbiological culture taken from the affected bone during the surgical excision of the exostosis.

Literature overview

The first description of SE dates to Dupuytren in 1847 [2]. Subsequent studies and literary reviews have highlighted its etiology, clinical presentation, and management [1, 2, 12, 13]. Being a relatively uncommon diagnosis, clinical reports about SE consist of case series and case reports [1, 2, 14].

The most recent systematic review from 2014 on SE of the toes sought out to review the best treatment approaches, the demographics, and common presentations of SE, and the complications arising from treatment [1]. The total number of reported cases of SE was 287, out of which only 124 cases examined treatment complications. They found the most prevalent complication to be onychodystrophy (16,1%). Of other complications, they described recurrence (4%), postoperative surgical site infection (3,2%), and chronic regional pain syndrome (0,8%).

A more recent literary review from 2022 described 500 cases of SE in the English literature, with 84,4% occurring in the lower extremity, and 15,6% in the upper extremity [14]. While this review highlighted onycholysis and recurrence as common complications, it did not mention osteomyelitis as a coexisting or complicating condition [14].

To identify previous cases of SE and concurrent osteomyelitis, a PubMed literature search was conducted on 19 January 2025 using the terms “SE” and “osteomyelitis” as free-text terms and MeSH-terms (Table 1). The search yielded 40 results, which were reviewed by title and abstract. None of the identified articles described SE with simultaneous osteomyelitis. Thus, to our awareness, this association has not been previously reported in the literature.

| Searchstring . | Results . |

|---|---|

| Search: (((exostoses) OR (exostoses[MeSH Terms])) OR ((“Subungual exosto*”) OR (Subungual exostoses[MeSH Terms]))) AND ((osteomyelitis) OR (osteomyelitis[MeSH Terms]))Sort by: Publication Date | 40 |

| Searchstring . | Results . |

|---|---|

| Search: (((exostoses) OR (exostoses[MeSH Terms])) OR ((“Subungual exosto*”) OR (Subungual exostoses[MeSH Terms]))) AND ((osteomyelitis) OR (osteomyelitis[MeSH Terms]))Sort by: Publication Date | 40 |

| Searchstring . | Results . |

|---|---|

| Search: (((exostoses) OR (exostoses[MeSH Terms])) OR ((“Subungual exosto*”) OR (Subungual exostoses[MeSH Terms]))) AND ((osteomyelitis) OR (osteomyelitis[MeSH Terms]))Sort by: Publication Date | 40 |

| Searchstring . | Results . |

|---|---|

| Search: (((exostoses) OR (exostoses[MeSH Terms])) OR ((“Subungual exosto*”) OR (Subungual exostoses[MeSH Terms]))) AND ((osteomyelitis) OR (osteomyelitis[MeSH Terms]))Sort by: Publication Date | 40 |

Case series

Patients and diagnostic workup

This case series includes three adolescents (two males, one female; ages 12–15) who presented with SE complicated by osteomyelitis between November and December 2024. All had a history of toe trauma followed by prolonged nail-bed abnormalities before diagnosis. Clinical examination and imaging, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and radiographs, confirmed the presence of SE and raised suspicion of osteomyelitis in all cases. Oral consent for publication of anonymized details was obtained from patients and their legal guardians.

Surgical management

Surgical excision was carried out within 1–3 days of diagnosis. Procedures included removal of the exostosis with thorough debridement of infected bone, during which five bone biopsies were taken for microbiological culture and microscopy. Intramedullary CERAMENT® G (BONESUPPORT AB, Lund, Sweden), a bone void filler containing gentamicin, was applied. The skin was closed with nylon sutures, and the nail was repositioned to preserve the natural nail bed structure.

Antibiotic therapy

Empirical postoperative antibiotics were initiated with intravenous benzylpenicillin (2 million units four times daily) and cloxacillin (1 g four times daily) for 1 week. Regimens were adjusted according to culture sensitivity in consultation with microbiology specialists. After 1 week of intravenous treatment, patients transitioned to oral antibiotics for an additional 5 weeks, completing a 6-week course.

Outcomes

All patients were discharged after 1 week. They were followed in the outpatient clinic at 2–3 weeks (for suture removal) and at 6 weeks post-surgery. Outcomes included absence of pain, resolution of infection, and no signs of recurrence.

Case summaries

Case 1

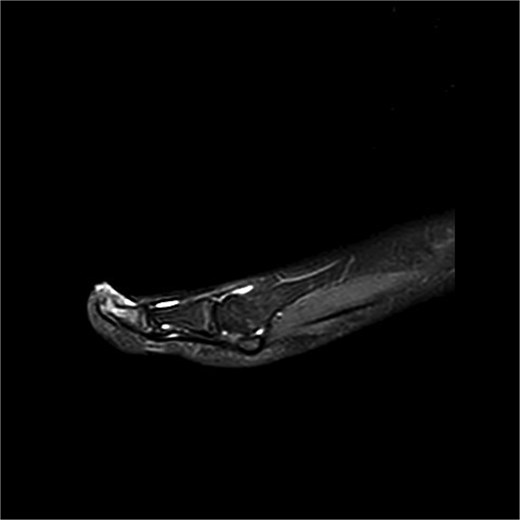

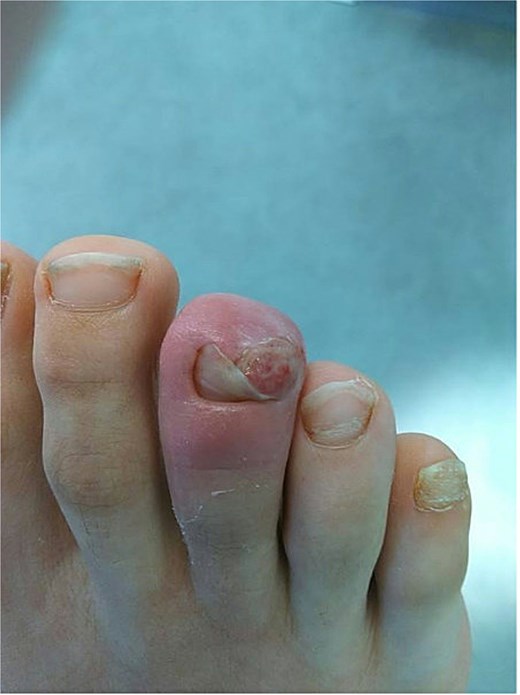

A 12-year-old male presented with pain and deformity of the right great toe (Fig. 1). MRI confirmed SE with osteomyelitis (Fig. 3). Bone cultures grew S. aureus and Staphylococcus lugdunensis with moderate growth in one of five samples. After 1 week of intravenous therapy, treatment was completed with oral dicloxacillin. At 17- and 39-day follow-up visits, the patient was pain-free with no signs of infection (Fig. 2).

Clinical photograph of case 1 showing the subungual exostosis lesion prior to surgical treatment.

Postoperative image of the affected toe in case 1, following surgical excision and debridement.

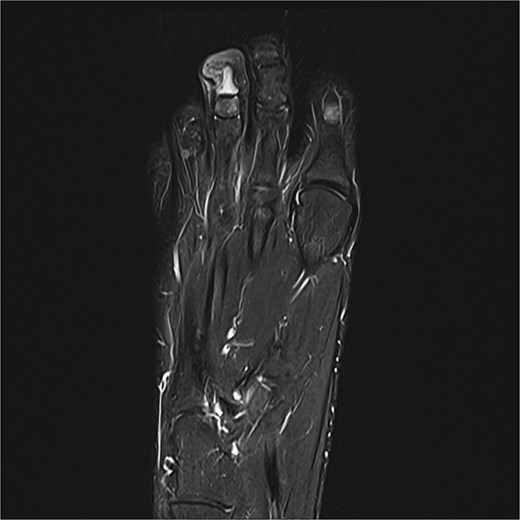

Preoperative MRI from case 1 demonstrating SE and associated bone marrow edema.

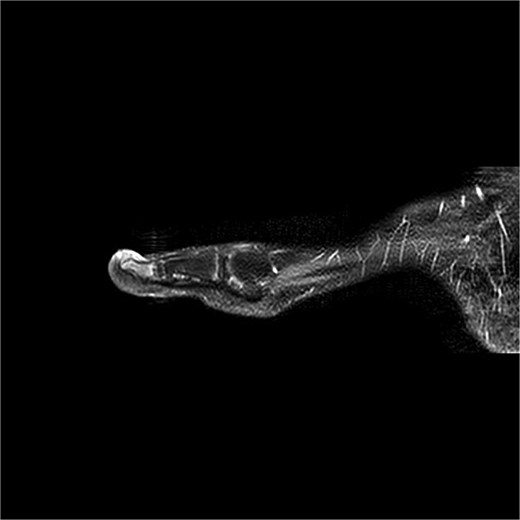

Case 2

A 14-year-old female presented with recurrent SE of the right great toe (Fig. 4). She had a history of osteomyelitis in the same location, treated successfully before SE developed. MRI confirmed recurrence with underlying osteomyelitis (Fig. 6). Surgery was performed 2 days later (Fig. 5). Bone cultures revealed Staphylococcus sciuri, Staphylococcus caprae, and Staphylococcus warneri, with sparse growth in all five samples. She transitioned to oral dicloxacillin after 1 week of intravenous therapy. At 16 days, she was asymptomatic, and a 3-month follow-up was scheduled.

Clinical photograph of case 2 showing the SE lesion prior to surgical treatment.

Postoperative image of the affected toe in case 2, following SE and debridement.

Preoperative MRI from case 2 demonstrating SE and associated bone marrow edema.

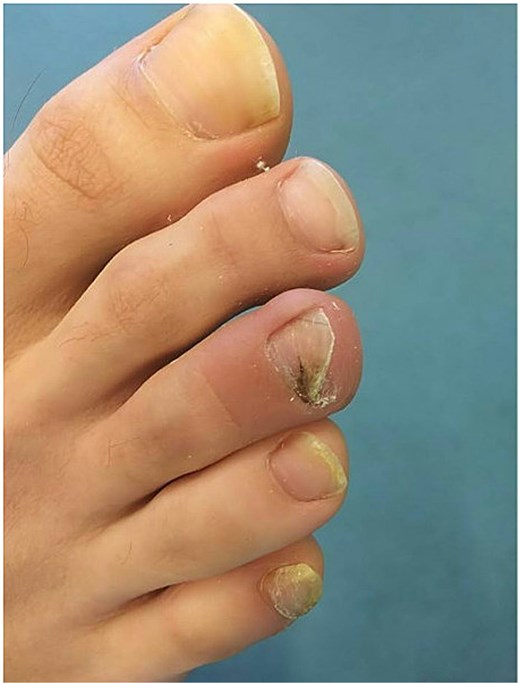

Case 3

A 15-year-old male presented with swelling and pain of the right third toe (Fig. 7). MRI confirmed SE with concurrent osteomyelitis (Fig. 9). Bone cultures identified Corynebacterium species, Staphylococcus simulans, S. lugdunensis, and Peptoniphilus species. After initial intravenous therapy, antibiotics were tailored to dicloxacillin and amoxicillin. At 14 and 35 days, the patient was asymptomatic and infection-free (Fig. 8). A 1-year follow-up plan was established.

Clinical photograph of case 3 showing the SE lesion prior to surgical treatment.

3 weeks postoperative image of the affected toe in case 3, following SE and debridement.

Preoperative MRI from case 3 demonstrating SE and associated bone marrow edema.

Discussion

SE, although benign, can cause significant pain and deformity if not promptly diagnosed and treated, both regarding the exostosis and osteomyelitis. Our cases demonstrate that osteomyelitis may develop as a direct consequence of the chronic irritation, bone exposure, microtrauma, or low-grade infection associated with SE. Radiographic imaging is pivotal in diagnosing osteomyelitis in otherwise clinical SE lesions, with MRI being the golden standard. Intraoperative bone cultures provide essential confirmation of osteomyelitis and identify the bacterial species involved, along with their antibiotic sensitivity.

Early recognition and treatment with targeted antibiotics, alongside surgical debridement when necessary, are key to achieving favorable outcomes. Since five intraoperative bone cultures are taken routinely in our department, we were able to detect the presence of osteomyelitis in concurrence with SE and initiate treatment.

The key finding in our case series is the presence of osteomyelitis within SE lesions— a combination not previously described in the literature on SE. This underscores the importance of considering osteomyelitis in SE cases. Our treatment approach resulted in symptom resolution in all cases.

Limitations include the retrospective design, small sample size, single-center setting, and relatively short follow-up. Longer-term studies are warranted to assess recurrence rates and functional outcomes.

Conclusion

This case series highlights a novel association between SE and osteomyelitis. MRI should be considered in all SE cases to evaluate for underlying bone infection. Intraoperative bone cultures are essential for confirming osteomyelitis and guiding targeted antibiotic therapy. Surgical excision combined with debridement, local antibiotic, and a 6-week systemic regimen resulted in infection resolution and no recurrence in all cases.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Herlev Hospital, for their support in the management of these cases.

Author contributions

Julia Haugaard, MD; Andreas Jørgensen, MD: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Original Draft.

Julia Haugaard, MD; Andreas Jørgensen, MD; Hans Gottlieb, MD PhD: Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Visualization.

Julia Haugaard, MD; Andreas Jørgensen, MD: Investigation, Resources, Project Administration.

Julia Haugaard, MD; Andreas Jørgensen, MD; Karen Dyreborg, MD PhD; Hans Gottlieb, MD PhD: Writing—Review & Editing, Validation, Supervision.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No external funding was received for this study.