-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Adnan H AlRashed, Abdullah M AlKhars, Mohammed N Alsaeed, Abdullah F AlKhars, Mohammed S AlArbash, Lina A AlMudayris, A rare case of missed locked posterior shoulder fracture dislocation, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 11, November 2025, rjaf881, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf881

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Posterior shoulder fracture-dislocation is a rare and often misdiagnosed injury leading to locked chronic dislocation and complicated management. Surgical management options vary based on chronicity, defect size, and patient-specific factors, with the modified McLaughlin procedure being a joint-preserving option for younger patients with large defects. We present a case of a 31-year-old male who had a missed locked posterior shoulder fracture-dislocation with a large reverse Hill-Sachs lesion, healed non-displaced proximal humerus fractures for >10 months following an electrical shock and fall. The patient underwent an open reduction and a modified McLaughlin procedure with lesser tuberosity transfer, resulting in significant symptom improvement and restored range of motion. Despite the often delayed diagnosis of posterior shoulder fracture dislocation, joint-preserving surgery such as modified McLaughlin procedure can restore function and improve quality of life in young patients with chronic injuries.

Introduction

Posterior shoulder dislocation is rare, accounting for only 3%–5% of all shoulder dislocations, with fracture involvement in about 1% of cases and an annual incidence of 0.6 per 100 000. Up to 60% of these injuries may be initially missed [1–4]. Posterior shoulder fracture-dislocations (PSFDs) diagnosed after 3 weeks are termed “neglected” or “locked,” and those neglected for >3 weeks are considered “chronic” [3, 4]. Clinically, patients present with a locked, internally rotated shoulder and an inability to externally rotate or elevate the arm [1].

The treatment goal is to restore shoulder stability and function by re-establishing the humeral head’s normal sphericity [5, 6]. Management depends on the duration of dislocation, extent of humeral head and articular surface damage, glenoid condition, and patient health status [1, 6, 7]. McLaughlin originally described transferring the subscapularis tendon into the humeral head defect to prevent recurrent instability [7]. Hughes and Neer later modified this by transferring the lesser tuberosity with its attached subscapularis into defects involving 20%–40% of the articular surface [8]. This modified technique is widely recommended for posterior impaction injuries. Several authors advise lesser tuberosity transfer if the dislocation is <6 months old and the humeral head defect involves 20%–45% of the articular surface [4].

Case presentation

A 31-year-old male with sickle cell disease presented to the emergency department after an electrical shock caused him to fall onto the back of his shoulder. He developed severe pain and inability to use his arm. Examination revealed the shoulder in adduction and internal rotation with marked limitation of flexion and external rotation. X-rays showed posterior shoulder dislocation with a non-displaced proximal humerus fracture (Fig. 1). The injury was overlooked, and he was discharged in an arm sling.

For 4 months, he was followed in fracture clinic as case of proximal humerus fracture despite a locked shoulder, and he was discharged. Ten months later, he consulted an upper extremity consultant for persistent pain, stiffness, and functional limitations affecting daily life and work.

Examination confirmed restricted range of motion (80° forward flexion, 0° external rotation, 70° abduction), the arm was in an adducted and internally rotated position.

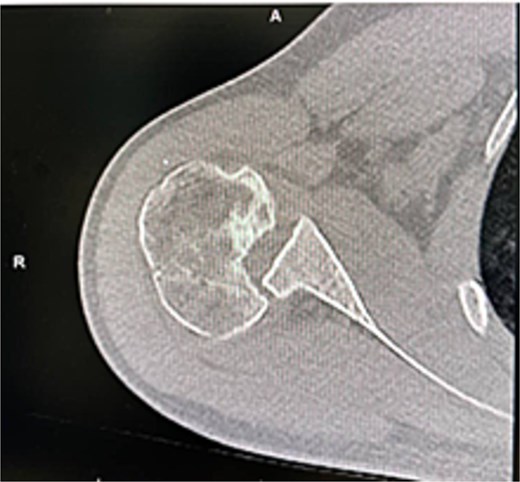

X-rays and CT confirmed missed locked posterior dislocation with healed comminuted fracture and large reverse Hill-Sachs lesion. MRI revealed posterior shoulder dislocation, reverse Hill-Sach’s lesion (Fig. 2) around 2.5 cm in diameter and 1.7 cm in depth, posterior labral tear, and secondary avascular necrosis.

He was counseled for open reduction and modified McLaughlin procedure. Through a deltopectoral approach, open reduction was achieved, and subscapularis with lesser tuberosity was transferred to the defect and fixed with a partially threaded screw. Postoperative X-rays showed satisfactory reduction (Fig. 3). He was discharged the next day in an external rotation brace.

At 2 weeks, the wound healed well, and rehabilitation began at 4 weeks. At 6 weeks, he achieved 120° forward flexion, 160° abduction, and improved external rotation. At 2 months, flexion increased to 140°, abduction to 170°. By 6 months, he reached 160° flexion, 170° abduction, with minimal external/internal rotation lag (Figs 4–6).

At final follow-up, the patient reported complete pain relief, improved range of motion, return to work, and marked improvement in quality of life, ending a year-long disability. This case is reported according to SCARE 2020 guidelines.

Discussion

PSFD is often difficult to diagnose at first presentation, increasing the risk of missed or delayed recognition, as occurred in this case. The typical injury mechanism involves forceful muscle contractions, such as during seizures, or high-energy trauma from falls or motor vehicle accidents [5, 9]. These forces can lock the humeral head in a posteriorly dislocated position, frequently causing an anteromedial impaction fracture known as a reverse Hill-Sachs lesion [5, 9, 10].

In our patient, the injury was misdiagnosed as an isolated proximal humerus fracture despite a locked shoulder, underscoring the importance of thorough examination and appropriate imaging to avoid overlooking this injury [1, 11, 12]. Presentation 10 months post-injury classified the condition as a chronic, neglected PSFD [3, 4]. Such delays limit treatment options and may worsen outcomes.

Management depends on chronicity, defect size, and patient factors [4]. Nonoperative management may be appropriate for older, low-demand patients [7], but in this young, active patient with a large reverse Hill-Sachs lesion (>45%–50% involvement) and chronicity, surgical intervention was indicated [9, 10].

The modified McLaughlin procedure—transferring the subscapularis tendon and lesser tuberosity into the defect—was selected to restore stability and preserve the native joint [7]. Although arthroplasty can be considered for chronic cases, particularly with major deformity or arthritis, it is generally reserved for older patients or when reconstruction is not viable [11, 12]. Making the modified McLaughlin procedure a reasonable choice for this young, active patient despite the delay [12, 13]. The presence of avascular necrosis complicated decision-making but did not preclude reconstruction, given the patient’s age and functional needs. Literature, including Kandeel’s work, supports reconstructive strategies such as lesser tuberosity transfer or bone grafting for similar cases [6, 14].

Postoperatively, the patient demonstrated marked improvement, with near-normal forward flexion and abduction by 6 months, minimal residual rotation lag, and significant pain relief. While chronic cases often achieve less optimal results than acute repairs, functional improvement and joint stability are attainable with appropriate surgical care [15].

This case illustrates the critical importance of early diagnosis through careful clinical and radiologic evaluation. However, it also demonstrates that even in neglected PSFD, tailored reconstructive surgery—such as the modified McLaughlin procedure—can deliver satisfactory functional outcomes, restore quality of life, and enable return to work in young, active patients.

Conclusion

PSFDs are rare and often misdiagnosed, requiring meticulous clinical and radiographic assessment. Delayed diagnosis complicates management, yet with precise surgical planning, good outcomes remain achievable. In this young patient with chronic injury and significant humeral head defect, the modified McLaughlin procedure offered a joint-preserving solution, restoring function and alleviating pain. While early detection is vital to prevent complications, this case highlights that even neglected injuries can achieve satisfactory recovery and improved quality of life with tailored reconstructive surgery.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to acknowledge the patient for his cooperation through the data collection and for his acceptance of his case to be reported and participate in the knowledge spread. Also, there was no funding granted for conducting this study.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Funding

The authors declare that there was no funding granted for conducting this study.

Informed consent

The patient was provided with written informed consent to participate, and to publish this report with protected confidentiality, and was archived by the ethical committee board.

References

- shock from electric current

- dislocations

- range of motion

- shoulder dislocations

- shoulder fractures

- surgical procedures, operative

- shoulder region

- fracture dislocation

- humeral fractures, proximal

- lesser tuberosity of humerus

- quality improvement

- misdiagnosis

- reverse hill-sachs lesion

- transfer technique

- delayed diagnosis

- subscapularis tendon transfer