-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Soukayna Bourabaa, Francesca Venza, Vito Laterza, The duodenum caught in a vise: a case report of high obstruction due to vascular compression, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 11, November 2025, rjaf952, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf952

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Obstruction of the duodenum by an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) has been rarely reported. It presents with symptoms of upper gastrointestinal tract obstruction. We report the case of an 81-year-old male with a history of infrarenal AAA previously treated by endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR). Computed tomography imaging revealed compression of the third portion of the duodenum by an aneurysmal sac measuring 9 cm, leading to luminal obstruction. A nasogastric tube was placed, allowing for decompression and resolution of the obstructive episode. Aortoduodenal syndrome is a rare cause of intestinal obstruction, with fewer than 40 cases reported. Surgical intervention is indicated in all patients except those who are too debilitated to withstand any intervention. Before the advent of aortic surgery, therapy consisted primarily of palliative gastric bypass. Resection of the aneurysm and graft replacement is the procedure of choice.

Introduction

Aortoduodenal syndrome is a rare clinical entity with fewer than 40 cases described in the literature [1]. First described by William Osler in 1905 [2], it classically presents as an upper GI obstruction and is characterized by stretching of the third part of the duodenum (D3) adjacent to an underlying AAA.

The clinical presentation includes nonspecific symptoms such as early satiety, postprandial vomiting, abdominal pain, and weight loss. Due to its rarity, it is frequently misdiagnosed or identified late. Diagnosis relies on imaging, particularly contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT). Treatment typically involves relieving the mechanical compression through aneurysm repair and GI decompression.

Case presentation

An 81-year-old man presented to the emergency department with signs of duodenal outlet obstruction, secondary to external compression from an enlarging aortic sac, which had developed following a prior EVAR. His medical history was notable for hypertension; chronic kidney disease with a solitary functioning kidney (estimated glomerular filtration rate of 22 ml/min/1.73 m2); peripheral arterial disease treated with iliofemoral endarterectomy followed by a femoral bypass for stenosis; and a history of bladder cancer previously managed with enterocystoplasty. Seven years earlier, he had undergone elective EVAR for an infrarenal AAA. Postoperatively, the aneurysm sac was monitored and found to have gradually expanded from 5 cm in 2015 to 8 cm in 2024, despite the absence of any endoleak on serial multiphase imaging, including contrast-enhanced duplex ultrasound (US).

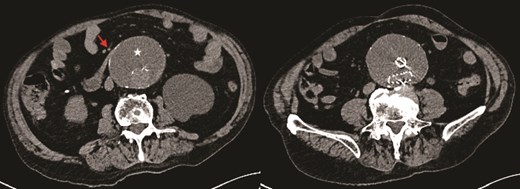

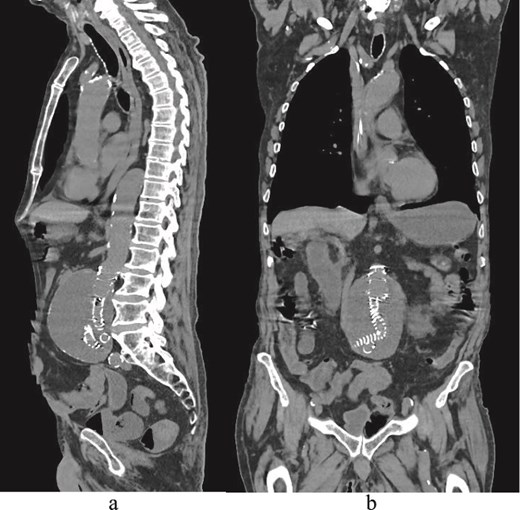

He presented with acute-onset abdominal pain, profuse vomiting, and diarrhea that began 1 day prior to admission. A contrast-enhanced CT scan revealed duodenal obstruction due to extrinsic compression by the aneurysmal sac, now measuring 9 cm in anteroposterior diameter, particularly at the level of the third portion of the duodenum (Figs 1 and 2). There was no evidence of endoleak. Incidentally, the scan also identified a suspicious rectal lesion. Laboratory investigations showed acute-on-chronic kidney injury with significant electrolyte disturbances. Initial management included nasogastric decompression, which yielded 3000 ml of gastric contents, along with fluid resuscitation, correction of metabolic derangements, and initiation of total parenteral nutrition. A multidisciplinary discussion was held involving vascular, general, and upper GI surgical teams. Surgical options, including a gastrojejunostomy to relieve the obstruction, were discussed in detail with the patient. After thorough deliberation, the patient declined any surgical intervention and opted for exclusive palliative care. He also refused further investigation of the rectal lesion. The clinical course was notable for symptomatic improvement within 48 hours, allowing for the gradual reintroduction of oral intake. The patient was subsequently discharged to a peripheral rehabilitation facility for continued supportive care.

Axial CT image demonstrating obstruction of the duodenum at D3 between the aortic sac (star) and superior mesenteric artery (SMA) (arrow).

(a) Sagittal delayed multiphase CT image showing no endoleak. (b) Coronal CT image demonstrating EVAR and an aortic sac.

Discussion

Aortoduodenal syndrome represents a rare but clinically significant cause of duodenal obstruction, typically resulting from extrinsic compression of D3 by an AAA. Unlike superior mesenteric artery (SMA) syndrome, which generally affects young, underweight individuals, this condition primarily occurs in older adults, with a clear male predominance. Although initially described over a century ago, only a limited number of cases have been reported in the literature.

A comprehensive review by Taylor et al. [3] identified 25 published cases between 1905 and 2016, noting an average patient age of 72.3 years and a mean aneurysm size of 7.4 cm. Interestingly, despite the large size of many aneurysms, only a minority of patients develop obstructive symptoms, suggesting that additional anatomical or functional factors are likely involved. The exact pathophysiological mechanism remains incompletely understood. The prevailing hypothesis involves direct compression of the retroperitoneally fixed duodenum between a distended aneurysm and the overlying SMA [4, 5], similar to the mechanism observed in SMA syndrome [6]. Additional factors such as duodenal adhesion to the aneurysm wall, changes in the duodenal axis, reduced GI motility (e.g. post-vagotomy), or congenital anomalies like intestinal malrotation have also been implicated in isolated cases [7, 8].

Clinically, the syndrome often presents with nonspecific but severe symptoms including persistent vomiting, weight loss, abdominal pain, and signs of gastric outlet obstruction. In one review, vomiting was the most frequently reported symptom (92%), followed by a palpable pulsatile mass (71%) and electrolyte imbalances (46%) [9]. These complications, especially when prolonged, can lead to aspiration pneumonia, renal impairment, and significant metabolic derangements, contributing to the overall morbidity [10].

The initial approach to management is typically conservative and supportive. Gastric decompression with a nasogastric tube, correction of fluid and electrolyte imbalances, and nutritional support are essential first steps. Imaging, preferably with CT or contrast-enhanced upper GI studies, should be undertaken to confirm the diagnosis and exclude alternative etiologies [10, 11]. Historically, surgical bypass procedures such as gastrojejunostomy or duodenojejunostomy were performed, especially prior to the widespread adoption of aneurysm repair techniques. However, these procedures were associated with variable outcomes and higher complication rates [10]. Currently, definitive treatment involves repair of the underlying AAA. Open repair remains the gold standard in fit surgical candidates and is associated with high rates of symptom resolution [10]. Since the 1980s, a series of successful outcomes following open AAA repair has been reported, with significantly reduced mortality. EVAR has emerged as a viable alternative, particularly in high-risk patients. Several case reports have documented successful resolution of symptoms following EVAR, even in patients with smaller aneurysms [12]. However, the effectiveness of EVAR may depend on aneurysm morphology and the extent of duodenal compression. In cases where EVAR fails to relieve obstruction, possibly due to insufficient sac shrinkage or persistent mass effect, conversion to open repair, or graft explantation may be required.

Other scenarios may necessitate individualized interventions. For example, in the presence of prior EVAR, bypass procedures such as gastrojejunostomy have been utilized to relieve obstruction [13]. In selected cases, a conservative approach may be more appropriate, particularly in malnourished or frail patients, where the risks of surgery outweigh potential benefits [14]. The long-term role of EVAR in managing aortoduodenal syndrome remains unclear, particularly regarding the timeline for sac regression and relief of compression. More data are needed to assess how aneurysm type (saccular vs. fusiform) and anatomical configuration influence clinical outcomes.

Conclusion

Aortoduodenal syndrome is an uncommon but clinically significant condition that should be recognized as distinct from SMA syndrome. It predominantly affects elderly patients and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of gastric outlet obstruction when an AAA is present. The high morbidity associated with this syndrome often stems from secondary complications such as aspiration pneumonia, acute kidney injury, and profound metabolic derangements. Prompt diagnosis and coordinated multidisciplinary intervention are crucial to reducing morbidity and optimizing clinical outcomes.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

No data were used for the research described in the article.

Ethical approval

All the data of this study were taken from the medical records of the patient. This report does not contain any personal information that could lead to the identification of the patient. Therefore, it is exempted from ethical approval.

Patient consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s legal guardian for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

References

- abdominal aortic aneurysm

- aortic aneurysm

- computed tomography

- aneurysm

- repair of aneurysm

- gastric bypass

- intestinal obstruction

- surgical procedures, operative

- tissue transplants

- diagnostic imaging

- duodenum

- palliative care

- phenobarbital

- nasogastric tube

- aortic surgery

- evar trial

- upper gastrointestinal tract

- compression

- vascular compression